Catherine Mulligan photographed by Ben Taylor.

Catherine Mulligan on Teen Mom,Tragic Paintings, and Y2K Trends

It’s a few days before Catherine Mulligan is set to open her first solo show at Tara Downs gallery in Tribeca, and the artist—unlike the grotesquely candid subjects in her work—is feeling a little shy. Since finishing her MFA at Indiana University Bloomington in 2019, Mulligan has been quietly accumulating a fan base for her eerie oil paintings featuring hyper-feminine zombified women and abandoned buildings that embody both a refuge and refusal of Y2K-era cultural malaise. With her latest exhibit, Bad Girls Club, the Brooklyn-based painter is bringing her teenage traumas into the present with works that elicit a warped embrace of the algorithmically-induced beauty trends of the current era. To learn more, our senior editor met with Mulligan to preview her haunting new exhibition, and discuss early aughts reality television, Tan Mom, and turning tragic imagery into a tool for empowerment.

———

TAYLORE SCARABELLI: I’m going to start recording. Maybe we can start with the name of the show.

CATHERINE MULLIGAN: It’s called Bad Girls Club, it’s inspired by the reality show.

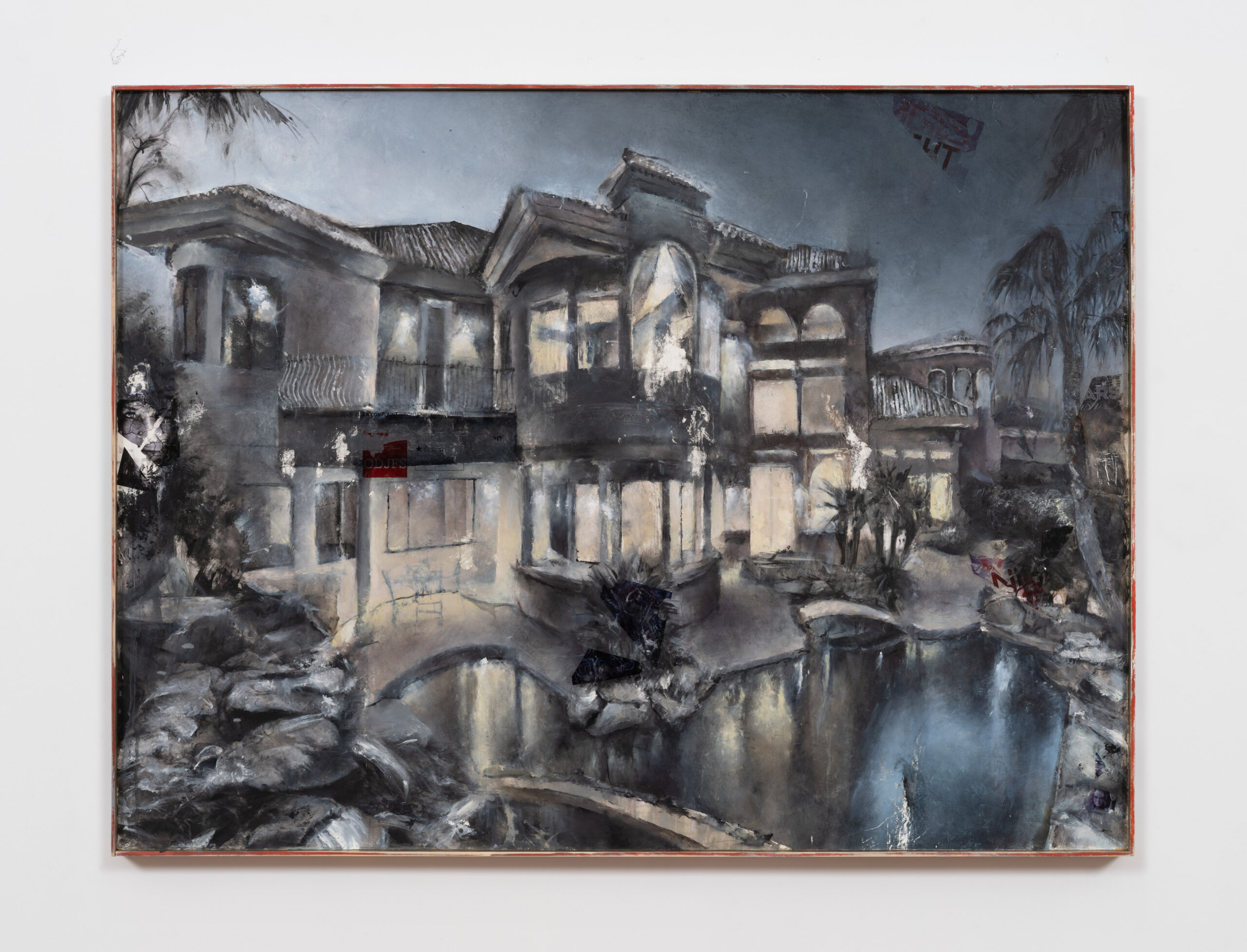

SCARABELLI: Is this the house?

MULLIGAN: It’s not.

SCARABELLI: It could be.

MULLIGAN: Right? I collect a lot of images. This is a mansion image from Zillow that I thought would work well as a painting because it kind of reads like an establishing shot.

Las Vegas Mansion, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist and Tara Downs, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella.

SCARABELLI: Where is this McMansion?

MULLIGAN: Vegas.

SCARABELLI: It’s spooky. It’s giving foreclosure vibes.

MULLIGAN: I kind of like things feeling like ruins, or like evidence or something.

SCARABELLI: I think you and I grew up around the same time. A lot of this feels like a reference to our teen years and what was going on culturally then. It’s almost like a postcard from the past or a warning to your younger self from that era. I really feel that with some of these women who are wearing all of these very youthful Y2K-era clothes, but they look like they’re 35 years old. There’s something really dark and sinister about that.

MULLIGAN: Yeah.I guess I was thinking of them as ghosts in a way. Once culture has disposed of people, where do they go? Like child stars, former reality stars. I’m obsessed with Farrah Abraham and that kind of—

SCARABELLI: Who’s Farrah Abraham?

MULLIGAN: She was on Teen Mom. But then she just went on to do a whole tour of reality shows. She also did Couples Therapy, but her partner never showed up.

SCARABELLI: That’s terrible.

MULLIGAN: There’s definitely a sense of tragedy around it.

Nouveau Riche, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist and Tara Downs, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella.

SCARABELLI: Where did you grow up?

MULLIGAN: North Jersey.

SCARABELLI: What was it like being a teen in Jersey in the early aughts? Were you a mall rat?

MULLIGAN: Not really. I was kind of a weirdo. But I feel like it totally influenced me. A lot of my work is about taste politics. My parents were very tasteful, educated people but where I grew up, you saw a lot of fake nails—Tan Mom is from my hometown. She had a child abuse case where she was putting her 5-year-old in a tanning booth.

SCARABELLI: Yikes.

MULLIGAN: There was this sort of vulgarity that I was always drawn to, but sort of suppressed.

SCARABELLI: So it’s a rebellion?

MULLIGAN: A little bit. I went to a really traditional school. I used to be a realist painter.

SCARABELLI: What shifted for you?

MULLIGAN: I think just my work didn’t match the weirdness of my experiences. In my early twenties, I was going out a lot and—

SCARABELLI: In New York?

MULLIGAN: In Philly, just trashy stuff. I was wearing going-out clothes and then getting black-out drunk. Something about that sensory experience was just—it had some kind of artistic potency to me. Hyper-femininity, drinking culture, and the dark side of all of it.

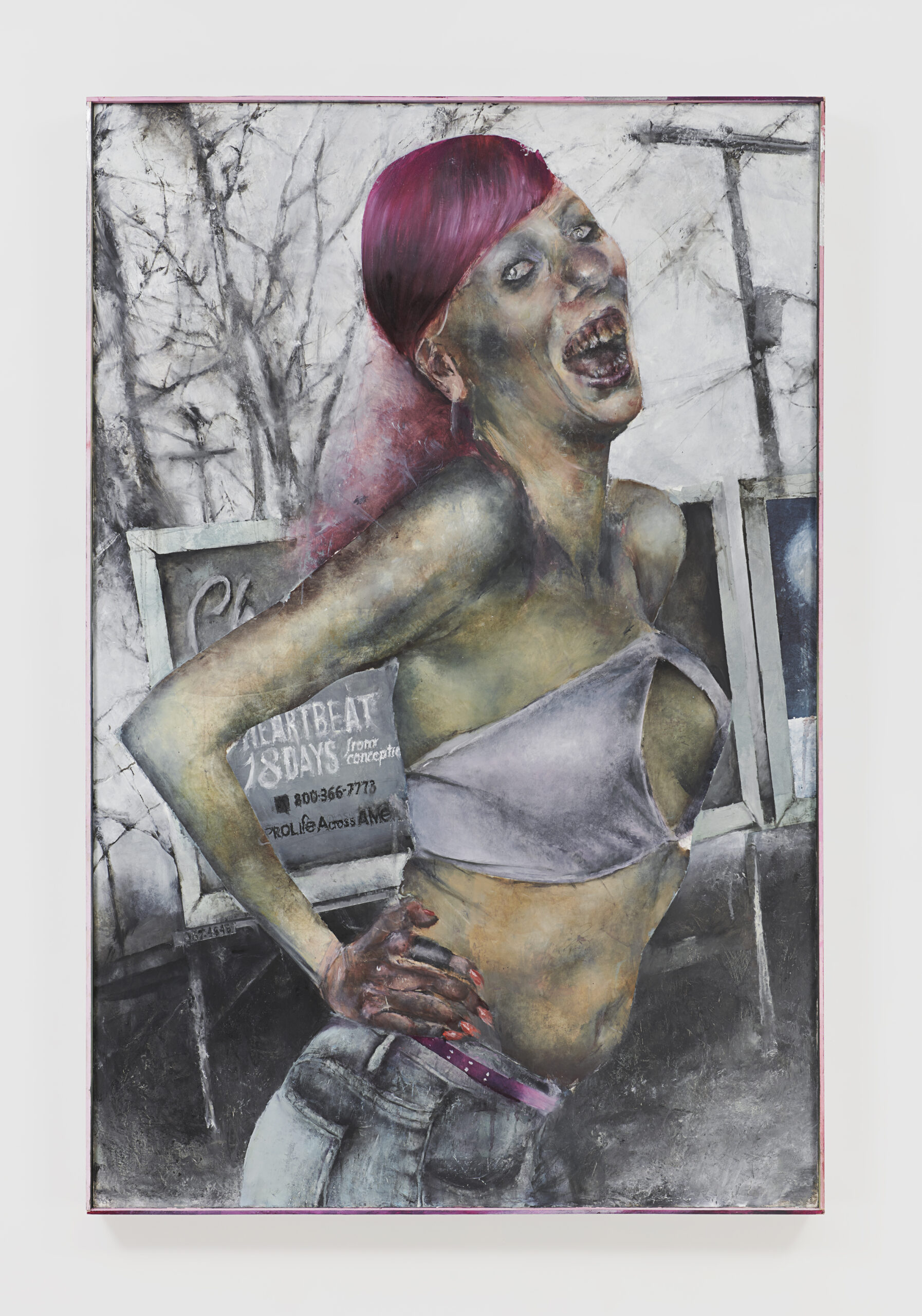

Hitchhiker, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist and Tara Downs, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella.

SCARABELLI: I can relate to that. Let’s keep walking. Okay, this one is horrifying. She’s fully a zombie. I really like her belly. What’s it called?

MULLIGAN: “Hitchhiker.”

SCARABELLI: Okay. It says, “Pro-life across America.” Is she pregnant?

MULLIGAN: No. I just wanted it to feel dystopian.

SCARABELLI: It’s all very Y2K and it’s triggering for me. Maybe that’s just because it’s the first time that an era that I lived through is being regurgitated and I’m like, “Oh my god, the kids are dressing how I dressed in high school.”

MULLIGAN: I can only see that through the lens of being a very alienated teenager. Those clothes were never going to look right on me, and I feel like there’s something in that aesthetic that’s just gross. It kind of contains that alienation.

SCARABELLI: Uh-huh.

MULLIGAN: It might be very subjective. But I feel like it’s this sort of abject space where things aren’t really vintage, they’re just recently discarded and they haven’t really been properly reappraised. But it’s weird because Y2K style was trending, and now it’s just this very tired thing.

SCARABELLI: But it’s not really. We think it’s tired because we’re in New York. But the reality is it’s brand new for someone else in the Midwest. Also these bulbous noses really freak me out. It’s kind of reminds me of an old man whose cartilage kept growing or whatever. [Laughs]

MULLIGAN: Yeah. I think that’s something that I’m self-conscious about, because I have this sort of bulbous nose. People have asked me, “Oh, is it based on you?”

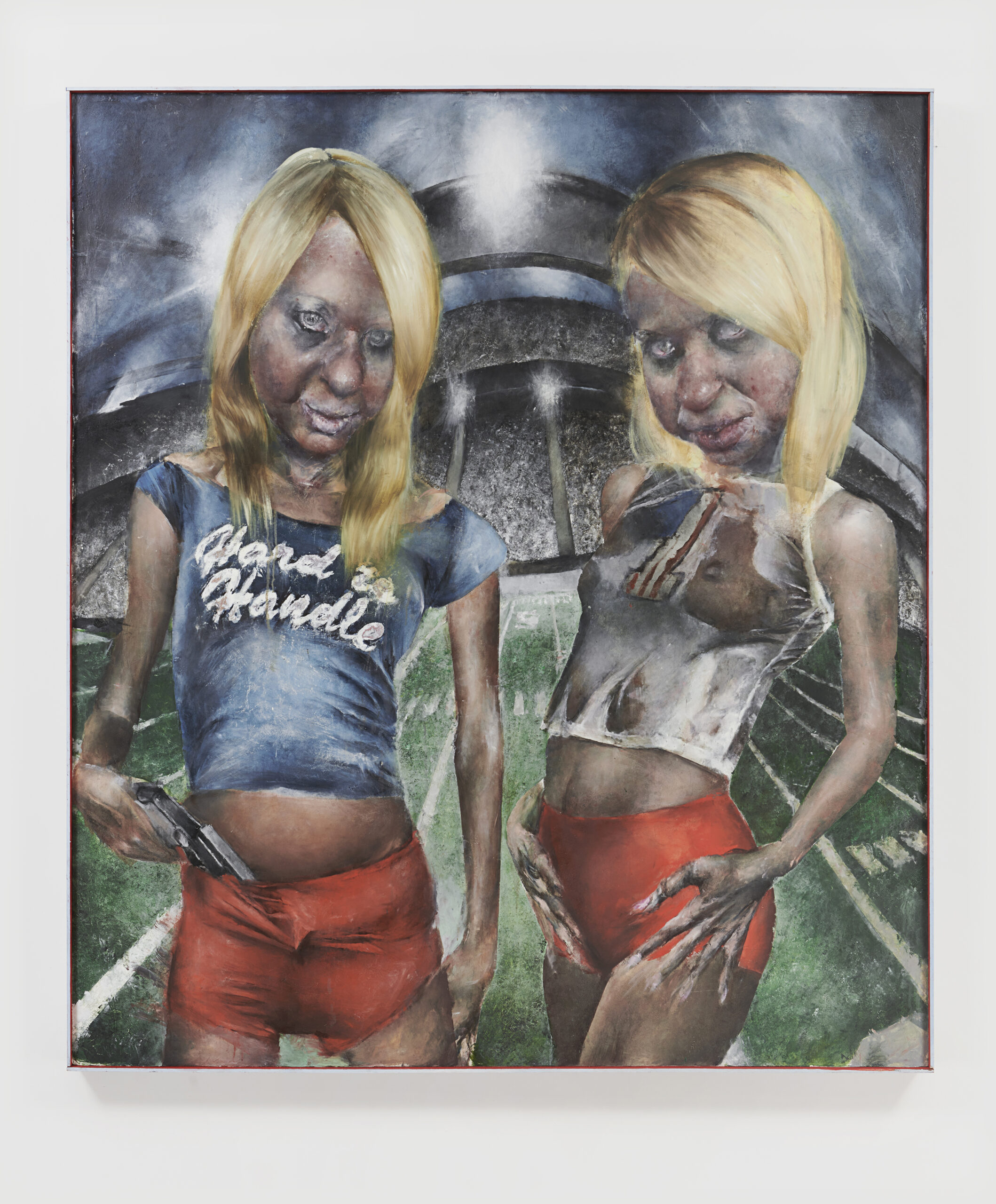

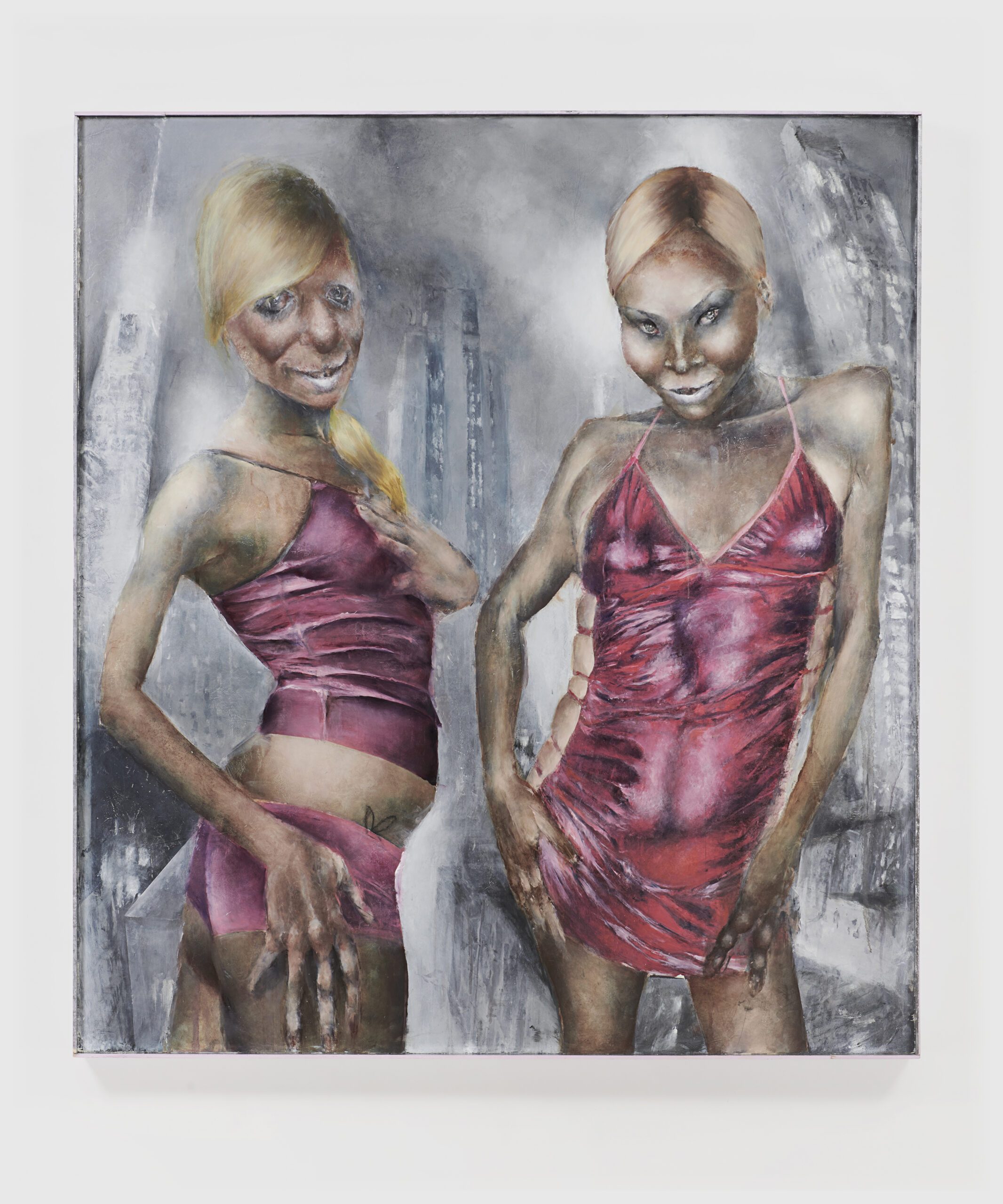

Sisters, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist and Tara Downs, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella.

SCARABELLI: Has anyone ever accused your work or you of being misogynistic? That’s happened to me with fiction writing, particularly when it’s more autobiographical.

MULLIGAN: People have commented when someone’s posted my work online, but I really don’t think it’s misogynistic. I don’t think the only way to be feminist is to make women look beautiful.

SCARABELLI: Right. But also, it’s art. It doesn’t need to be moralistic.

MULLIGAN: You have to let art surprise you, and you can’t get to that place if you’re self-censoring from the beginning.

SCARABELLI: But it is somewhat autobiographical?

MULLIGAN: To me, they are kind of feminist. They have agency. They’re staring at you. They’re threatening.

SCARABELLI: But part of what I get from this also is a bit of white guilt.

MULLIGAN: Maybe.

Sisters, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist and Tara Downs, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella.

SCARABELLI: There’s something about turning these over-the-top women who are asking for attention, taking up a lot of space, into these grotesque figures.

MULLIGAN: Or just trying to knock them down a peg. There is a dark side to womanhood.

SCARABELLI: I like how the bodies also don’t really make sense in some of them.

MULLIGAN: Yeah. They’re kind of pieced together and distorted. I have folders on iPhoto that are like, “Hair styles, body parts, clothing.”

SCARABELLI: Oh, yeah. I saw the mood board in the book that you’re publishing with the exhibition, we should pull that up. We have Donatella Versace. We’ve got a young Ariana Grande. What’s this?

MULLIGAN: That’s an Ivan Albright. He’s one of my favorite painters. That’s Grünewald who did those Christ paintings.

SCARABELLI: Wow.

MULLIGAN: So yeah, I guess the history of grotesque imagery sort of sometimes has a moral dimension or pathos.

SCARABELLI: Do you think your work is moralistic in that way?

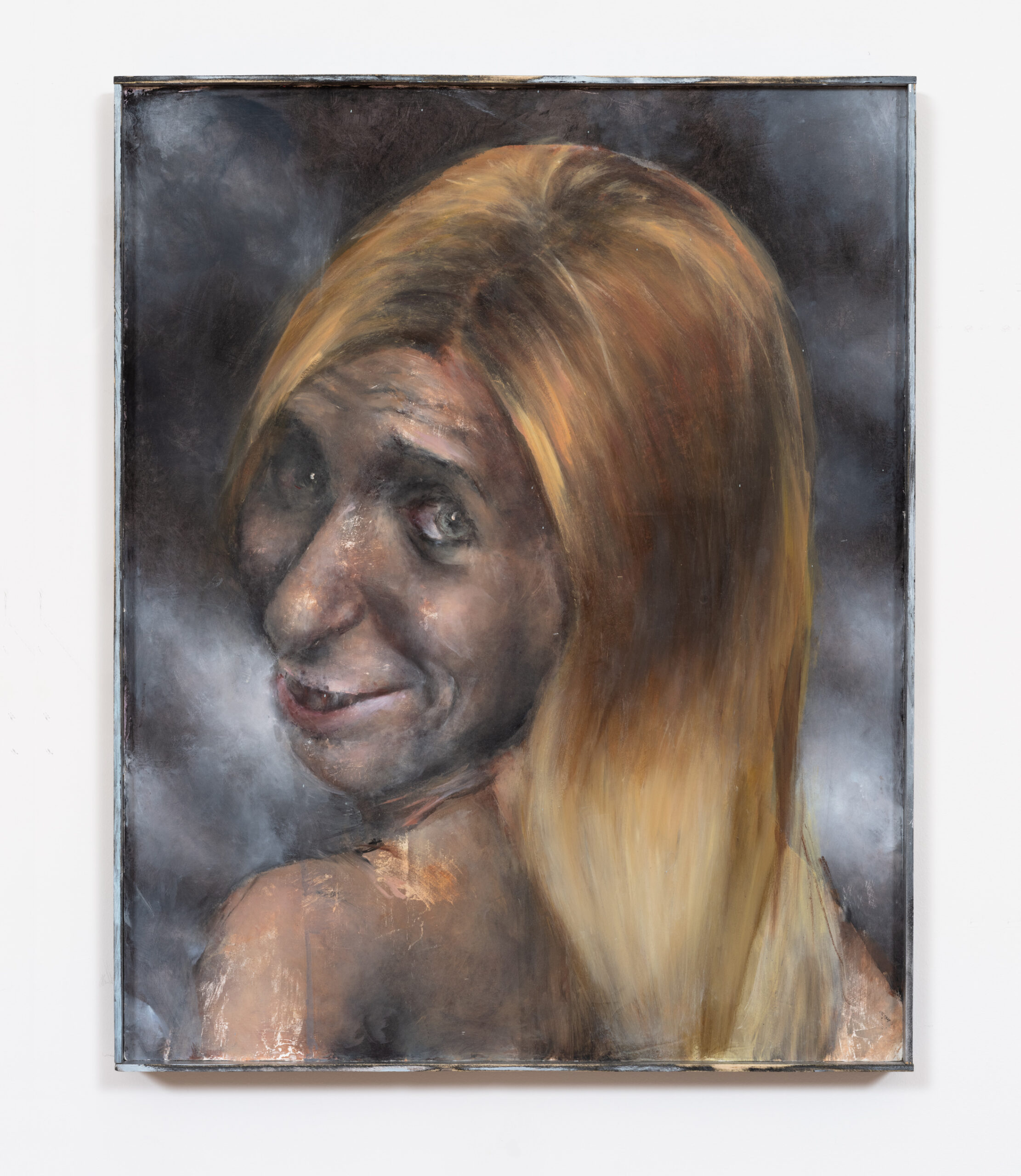

Nocturne 2, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist and Tara Downs, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella.

MULLIGAN: To me, it’s kind of cathartic actually. The uglier I make them—it’s like those Cindy Sherman pieces from the ’80s with the woman screaming in the glass. She was just really angry when she made those. And I think about that a lot. She didn’t use that anger to try to appease people. She used it to make the work uglier and uglier. And so I’m not attacking these women. I’m using these women to attack the viewer.

SCARABELLI: Mm-hmm.

MULLIGAN: I think about it like proxies. So there’s not really a moral dimension.

SCARABELLI: Oh my god, this one, this one is so tragic. This is what I see when I look in the mirror. It’s very relatable. It’s kind of like a twisted yearbook photo, with a bit of Exorcist vibes.

MULLIGAN: Yeah, and she’s in this indeterminate space.

SCARABELLI: It’s beautiful. There’s something interesting about how you’re putting all these different photos together. It reminds me of those weird AI-generated images. Like when you have a hot girl with three arms or whatever.

MULLIGAN: I think it’s always the hands that are the most bewitching part. In this one, her hands are like anal beads.

Clubbers 2, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist and Tara Downs, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella.

SCARABELLI: Did you ever see that show Bridalplasty?

MULLIGAN: No.

SCARABELLI: You should watch it. It was only one season, but it’s all these brides-to-be competing to win the ultimate plastic surgery makeover.

MULLIGAN: Oh, wow. It was kind of like The Swan?

SCARABELLI: Yeah, but it only lasted one season because it was so crazy and fucked up. What shows are you watching right now?

MULLIGAN: I’ve been watching Celebrity Big Brother on YouTube.

SCARABELLI: Who’s on it?

MULLIGAN: There’s a season with Pete Burns. I’m watching the one right after with the weirdest mix.

SCARABELLI: Has anything really crazy ever happened on Big Brother?

MULLIGAN: I feel like the biggest reality controversy was Megan Wants to Marry a Millionaire. A finalist killed somebody right after. It was a spinoff of Rock of Love.

SCARABELLI: Whoa. I believe that because the spinoff with Daisy de la Hoya was some of the darkest shit I’ve ever seen.

MULLIGAN: Daisy of Love?

SCARABELLI: Yeah. She seemed really fucked up on drugs and the men were all being so aggressive with her. I was like, “This is so insane that this was on TV. And also, what does it say about me that I’m watching it?”

MULLIGAN: Yeah.

SCARABELLI: That’s how your art also makes me feel, complicit in a celebration of dark humanity and Americana.

MULLIGAN: Thank you.

No comments:

Post a Comment