For Karl Ove Knausgård, it's all the small things

With his wildly popular autobiographical series My Struggle, the author breaks down the banal

Emily M. Keeler

October 24, 2014

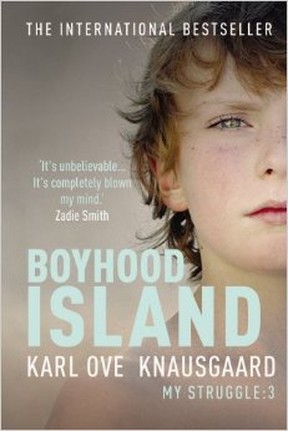

Title: Boyhood Island: My Struggle, Book 3

Events at International Festival of Authors:In Conversation with Karl Ove Knausgård, Oct. 25, 7:30 p.m., Fleck Dance Theatre, 207 Queens Quay West ($18);

Roundtable: Boys to Men, Oct. 26, 12p.m., Fleck Dance Theatre, 207 Queens Quay West, Toronto ($18)

“It doesn’t feel like a memoir to me, partly because it doesn’t reveal enough stories from my life,” Karl Ove Knausgård says over the phone. Considering how it clocks in at close to 4,000 pages in total, it’s hard to imagine that Knausgård has left anything out of My Struggle, his profoundly autobiographical novel that spans six volumes. “It’s much more like the process of a novel,” he says, “much more like an existential search for something.” Five years after the first book of the series was published in Scandinavia, Knausgård’s search continues.

My Struggle is a contradiction; the adjectives most frequently applied to the project are various synonyms for “boring” and “riveting.” My Struggle begins with a man, Knausgård, telling his reader that he had wished to create great art, but instead looks at his life as a middle-aged father and husband and sees nothing but endless laundry, meals to make, the quotidian drudgery that over time may or may not amount to a life. He travels back into his memory, to access some originating point and reconcile himself with the fact that a life is not lived in moments of greatness, but in the utterly banal tasks that fill our days. And when it comes to banality, Knausgård’s most singular virtue is that he has spared, essentially, nothing.

For example, there is a 70-page digression in the first book, ominously subtitled “A Death in the Family” for English-language readers, detailing the tumults and anxiety attendant to getting beer to a house party while underage. Young Karl Ove hides some beer in the New Year’s Eve snow, and his memory of navigating the quagmire of friendly parents and public transit in 1980s Oslo is an exercise in comprehensive recall. Not to spoil anything, but teen Karl Ove eventually ends up a little drunk. By way of contrast, consider how Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper and Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw are about 65 pages each.

Zadie Smith calls the series mind-blowing, and she finds the books so addictive she has compared them to crack. Jeffrey Eugenides told a reporter for The New Republic that Knausgård “broke the sound barrier of the autobiographical novel.” Rachel Cusk describes My Struggle as “perhaps the most significant literary enterprise of our times.” In The New Yorker, James Wood marvelled “even when I was bored, I was interested.” The accolades seem inconceivable when one steps back and looks to the text: a sprawling, often inelegant account of the details of a life. And I do mean details, the nittiest and grittiest.

I had a feeling of being surrounded by fiction. That fiction was dominating the way I looked upon my own life, the way I looked upon the world

Knausgård’s radical, comprehensive transparency on the narrative of his life puts him in a zeitgeisty cohort of authors invested in creating a kind of real-time, reality fiction. You could easily put My Struggle on the shelf beside Ben Lerner’s 10:04 or Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be?. Heti, in fact, will be interviewing Knausgård in Toronto this Saturday at the International Festival of Authors.

“When I started this project, I saw already a kind of movement happening in art, and in literature, about using your own biography, your own name, using your own life,” Knausgård says. The trend he’d identified initially made him doubt his impulse to write these books. “I thought I shouldn’t do it because it was so unoriginal, just because everybody was doing it,” he says. Not for the first time, he sounds a little bored with me, punctuating his thoughts with comically resigned sighs. “People do the same things,” he says, “go in the same direction, because we live the same lives in the same world. So.”

The pull to use his life in the service of making literature proved impossible to resist. The process of writing the books also proved to be, of course, a preoccupation of My Struggle. Frequent asides, metafictional overtures and aphorisms act as connective tissue, essays linking Knausgård’s story to the work of telling it. “That which is remembered accurately is never given to you to determine,” he explains in book three, on the instability of memory.

“I had a feeling of being surrounded by fiction. That fiction was dominating the way I looked upon my own life, the way I looked upon the world,” Knausgård says. “You know, I had images from television, images from newspapers and airwaves. I had fiction as a form of being; I was living my life through images. My own experience of my own direct experience of the world kind of disappeared. I felt inauthentic, in a way. And I wanted to try to write about that, and to try to write about life as it really was.”

‘I can’t think with that notion that everybody knows me. That I’ve given over everything. Because that’s not something you can live with’

Readers recognize themselves in Knausgård’s picture of life as it really is, in the everyday experiences of growing up. “The reactions of people are very personal,” he says. “They don’t really want to talk about the book. They want to talk about their own lives.” For all of the hyper-particular things — the specific sandwiches Knausgård ate in uncomfortable proximity to his brutish father are a descriptive fixture of the text throughout — a universal sensibility emerges; we find meaning in the trivia of our own stories. Reflecting back on seeing something strange in footage from the nightly news, Knausgård writes in book one about waiting up to witness his parent watch the late-night rebroadcast: “I just wanted to find out if they could see what I had seen.”

“When I wrote it, it was very private. It was only me, alone in a room,” Knausgård says. “And it has to be like that. If not, I couldn’t have written it.” My Struggle has sold nearly half a million copies in Norway, which means more than 10% of the country’s population has purchased it. Because of Knausgård’s commitment to total veracity, every member of his family, from his first cousins to his ex-wife, has been put under a national magnifying glass; Scandinavian journalists have attempted to interview almost everyone Knausgård has ever met. Because he depicts the deaths of his father and grandmother in a devastating, wintry light, the paternal side of Knausgård’s family have tried to stop the publication and translation of the series. They have severed all contact.

A smash hit in Scandinavia, My Struggle has gone on to be an international bestseller. Translated into 22 languages, the audience for Knausgård’s ruminations on a lunch he ate when he was a child, or his pre-adolescent observations on his own penis — “like a little cork. Or a kind of spring, because it quivered when you flicked it lightly” — continues to expand. It’s, understandably, a source of anxiety for the 45-year-old father of four. “I just deny the fact that people know everything about me. I deny it every day.

“I don’t really understand that when I see someone they might know anything about me,” Knausgård continues. “And I live in the countryside in Sweden, where they actually do not know anything about me.” Feeling overwhelmed by the attention paid to him in Oslo and Norway, Knausgård and his family have moved to a remote farm town in Sweden, hoping to live something like a normal life. The irony that providing a literary accounting of an ordinary life has vaulted him into extraordinary circumstances is something he talks about with a hushed awe. “I can’t think with that notion that everybody knows me. That I’ve given over everything. Because that’s not something you can live with.”

“When you write, art is a way of putting distance to notions of who you are,” Knausgård adds. He describes how he had never felt freer than when writing, or even reading. Literature, he says, is a place people go to escape the shameful episodes we call life. “I had to write about all the things I hate about myself, which I had tried to use literature to get away from, you know?”

And that was the starting point. Even after the frenzied response to My Struggle’s initial publication, after the family fallout and the gossip mills and relocation, Knausgård knew he couldn’t stop once the project was underway. “I thought I had to stay in this, I can’t escape this, even in writing. The strange thing was that literature still was liberating, that I still was free.”

No comments:

Post a Comment