Article content

Photographer Sally Mann puts her life in frame

"I still feel vulnerable and exposed, and I am even more mistrustful of our culture’s cult of celebrity," says the reclusive Virginia artist.

Emily M. Keeler

June 2, 2015

“I’m from the South,” Sally Mann says as she is handed a foamy cappuccino in a hotel cafe in Toronto on a recent afternoon. “I”m gonna need a lot of sugar.”

Her regional dialect, the warm drawl of Virginia farmland, is more than an accent; it shapes not only the sound but the very substance of her thinking. The South of the imagination exists as a kind of circular narrative — even for the people who live there, the place is a story.

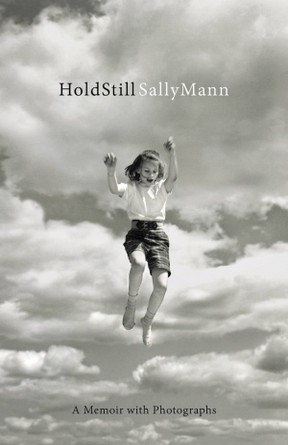

Mann was born in Virginia, where she still lives. Her stunning photographs often depict moments of radical vulnerability, like those collected in Proud Flesh, a series in which she tenderly documents the body of her husband, Larry Mann, who is afflicted by muscular dystrophy. She attributes the power of her images to the influence of the land she lives on; the farm where she’s raised her family occasions no small measure of lyricism in her new, sumptuous memoir, Hold Still.

The memoir sees Mann turning to prose to further the kind of work she’s been doing with her photographs; here she investigates family, lineage, history, and of course, the politically vexed beauty of where she’s from. Hold Still is an intimate inventory of the life Mann, who is now 64, has been documenting as a photographer since the 1970s.

Mann became a household name in the 1990s, with the publication of Immediate Family, a series of portraits of her children living out their private lives on the family’s secluded farm. In one iconic image, Mann’s pre-adolescent daughter, Jessie, holds a candy, her jaw set in an expression that fails to gel with a romantic image we hold of childish innocence. Instead, Jessie’s gaze fixes on the viewer, on the camera’s lens, with a sense of defiant authority; she sees you looking, and she’s looking right back.

Other images depict Mann’s children in various states of nudity. Dancing, swimming, feeling the sun on their skin. The New York Times Magazine profiled Mann at the time of Immediate Family’s publication, and depicted the artist’s work as potentially troubling for the unfettered way she depicted the sensuous abandon of childhood. “The Perfect Tomato” depicts a naked child dancing on her tippy-toes across a picnic table, her arms extending heavenward over a lunch spread of, what else, tomatoes.

At the time, Mann was assailed by hate mail, accusing her of, at best, being an inadvertent pornographer, and at worst, celebrating and promoting incest and sexual abuse. It was a dark time for the whole Mann family, when it seemed as though the world had been invited to their secluded farm. In Hold Still, Mann describes how the letter kept arriving throughout the past 25 years, finally seeming to stop in 2012, the year before she began writing her memoir: “Even now, writing this a year later, I still feel vulnerable and exposed, and I am even more mistrustful of our culture’s cult of celebrity.”

The chapter where she addresses the impact of the controversy on her life, including trips to Quantico to discuss them with the federal agents responsible for tracking the and stopping the distribution of child-pornography, accounts for 70 of the book’s 500 pages, but is the focal point of much of the press Mann has been doing on her publicity tour. The media, she says over her sugared coffee, have been “relentlessly badgering me about the family pictures.”

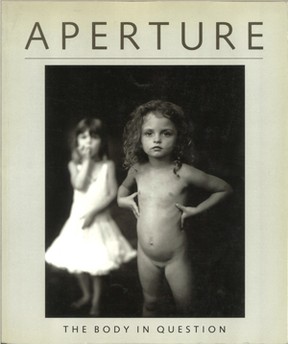

The controversy had lingering effects on her children — more so, it would seem, than the photographs themselves. Mann recounts a heartbreaking incident where her youngest child, Virginia, experiences bodily shame for the first time after seeing one of her mother’s images censored in a newspaper article. The photograph, Virginia at 4, depicts the young child standing naked before the camera, her eyes holding onto the lens as her hands rest in the spaces of her delineated ribs, her hair a halo of wild curls. The picture graced the cover of Aperture Magazine in 1990, and was printed, without permission, Mann notes, the following year in The Wall Street Journal, cropped into a kind of mug shot, with black bars over the child’s chest, vulva, and eyes. Seeing herself broken up like that, Virginia started wearing shorts and a shirt into the bath.

“It was a long time ago, 25 years ago,” Mann says. “And it just seems irrelevant now. We’re so far past it. The youngest child is 30 years old. Are we really talking about ‘Are the children okay?’ ” she sighs, frustrated by the questions of reporters and broadcasters have been asking her for 20 years. Not without a tingling sense of irony, I ask her if it’s difficult to relive that period of time now, on book tour. In the book, Mann expresses trepidation and regret over her previous dealings with journalists; she quotes from Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer, and we are both aware that neither of us is talking to the other without ulterior motivation. She says yes, it is difficult; she cites two radio appearances where she felt that period of her work was given undue intention.

Just before we met, Mann had been giving an interview to a local broadcaster. “Once they turn the microphones off,” she says, “ — whatever her name was, she said, ‘Look, I’m really sorry I had to ask you all these questions.’ And she said, ‘I don’t think it was the nudity that bothered all those people.’ And I said, ‘No, it wasn’t the nudity.’ It was that forthright, competent, direct look that those children gave the camera: full of agency. They seem preternaturally wise and sophisticated, and I think that’s what upset people as much as anything else.” It’s also what makes the photographs so stunning, breeching the intimacy of the family and elevating these images to art.

“There’s strength in their vulnerability,” Mann says, when I ask her what unites her subjects. “I feel I’m a strange mixture of insecurity and strength. Most of us, probably most people. I’m transferring that same concept to the people I photograph.” This fiery sensitivity, being so easily wounded but also so strong, industrious, and proud, is what unifies all of Mann’s work, including Holding Still. Mann writes insightfully about her ancestors, her friends, and her own work, but always in an inquisitive mode; through these disparate elements, she seems to be looking to understand herself. The work comes precisely from her own vulnerabilities, the tangled and arbitrary threads that tether each of us to what matters in this world.

Mann’s prose is gentler, and warmer than her photographs typically are — the large format pictures she’s been taking for most of her life tend, on the whole, to appear haunted, if only by the chilling effect of the camera. Some have a piercing clarity, where others, through the miracle of foggy exposures, have the hazy, otherworldly air of a good ghost story. Growing up on the land that produced William Faulkner and Eudora Welty, it’s no wonder she describes her work as lyrical, and possessed of a kind of humbling nostalgia. Pictures, she says, rob us of our memories. “I think, as instruments of memory, photographs are not very well-tuned.

“I try and take the commonplace — and some of it is writ large, like death — take the commonplace and make it universally resonant, revelatory, and beautiful at the same time,” she says about her photographic work. When I point out that that’s the goal of literature, too, she laughs. “I wasn’t a writer when I started,” she says, “I know I’m more dedicated now to taking pictures that are in service of a concept, and that might be partly because I’ve had to be so specific in my writing, and so clear in my concepts.”

Before writing the book, she says, “I was just taking pictures to see what they looked like. Just for the fun of it. It wasn’t about anything, in some cases. Some of them were just about the joy of opening up an aperture and seeing what shows up.”

No comments:

Post a Comment