Josef Koudelka: Next by Melissa Harris review – in praise of a wandering star

A visual biography of the restless and revered Czech photographer reveals his affinity with the Roma people and his eye for haunting, unforgiving landscapes

Sean O’Hagan

Tuesday 2 January 2024

In 2008, I spent a few days with Josef Koudelka in Prague, the city he had immortalised in photographs 40 years previously as Russian tanks rolled into its streets on the evening of 20 August 1968. He had only recently returned to his homeland, and was about to be belatedly honoured with an exhibition of his photographs from that pivotal moment, a mere fraction of the 5,000 he shot in the first week of the invasion.

It was the first time they had been shown there and, unsurprisingly, he was in a reflective mood. “For a long time no one here was interested in remembering,” he told me, “but now I think they start to remember again.”

For a long time, Koudelka, who is 85, also seemed to have little interest in remembering – at least publicly – the remarkable adventure of his own life as a photographer. Two years after the Russian invasion, he left Czechoslovakia and began an extended exile during which he became a nomad of sorts, travelling constantly. His vagabond life became the stuff of legend, particularly among his fellow members of the Magnum photo agency: Koudelka drank slivovitz (a fearsome Czech plum brandy) for breakfast; he slept beneath a desk in Magnum’s office in Paris, or on the floors of friends: he would suddenly disappear for months at a time with his sleeping bag and a rucksack containing a change of clothes, his camera and as many canisters of film as he could carry.

His close friend and fellow photographer Elliott Erwitt described Koudelka to me as “an eccentric, who thinks differently and sees the world differently”, before adding, revealingly, that he was an artist who was “utterly aware of his own legend and his legacy”.

Melissa Harris’s visual biography, intriguingly titled Next, was written with his cooperation, and is a thorough and informative overview of his life and work. Rich in personal ephemera – family portraits, snapshots and glimpses of his many journals – it traces his trajectory from Boskovice, a small town in Moravia, where he had dreams of becoming an engineer, to his status as one of the world’s most revered photographers. Koudelka emerges as a fiercely single-minded individual, whose freedom is synonymous with constant movement. “Never stay for a long time in one place,” he wrote in a diary from the early 1970s. “When you stop somewhere... things start to stick. When you go from one place to another, you are cleaning yourself.”

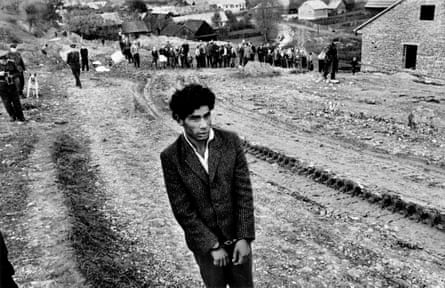

Having fled his homeland, Koudelka seems to have instinctively known that he would never be at home elsewhere. The Roma people he lived among and photographed for his first great book, Gypsies (1975), called him the “romantico clandestino”. His relentless restlessness, which even they considered extreme, informed his choice of early subject matter: Gypsies was followed by another book titled Exiles. In both, his eye for haunting human tableaux and stark, unforgiving landscapes was acute, no more so than in his image Slovakia (Jarabina)(1963), in which a handcuffed young Romani man stands on a hill, with a gaggle of villagers and handful of policemen in the background.

When it was exhibited in a group show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1973, the extended caption incorrectly described it as the moment in which the young man was being taken away to be executed for murder. In fact, Koudelka photographed him when he had been taken back to the scene of the crime by the local police, who were trying to accurately reconstruct the moment. When Koudelka returned to the Slovakian village more than 20 years later, he tells Harris, he somehow managed to track down the man and show him the photograph. “He looked at me,” Koudelka recalled. “He put his arms around me and with great happiness, he said: ‘It’s me! It’s me! It’s me!’”

That particular photograph, even more so than Koudelka’s other haunting images of isolated Roma communities, their rituals and celebrations, is complex in its atmospheric rendering of isolation and belonging. It exemplifies one of the underlying themes of Harris’s book, and of Koudelka’s classic photographs: the sense that, for all his lone wanderings, he is the very opposite of the detached observer. Instead, he is an image-maker whose identification with, and empathy for, his subjects underpins his immersive approach and produces photographs that often possess a kind of grainy romantic realism.

Harris also tracks Koudelka’s various romantic relationships, which were often intense and fleeting, and sketches his relationships with his three children, one of whom, Rebecca, he met for the first time in 2000, almost 30 years after she was born. The abiding sense is of a man whose dedication to his work, and innate wanderlust, precluded the possibility of long-term commitment. “No one can ever help you,” he wrote in one of his journals. “It’s you who has to help yourself.” Alone, and on the move, he seems to have experienced his most rewarding interactions and somehow formed his most enduring friendships. Not so much an eccentric, then, more, as Harris’s book attests, an enigma. His thousands of photographs, he tells her, are “proof that you were alive. That it was not just a dream.”

No comments:

Post a Comment