James Salter: the forgotten hero of American literature

Acclaimed as one of the great postwar American writers, James Salter has, at 87, spent his working life in the shadow of his peers. But his first novel in more than 30 years may finally raise the profile of this former fighter pilot whose books are inspiring a new generation of readers

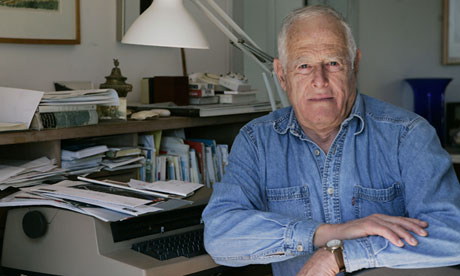

'I always knew writing a novel was a great thing': James Salter at home in Bridgehampton, Long Island, May 2013. Photograph: Ed Betz/Ap

Eight years ago, the writer James Salter received a telephone call out of the blue from an admirer: an American general who had loved his novel The Hunters so much he had ordered copies of it for all his group commanders. The general asked Salter, a former US air force pilot, if he would be interested in going up in an F-16, a fighter 10 times more powerful than the F-86 he'd flown in Korea (The Hunters is based on Salter's experiences in the Korean war, during which he logged more than 100 missions). Salter, whose manner can be diffident, thought for a moment. It was 44 years since he had last sat in a cockpit. Then again, why wouldn't he want to go up? "I suppose so," he finally said. A date was agreed. He would visit Fort Worth, Texas before the month was out.

"So, I flew down there," he says. "And... well, he was a very young guy. He almost didn't look authentic to me. But he was extremely nice." A pause. "No, not nice. That sounds terrible. Like he's a gardener, or something. I mean: a decent man. And he had it all fixed up. He had a flying suit for me with my name on it, and boots and a jacket. It was all terribly touching." Another pause, during which he gives me a look as if to convince himself I'm really interested in all of this – after which, reassured, he is suddenly all nonchalance. To listen to him, his voice so light, his tone so unshowy, flying a jet might be as easy as playing ping pong, or bowling.

"First of all, he took me into operations for a briefing. Things are a little different [in an F-16]. I had to learn how to bale out, and I had to fly on the computer to see if I went cross-eyed, or whatever. So, I made a landing or two, I flew around a little. Then I went into the ready room, where there were a number of pilots waiting, and the general said: 'This is Jim Salter, he wrote The Hunters, and he flew in Korea with "Boots" Blesse [a famous ace who now lies in Arlington National Cemetery], and they all gathered around because they knew Boots Blesse's name, and we talked like the old days, and I could almost imagine that I was one of them.

"It was a lieutenant colonel who took me up. Of course, I had done the same thing myself when I was their age." He drops his voice comically for a moment, and gives a little sigh: "Taken old people around. I could see he was looking at me... my age. I mean, I didn't look 40. I was 79 years old. 'I'll take off,' he said. 'Don't touch anything.' I told him: 'OK, cool.' So, we got in, we took off, we flew around. We were at 5,000 feet. 'You want to fly it a little?' he asked. 'Sure,' I said, and so I did. 'You want to do some rolls?' he asked, and so I did. 'You want to try a loop?' he asked. 'Sure,' I said. We climbed to 10,000 feet. You pick up 425 knots for a loop, and you pull it in four Gs and... that's it. So, I pulled it up, and as I did, I heard the lieutenant say: 'Awesome! Awesome!'" Salter smiles.

And was it awesome for him, too? "No, it wasn't terribly awesome," he says, softly. "But I was pleased to be able to hit the ball. Flying is that kind of thing. You feel... it's a good thing, a physical thing, like hitting a ball. What's so good about hitting a ball? I can't explain it. Do it, and you'll see."

Awesome, awesome. Salter is wary of words like these, however gratifying in the moment. He loves to be praised, but he needs such approval to be unconnected to his age. He doesn't want to be good for 87; he wants only to be good. If this is true of what he can still do in a cockpit given half the chance, it is triply the case of his writing. In the US, his first novel for 34 years has just been published, and while he is boyishly delighted by some of the reviews – "not coda but overture", said the New York Times, acclaiming All That Is as "strikingly original" – he has detected a certain, slightly patronising tone elsewhere: "It's wondrous! they say. It's incredible! This old fucker can hardly stand, and here he is writing a novel." The New Yorker, for instance, chose to call its long and rather snitty profile of him "The Last Book", which was kind of bald. "I suppose it's a fair bet that this might be the last book. But, you know..." His hands flutter meaningfully in the air.

Does he feel his age? Surely not. His back is straight. His eyes are not milky, but extraordinarily blue, like the Mediterranean on a hot day. Above all, he is so interested. At the risk of appearing as bad as the rest of them, I tell him that he doesn't look 87 to me. "It depends on what time of day it is," he says. "In the morning, sitting here for breakfast, in the sun... this is the season when you feel a little bit yourself. I feel OK. You don't have to put on a brave front or something. You have lost your ability to concentrate for a long time, and some of these damn words are slipping away from you. It's like a little slit in your pocket. But you're not incapable of writing."

On this point, at least, it would be hard to disagree. It might have taken him years to write – he settled on its main character about a decade ago, he thinks – but All That Is, which tells the story of a navy veteran and literary publisher, Philip Bowman, over a period of some 40 years, has a grandeur that is all its own. Its handling of time, its elliptical wisdom, and its occasional chest-tightening cruelties are masterful; every paragraph is quietly, carefully good. On the page, moreover, anyone can be young. It is an inordinately vigorous novel. So much feeling. So much sex. Those who pick it up knowing nothing of James Salter will perhaps picture its author to be a young man – a fellow with dark hair, say, and a leather jacket. Salter smiles at this. "Well, he had those things once," he says with a forlorn dip of his head.

Who is James Salter? It may be that you have never heard of him. Salter is not famous the way Philip Roth and John Updike are famous, nor half so prolific; his reputation rests on just two collections of short stories, five (now six) novels and a memoir, Burning the Days. But he is, nevertheless, the kind of American writer who is sometimes called great: a stylist, a purist, a guy who really socks it to you, however elegantly. His books, which are about valour and women and the sadness that doggedly inhabits the everyday, are strangely timeless – they skirt politics, and even brand names, as if such things are a little dirty – and yet they seem also to belong to another age; something in them brings to mind Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, even Graham Greene, beside whose papers Salter's own notebooks lie at the Harry Ransom Centre at the University of Texas.

"It is an article of faith among readers of fiction that James Salter writes American sentences better than anyone writing today," says Richard Ford in his introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of Light Years, the 1975 novel that is surely Salter's masterpiece. Is this true? I can't say. But Light Years, in which a golden marriage first curdles and then dissolves, is certainly an extraordinary book: as ravishing as Gatsby, as plangent as Revolutionary Road, as nimble as Rabbit, Run. The word is – though I don't, alas, get to try one – that Salter mixes a good martini, and this is precisely what Light Years brings to mind. You can feel it going down, burning your throat. All That Is, which stands as a kind of companion piece to it (being about one man's relationships, rather than one marriage), is a gentler, more hopeful affair. But they are hewn from the same stone: the fretfulness that stalks us even in the moments when we should be most content.

Salter lives in Aspen, Colorado and Bridgehampton, Long Island, a double life that sounds glamorous and wealthy, but really isn't. Writing is not remotely glamorous. For him, it's hard-won, and involves "a lot of self-hatred, a lot of despair, a lot of hope, and a lot of just absolute effort". As for his houses, they long predate the skiing movie stars and the Wall Street moguls, and are in any case rather modest. Luckily, he is not one for envy, at least not when it comes to material things. "I was talking to my son the other day about yachts and money," he says. "We were discussing some stupendously rich man, with a crew of 10 for his boat. My son was telling me how much it cost just to fill its tank. Well, I couldn't possibly write a line on a boat like that. I'm not equipped to live in such a way. My requirements seem to be much smaller." The New Yorkeraccused him of nostalgia for a way of life now passed (an accusation based on the fact he once asked guests coming to a New Year's Eve dinner to wear black tie). But this is not the case at all. How could it be? "I'm not nostalgic for it because I have it," he says, waving an arm at the books on the shelf, the pictures on the wall (I meet him in Bridgehampton). His view of American culture? "It's got louder, but it's probably not any worse."

Salter has long felt overlooked, neglected, doubtful of his reputation and whether it would ever amount to anything. With the publication of All That Is, however, he is enjoying a moment: good reviews, the attention of theNew Yorker, which for many years refused to publish his short stories, a packed-to-the-rafters reading with Richard Ford at the 92nd Street Y in Manhattan ("about 500 people," he says, eyes wide). In London, where his book comes out later this month, his publisher is throwing a smart party for him. The British edition of his novel comes garlanded with praise from John Banville and Julian Barnes. A lot of writers claim not to read their reviews, but Salter isn't one of them. "If you walked into a bar on the day of publication and you heard people whispering about your book, you'd be interested, wouldn't you?" he says. "After all, they may like it. That happens occasionally." These past few weeks, then, have been purest oxygen for him.

"The power of the novel in the nation's culture had weakened," thinks Philip Bowman towards the end of All That Is. "It had happened gradually. It was something everyone recognised and ignored. All went on exactly as before, that was the beauty of it. The glory had faded, but fresh faces kept appearing, wanting to be part of it, to be in publishing, which had retained a suggestion of elegance like a pair of beautiful bone-shined shoes owned by a bankrupt man." Is this how Salter sees it, too? "Well, I thought it up to yesterday," he says. "But then I started reading a long piece on the internet, and I thought: perhaps that's rather a stuffy idea. On the internet, everyone is writing. There is a great flowering of writing. So perhaps I'm wrong. Maybe I didn't think it through carefully enough. But you can apply it to Bowman's sort of publishing. Going in to Knopf [Salter's swank US publisher] today is not like going into a publisher 50 years ago. That world is changing."

The British are, he thinks, wrong to be so fixated with the idea of the Great American Novel. It's only a matter of timing, or luck, or coincidence. "America just happened to have some big writers," he says. "I'm not ranking them… [a mischievous smile], but big, colourful and fulfilling. A bunch of them just came along. Your tradition remains. England has a literature unsurpassed. It's just that the centre shifts from time to time. It's not permanent. It's nothing to do with national decline, or national importance. You're just lucky as a country if you have a number of them at a time." In any case, who's to say what is great, and what is not? Only time is the judge. "Cheever is in relative eclipse at the moment, but that might not last. You're lucky if a book stays in print for 30 or 40 years. Writers want a guarantee they'll be read in the future, and we would love to give them that, but we can't."

Still, greatness was an early preoccupation of his. The idea of it was what got him started in the first place: "I always knew writing a novel was a great thing." Salter was born James Horowitz in New Jersey, in 1925, an only child. The household wasn't bookish. His father, George, was in real estate; his mother, Mildred, was from Washington DC, and had once been beautiful and lively ("the dreariness came later"). When he was two, the family moved to New York; he went to high school in the Bronx, where he was two years behind Jack Kerouac. He wrote "terrible poetry" and played football. The plan was that he would go to Stanford, at least in his own mind. But his father, who had attended West Point, the military academy – he graduated first in his class – had other ideas. Subtle pressure was applied. "I knew what my father, more than anything else, wanted me to do. Seventeen, vain, and spoiled by poems, I prepared to enter a remote West Point. I would succeed there, it was hoped, as he had."

He writes of his unpreparedness for this education compellingly inBurning the Days – the shocking drama of it, and his own (to me) remarkable stoicism: "It was the hard school, the forge. To enter you passed, that first day, into an inferno. Demands, many of them incomprehensible, rained down. Always at rigid attention, hair freshly cropped, chin withdrawn and trembling, barked at by unseen voices, we stood or ran like insects from one place to another." It was a place of clanging bells, and shouting, and endless drills: "The feeling of being on a hopeless journey, an exile that would last for years." And you were never alone: "Above all, it was this that marked the life." A hard thing, for a writer.

At first, he was reluctant, even incompetent. But in his second year, things improved; either the system had broken him, or he had embraced its ethos – even he can't say which. He passed an eye test, and joined the army air corps, where he learned to fly. He was good at flying, though there was one early disaster. At sunset on VE Day, he took off on a solo navigation flight; he and the 15 other students participating in the exercise had deliberately been misinformed about the wind. As night fell, he realised he was lost. Soon, his fuel was low. There was nothing for it but to crash-land in what he took for a park. Once his landing lights were on, however, he saw he had made a mistake. "Something went by on the left. Trees, in the middle of the park. I had barely missed them. No landing here." A moment later, more trees. The sound of their leaves on his wing was swiftly followed by the disappearance of said wing. "The plane careened up. It stood poised for an endless moment, one landing light flooding a house into which an instant later it crashed." Luckily, the family inside had rushed outside on hearing his plane (they had taken its appearance as a military salute, for they were welcoming home a son who had been a PoW in Germany). No one was hurt. But Salter made something of an impression on the inhabitants of Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Years later, he received an unsigned card with a postmark from the town. We are still praying for you here, it said.

After the war, he was deployed to Manila and Honolulu, where he flew transport planes and fell in love with the wife of another officer, his best friend. Then, in 1951, he was promoted to fighter jets. Soon after, he volunteered for Korea. Glory days, "the realm long sought". Impossible to choose, from among the crystalline descriptions in Burning the Days, a line to quote. Every sentence is fantastic. But if I had to pick one, it would be from the section in which Salter gives an account of his battle with an enemy MiG, his only kill: "He abruptly rolls over and I follow, as if we are leaping from a wall." What an image, the fantasies of little boys folded inside something so very grave, so very grown-up! In Burning the Days, Salter writes that he felt he was born to fly fighters. But perhaps what he really means is that alone among his colleagues only he would eventually be able to put all this sensation – the sheer unfathomable rush of it – into words.

On tour, he kept a notebook. Later, while he was posted in Germany, he turned these notes into The Hunters. He wrote in secret. "Well, perhaps that's too strong. Secret makes it sound shameful, or treacherous. I would say that I wrote privately. That would be more accurate. Because books and writers were not esteemed." Nor did he use his own name: it was at this point that James Salter was born. When the novel was accepted for publication in 1956, he told only his wife ("a horse country Virginian" with whom he went on to have four children), and when it was serialised in a magazine, he was all innocence. "Let me read it when you finish," he told a pilot who'd pointed it out to him. Salter insists that he hadn't yet decided he was going to be a writer (by this point, he was in line to become a squadron commander); he simply wanted to write this particular book.

"I wanted to be greatly admired [as the author of The Hunters], but unknown." Still, internally, a shift was under way. "The compulsion to fly was going to wane. I knew that. The promise of the compulsion to write was signalling to me. I didn't make my decision until the book was published. Then, I saw that it was possible. I recall the time very clearly. I had confidence, but I was also completely at sea." Only when the film rights were sold – the movie starred Robert Mitchum and Robert Wagner – did he finally resign his commission, a severing he has described as "worse than divorce, emotionally".

Salter and his wife settled along the Hudson in New York (which is whereLight Years would be set). He wrote another air force novel (The Arm of Flesh, later republished as Cassada), but then there came something of hiatus; it was 1967 before he published his next significant book, A Sport and a Pastime, and Light Years did not arrive until 1975. There were distractions. He and a TV writer, Lane Slate, a man he'd met while out selling swimming pools (a sideline), made a short film together about football, Team, Team, Team, which somewhat miraculously won a top prize at the 1962 Venice film festival – and soon, he was writing scripts. These, in turn, led to an introduction to Robert Redford, for whom he would eventually write the screenplay for Downhill Racer, a film about the World Cup Alpine ski circuit.

His last film script was Solo Faces, about rock climbing, a sport he took up himself with some alacrity by way of research. But Redford turned it down, and Salter eventually turned it into a novel – the last one he wrote before All That Is (it came out in 1979). "I wasted time writing films," he says now. "I don't look back on those years as lost, but it wasn't what I should have been doing. I would like to have written more [novels], yes. Most writers can write three times as many books as I have, and still live a life."

The next years were a struggle. A Sport and a Pastime, a book based on a love affair Salter had in France in the early 60s, could not find a publisher, perhaps because there was so much sex in it. Eventually, George Plimpton, the editor of the Paris Review, published it under the journal's own imprint, but it sold fewer than 3,000 copies. Light Yearssold about 8,000 copies, and received mixed reviews – even now, people either love it or hate it, though you have to wonder about those who fall into the latter camp – which made its author despondent; he had such high hopes. In 1980, five years after Salter and his wife divorced (the marriage seems to have been a painful mistake right from the start), he found his daughter, Allan, dead in the shower of a cabin next to his house in Aspen; she had been electrocuted.

"I have never been able to write the story," he says in Burning the Days. "I reach a certain point and cannot go on. The death of kings can be recited, but not of one's own child." Along the way, other horrors. In 1967, he had watched the television, aghast, as the news broke of a fire on Apollo 1. Grissom and White, two of the astronauts who were killed, had flown with Salter in Korea. "Something lodged in my chest, a feeling I could not swallow... The capsule had become a reliquary, a furnace. They had inhaled fire, their lungs had turned to ash."

James Salter with his wife Kay Eldredge in 2012. Photograph: Andrew Southam

James Salter with his wife Kay Eldredge in 2012. Photograph: Andrew Southam

The 80s, though, also marked a turning point. In Aspen, Salter met a writer 20 years his junior, Kay Eldredge. She was smitten, and turned up at his door, claiming to have left her bracelet at his house. "A pretty basic idea," he says. "But rather cunning." And romantic! "Yes, romantic." Did it work? "Yes, I asked for her number." They had a son together, in 1985, and married a few years later. "A long marriage: very sympathetic, very grand. I don't know what more you can ask for." She is the dedicatee ofAll That Is.

In 1989, his short story collection, Dusk and Other Stories, won the PEN/Faulkner award; meanwhile, both A Sport and a Pastime andLight Years were republished. His reputation as "a writer's writer" (whatever that means) began to build. There was a glow at the end of the tunnel, after all. Earlier this year, he was awarded a Windham Campbell prize by Yale University worth $150,000. Will he stop writing now, as Philip Roth claims to have done? No. "But I will never again write a book in which there's a single sexual act. They're expecting it now!" Actually, he can't be sure he will write more. "You have your brains, but it's energy and desire that make you write a book." The thought of the last two abandoning him hangs in the air, unspoken.

After we finish talking, Salter takes me for lunch at a nearby restaurant, a place once frequented by Truman Capote, whose photograph hangs over the bar. "We're just friends," he says to the waitress with a smile. When he orders an egg white omelette, and I express my amazement that such a thing could exist, he warns me to not make him sound like "one of those health nuts" in my piece. "This is what old people eat," he says, with a low laugh (as it happens, I won't do this; I have the food book he wrote with Eldredge, Life is Meals: A Food Lover's Book of Days; Salter is something of a bon viveur, on the quiet).

Afterwards, I have a choice. I can have an ice cream, or he can give me a short tour. I choose the tour, which is how I come to see the house – pigeon grey with a fairytale turret – where Nora Ephron lived when she was married to Carl Bernstein. Salter is fun to be with, dashing and droll, and you leave his company with a certain reluctance. At the bus stop for Manhattan, I wave at his car wildly as he moves off. But he doesn't see me. His eyes are on the road. He looks determined: as stoical – you might say as heroic – as ever.

All That Is is published by Picador on 23 May 2013

No comments:

Post a Comment