This is a slow train anyway, and it has slowed some more for the curve. Jackson is the only passenger left, and the next stop is about twenty miles ahead. Then the stop at Ripley, then Kincardine and the lake. He is in luck and it’s not to be wasted. Already he has taken his ticket stub out of its overhead notch.

He heaves his bag, and sees it land just nicely, in between the rails. No choice now — the train’s not going to get any slower.

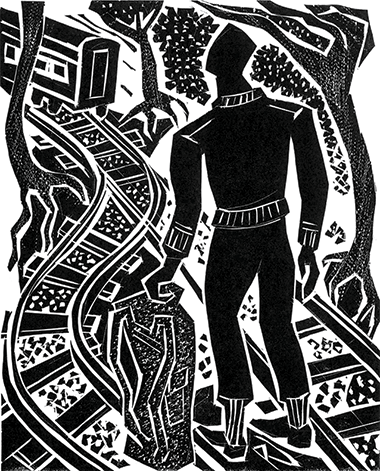

He takes his chance. A young man in good shape, agile as he’ll ever be. But the leap, the landing, disappoints him. He’s stiffer than he’d thought, the stillness pitches him forward, his palms come down hard on the gravel between the ties, he’s scraped the skin. Nerves.

The train is out of sight; he hears it putting on a bit of speed, clear of the curve. He spits on his hurting hands, getting the gravel out. Then picks up his bag and starts walking back in the direction he has just covered on the train. If he followed the train he would show up at the station there well after dark. He’d still be able to complain that he’d fallen asleep and wakened all mixed up, thinking he’d slept through his stop when he hadn’t, jumped off all confused.

He would have been believed. Coming home from so far away, from Germany and the war, he could have got mixed up in his head. It’s not too late, he would be where he was supposed to be before midnight. But all the time he’s thinking this he’s walking in the opposite direction. He doesn’t know many names of trees. Maples, that everybody knows. Pines. He’d thought that where he jumped was in some woods, but it wasn’t. The trees are just along the track, thick on the embankment, but he can see the flash of fields behind them. Fields green or rusty or yellow. Pasture, crops, stubble. He knows just that much. It’s still August.

And once the noise of the train has been swallowed up he realizes there isn’t the perfect quiet around that he would have expected. Plenty of disturbance here and there, a shaking of the dry August leaves that wasn’t wind, a racket of unknown, unseen birds chastising him.

People he’d met in the past few years seemed to think that if you weren’t from a city, you were from the country. And that was not true. Jackson himself was the son of a plumber. He had never been in a stable in his life or herded cows or stoked grain. Or found himself as now stumping along a railway track that seemed to have reverted from its normal purpose of carrying people and freight to become a province of wild apple trees and thorny berry bushes and trailing grapevines and crows scolding from perches you could not see. And right now a garter snake slithering between the rails, perfectly confident he won’t be quick enough to tramp on and murder it. He does know enough to figure that it’s harmless, but its confidence riles him.

The little jersey, whose name was Margaret Rose, could usually be counted on to show up at the stable door for milking twice a day, morning and evening. Belle didn’t often have to call her. But this morning she was too interested in something down by the dip of the pasture field, or in the trees that hid the railway tracks on the other side of the fence. She heard Belle’s whistle and then her call, and started out reluctantly. But then decided to go back for another look.

Belle set the pail and stool down and started tramping through the morning-wet grass.

“So-boss. So-boss.”

She was half coaxing, half scolding.

Something moved in the trees. A man’s voice called out that it was all right.

Well of course it was all right. Did he think she was afraid of him attacking Margaret Rose who had her horns still on?

Climbing over the rail fence, he waved in what he might have considered a reassuring way.

That was too much for Margaret Rose, she had to put on a display. Jump one way, then another. Toss of the wicked little horns. Nothing much, but jerseys can always surprise you with their speed and spurts of temper. Belle called out, to scold her and reassure him.

“She won’t hurt you. Just don’t move. It’s her nerves.”

Now she noticed the bag he had hold of. That was what had caused the trouble. She had thought he was just out walking the tracks, but he was going somewhere.

“That’s what the trouble is. She’s upset with your bag. If you could just lay it down for a moment. I have to get her back towards the barn to milk her.”

He did as she asked, and then stood watching, not wanting to move an inch.

She got Margaret Rose headed back to where the pail was, and the stool, on this side of the barn.

“You can pick it up now,” she said. “As long as you don’t wave it around at her. You’re a soldier, aren’t you? If you wait till I get her milked I can get you some breakfast. Good night, I’ve got out of breath. That’s a stupid name when you have to holler at her. Margaret Rose.”

She was a short, sturdy woman with straight hair, gray mixed in with what was fair, and childish bangs.

“I’m the one responsible for it,” she said, as she got herself settled. “I’m a royalist. Or I used to be. I have porridge made, on the back of the stove. It won’t take me long to milk. If you wouldn’t mind going round the barn and waiting where she can’t see you. It’s too bad I can’t offer you an egg. We used to keep hens but the foxes kept getting them and we just got fed up.”

We. We used to keep hens. That meant she had a man around somewhere.

“Porridge is good. I’ll be glad to pay you.”

“No need. Just get out of the way for a bit. She’s got herself too interested to let her milk down.”

He took himself off around the barn. It was in bad shape. He peered between the boards to see what kind of a car she had, but all he could make out in there was an old buggy and some other wrecks of machinery.

The white paint on the house was peeling and going gray. A window with boards nailed across it, where there must have been broken glass. The dilapidated henhouse where she had mentioned the foxes getting the hens. Shingles in a pile.

If there was a man on the place he must have been an invalid, else paralyzed with laziness.

There was a road running by. A small fenced field in front of the house, a dirt road. And in the field a dappled, peaceable-looking horse. A cow he could see reasons for keeping, but a horse? Even before the war people on farms were getting rid of them, tractors were the coming thing. And she hadn’t looked like the sort to trot round on horseback just for the fun of it. Then it struck him. The buggy in the barn. It was no relic, it was all she had.

For a while now he’d been hearing a peculiar sound. The road rose up a hill, and from over that hill came a clip-clop, clip-clop. Along with the clip-clop some little tinkle or whistling.

Now then. Over the hill came a box on wheels, being pulled by two quite small horses. Smaller than the ones in the field but no end livelier. And in the box sat a half dozen or so little men. All dressed in black, with proper black hats on their heads.

The sound was coming from them. It was singing. Discrete high-pitched little voices, as sweet as could be. They never looked at him as they went by.

It chilled him. The buggy in the barn and the horse in the field were nothing in comparison.

He was still standing there looking one way and another when he heard her call, “All finished.” She was standing by the house.

“This is where to go in and out,” she said of the back door. “The front is stuck since last winter, and it just refuses to open, you’d think it was still frozen.”

They walked on planks laid over an uneven dirt floor, in a darkness provided by the boarded-up window. It was as chilly there as it had been in the hollow where he’d slept. He had wakened again and again, trying to scrunch himself into a position where he could stay warm. The woman didn’t shiver here — she gave off a smell of frank healthy exertion and what was likely the cow’s hide.

She poured the fresh milk into a basin and covered it with a piece of cheesecloth she kept by, then led him into the main part of the house. The windows there had no curtains, so the light was coming in. Also the woodstove had been in use. There was a sink with a hand-pump, a table with oilcloth on it worn in some places to shreds, and a couch covered with a patchy old quilt.

Also a pillow that had shed some feathers.

So far, not so bad, though old and shabby. There was a use for everything you could see. But raise your eyes and up there on shelves was pile on pile of newspapers or magazines or just some kind of papers, up to the ceiling.

He had to ask her, was she not afraid of fire? A woodstove too.

“Oh, I’m always here. I mean, I sleep here and everything. There isn’t any place else I can keep the draughts out. I’m watchful. I haven’t had a chimney fire even. A couple of times it got too hot and I just threw some baking powder on it. Nothing to it.

“My mother had to be here anyway,” she said. “There was no place else for her to be comfortable. I had her cot in here. I kept an eye on everything. I did think of moving all the papers into the front room but it’s really too damp in there, they would all be ruined. She died in May. Just when the weather got decent. She lived to hear about the end of the war on the radio. She understood perfectly. She lost her speech a long time ago but she could understand. I’m so used to her not speaking that sometimes I think she’s here but she’s not.”

Jackson felt it was up to him to say he was sorry.

“Oh well. It was coming. Just lucky it wasn’t in the winter.”

She served him oatmeal porridge and tea.

“Not too strong? The tea?”

Mouth full, he shook his head.

“I never economize on tea. If it comes to that why not drink hot water? We did run out when the weather got so bad last winter. The hydro gave out and the radio gave out and the sea gave out. I had a rope round the back door to hang on to when I went out to milk. I was going to get Margaret Rose into the back kitchen but I figured she’d get too upset with the storm and I couldn’t hold her. Anyway she survived. We all survived.”

Finding a place in the conversation, he asked were there any dwarfs in the neighborhood?

“Not that I’ve noticed.”

“In a cart?”

“Oh. Were they sitting? It must have been the little Mennonite boys. They drive their cart to church and they sing all the way. The girls have to go in the buggy but they let the boys ride in the cart.”

“They never looked at me.”

“They wouldn’t. I used to say to Mother that we lived on the right road because we were just like the Mennonites. The horse and buggy and we drink our milk unpasteurized but the only thing is, neither one of us can sing.

“When Mother died they brought so much food I was eating it for weeks. They must have thought there’d be a wake or something. I’m lucky to have them there.

“But they are lucky too, because they are supposed to practice charity and here I am practically on their doorstep and an occasion for charity if you ever saw one.”

He offered to pay her when he’d finished but she batted her hand at his money.

But there was one thing, she said. If before he went he could manage to fix the horse trough.

What this involved was actually making a new horse trough, and in order to do that he had to hunt around for any materials and tools he could find. It took him all day, and she served him pancakes and Mennonite maple syrup for supper. She said that if he’d only come a week later she might have fed him fresh jam. She picked the wild berries growing along the railway track.

They sat on kitchen chairs outside the back door until after the sun went down. She was telling him something about how she came to be here and he was listening, but not paying full attention because he was looking around and thinking how this place was on its last legs but not absolutely hopeless, if somebody wanted to settle down and fix things up. A certain investment of money was needed, but a greater investment of time and energy. It could be a challenge. He could almost bring himself to regret that he was moving on.

Her father — she called him her daddy — had bought this place just for the summers, she said, and then he decided that they might as well live here all year round. He could work anywhere, because he made his living with a column for the Toronto Telegram. (Jackson just for a second embarrassingly pictured this as a real column holding or helping to hold up a building.) The mailman took what was written and it was sent off on the train. He wrote about all sorts of things that happened, mentioning Belle’s mother occasionally but calling her Princess Casamassima, out of some book. Her mother might have been the reason they stayed year round. She had caught the terrible flu of 1918 in which so many people died, and when she came out of it she was a mute. Not really, because she could make sounds all right, but she seemed to have lost words. Or they had lost her. She had to learn all over again to feed herself and go to the bathroom but one thing she never learned was to keep her clothes on in the hot weather. So you wouldn’t want her just wandering around and being a laughingstock, on some city street. Belle was away at a school in the winters. It took him a little effort to realize that what she referred to as Bishop Strawn was a school. It was in Toronto and she was surprised he hadn’t heard of it. It was full of rich girls but also had girls like herself who got special money from relations or wills to go there. It taught her to be rather snooty, she said. And it didn’t give her any idea of what she would do for a living.

But that was all settled for her by the accident. Walking along the railway track, as he often liked to do on a summer evening, her father was hit by a train. She and her mother had already gone to bed when it happened and Belle thought it must be a farm animal loose on the tracks, but her mother was moaning dreadfully and seemed to know first thing.

Sometimes a girl she had been friends with at school would write to ask her what on earth she could find to do up there, but little did they know. There was milking and cooking and taking care of her mother and she had the hens at that time as well. She learned how to cut up potatoes so each part has an eye, and plant them and dig them up the next summer. She had not learned to drive and when the war came she sold her daddy’s car. The Mennonites let her have a horse that was not good for farmwork anymore, and one of them taught her how to harness and drive it.

One of the old friends came up to visit her and thought the way she was living was a hoot. She wanted her to go back to Toronto but what about her mother? Her mother was a lot quieter now and kept her clothes on, also enjoyed listening to the radio, the opera on Saturday afternoons. Of course she could do that in Toronto but Belle didn’t like to uproot her. Or maybe it was herself she was talking about, who was scared of uproot.

The first thing he had to do was to make some rooms other than the kitchen fit to sleep in, come the cold weather. He had some mice to get rid of and even some rats, now coming in from the cooling weather. He asked her why she’d never invested in a cat and heard a piece of her peculiar logic. She said it would always be killing things and dragging them for her to look at, which she didn’t want to do. He kept a sharp ear open for the snap of the traps, and got rid of them before she knew what had happened. Then he lectured about the papers filling up the kitchen, the firetrap problem, and she agreed to move them, if the front room could be got free of damp. That became his main job. He invested in a heater and repaired the walls, and persuaded her to spend the better part of a month climbing down and getting the papers, rereading and reorganizing them and fitting them on the shelves he had made.

She told him then that the papers contained her father’s book. Sometimes she called it a novel. He did not think to ask anything about it but one day she told him it was about two people named Matilda and Stephen. A historical novel.

“You remember your history?”He had finished five years of high school with respectable marks and a very good showing in trigonometry and geography but did not remember much history. In his final year, anyway, all you could think about was that you were going to the war.

He said, “Not altogether.”

“You’d remember altogether if you went to Bishop Strawn. You’d have had it rammed down your throat. English history, anyway.”

She said that Stephen had been a hero. A man of honor, far too good for his times. He was that rare person who wasn’t all out for himself or looking to break his word the moment it was convenient to do so. Consequently and finally he was not a success.

And then Matilda. She was a straight descendant of William the Conqueror and as cruel and haughty as you might expect. Though there might be people stupid enough to defend her because she was a woman.

“If he could have finished it would have been a very fine novel.”

Jackson of course wasn’t stupid. He knew that books existed because people sat down and wrote them. They didn’t just appear out of the blue. But why, was the question. There were books already in existence, plenty of them. Two of which he had to read at school. A Tale of Two Cities and Huckleberry Finn, each of them with language that wore you down, though in different ways. And that was understandable. They were written in the past. What puzzled him, though he didn’t intend to let on, was why anybody would want to sit down and do another one, in the present. Now.

A tragedy, said Belle briskly, and Jackson didn’t know if it was her father she was talking about or the people in the book that had not been finished. Anyway, now that this room was livable his mind was on the roof. No use to fix up a room and have the state of the roof render it unlivable again in a year or two. He had managed to patch the roof so that it would do her a couple more winters but he could not guarantee more than that. And he still planned to be on his way by Christmas.

The Mennonite families on the next farm ran to older girls and the younger boys he had seen, not strong enough yet to take on heavier chores. Jackson had been able to hire himself out to them during the fall harvest. He had been brought in to eat with the others and to his surprise found that the girls behaved giddily as they served him, they were not at all mute as he had expected. The mothers kept an eye on them, he noticed, and the fathers kept an eye on him. All safe.

And of course with Belle not a thing had to be spoken of. She was — he had found this out — sixteen years older than he was. To mention it, even to joke about it, would spoil everything. She was a certain kind of woman, he a certain kind of man.

The town where they shopped, when they needed to, was called Oriole. It was in the opposite direction from the town where he had grown up. He tied up the horse in the United Church shed there, since there were of course no hitching posts left on the main street. At first he was leery of the hardware store and the barbershop. But soon he realized something about small towns which he should have realized just from growing up in one. They did not have much to do with each other, unless it was for games run off in the ballpark or the hockey arena, where all was a fervent made-up sort of hostility. When people needed to shop for something their own stores could not supply they went to a city. The same when they wanted to consult a doctor other than the ones their own town could offer. He didn’t run into anybody familiar, and nobody showed a curiosity about him, though they might look twice at the horse. In the winter months, not even that, because the back roads were not plowed and people taking their milk to the creamery or eggs to the grocery had to make do with horses.

Belle always stopped to see what movie was on though she had no intention of going to see any of them. Her knowledge of movies and movie stars was extensive but came from some years back. For instance she could tell you whom Clark Gable was married to in real life before he became Rhett Butler.

Soon Jackson was going to get his hair cut when he needed to and buying his tobacco when he ran out. He smoked now like a farmer, rolling his own and never lighting up indoors.

Secondhand cars didn’t become available for a while but when they did, with the new models finally on the scene and farmers who’d made money in the way ready to turn in the old ones, he had a talk with Belle. The horse Freckles was God knows how old and stubborn on any sort of hill.

He found that the car dealer had been taking notice of him, though not counting on a visit.

“I always thought you and your sister was Mennonites but ones that wore a different kind of outfit,” the dealer said.

That shook Jackson up a little but at least it was better than husband and wife. It made him realize how he must have aged and changed over the years, and how the person who had jumped off the train, that skinny nerve-wracked soldier, would not be so recognizable in the man he was now. Whereas Belle, so far as he could see, was stopped at some point in life where she remained a grown-up child. And her talk reinforced this impression, jumping back and forth, into the past and out again, so that it seemed she made no difference between their last trip to town and the last movie she had seen with her mother and father, or the comical occasion when Margaret Rose — now dead — had tipped her horns at a worried Jackson.

It was the second car they had owned that took them to Toronto in the summer of 1962. This was a trip they had not anticipated and it came at an awkward time for Jackson. For one thing, he was building a new horse barn for the Mennonites, who were busy with the crops, and for another, he had his own harvest of vegetables coming on, which he planned to sell to the grocery store in Oriole. But Belle had a lump that she had finally been persuaded to pay attention to, and she was booked now for an operation in Toronto.

What a change, Belle kept saying. Are you so sure we are still in Canada?

This was before they got past Kitchener. Once they got on the new highway she was truly alarmed, imploring him to find a side road or else turn around and go home. He found himself speaking sharply to her — the traffic was surprising him too. She stayed quiet all the way after that, and he had no way of knowing whether she had her eyes closed, had given up, or was praying. He had never known her to pray.

Even this morning she had tried to get him to change his mind about going. She said the lump was getting smaller, not larger. Since the health insurance for everybody had come in, she said, nobody did anything but run to the doctor and make their lives into one long drama of hospitals and operations, which did nothing but prolong the period of being a nuisance at the end of life.

She calmed down and cheered up once they got to their turnoff and were actually in the city. They found themselves on Avenue Road, and in spite of exclamations about how everything had changed, she seemed to be able on every block to recognize something she knew. There was the apartment building where one of the teachers from Bishop Strawn had lived (that was only the pronunciation, the name was spelled Strachan, as she had told him a while ago). In the basement there was a shop where you could buy milk and cigarettes and the newspaper. Wouldn’t it be strange, she said, if you could go in there and still find the Telegram, where there would be not only her father’s name but his smudgy picture, taken when he still had all his hair?

Then a little cry, and down a side street she had seen the very church — she could swear it was the very church — in which her parents had been married. They had taken her there to show her, though it wasn’t a church they were members of. They did not go to any church, far from it. Her father said they had been married in the basement but her mother said the vestry.

Her mother could talk then, that was when she could talk. Perhaps there was a law at the time, to make you get married in a church or it wasn’t legal.

At Eglinton she saw the subway sign.

“Just think, I have never been on a subway train.”

She said this with some sort of mixed pain and pride.

“Imagine remaining so ignorant.”

At the hospital they were ready for her. She continued to be lively, telling them about her horrors in the traffic and about the changes, wondering if there was still such a show put on at Christmas by Eaton’s store. And did anybody remember the Telegram?

“You should have driven in through Chinatown,” one of the nurses said. “Now that’s something.”

“I’ll look forward to seeing it on my way home.” She laughed, and said, “If I get to go home.”

“Now don’t be silly.”

Another nurse was talking to Jackson about where he’d parked the car, and telling him where to move it so he wouldn’t get a ticket. Also making sure that he knew about the accommodations for out-of-town relations, much cheaper than you’d have to pay at a hotel.

Belle would be put to bed now, they said. A doctor would come to have a look at her, and Jackson could come back later to say good night. He might find her a little dopey by that time, they said.

She overheard, and said that she was dopey all the time so he wouldn’t be surprised, and there was a little laugh all round.

The nurse took him to sign something before he left. He hesitated where it asked for what relation. Then he wrote “friend.”

When he came back in the evening he did see a change, though he would not have described Belle then as dopey. They had put her into some kind of green cloth sack that left her neck and most of her arms quite bare. He had seldom seen her so bare, or noticed the raw-looking cords that stretched between her collarbone and her chin.

She was angry that her mouth was dry.

“They won’t let me have anything but the meanest little sip of water.”

She wanted him to go and get her a Coke, something that she never drank in her life as far as he knew.

“There’s a machine down the hall — there must be. I see people going by with a bottle in their hands and it makes me so thirsty.”

He said he couldn’t go against orders.

Tears came into her eyes and she turned pettishly away.

“I want to go home.”

“Soon you will.”

“You could help me find my clothes.”

“No I couldn’t.”

“If you won’t I’ll do it myself. I’ll get myself to the train station myself.”

“There isn’t any passenger train that goes up our way anymore.”

Abruptly then, she seemed to give up on her plans for escape.

In a few moments she started to recall the house and all the improvements that they — or mostly he — had made on it. The white paint shining on the outside and even the back kitchen whitewashed and furnished with a plank floor. The roof reshingled and the windows restored to their plain old style, and most of all glories, the plumbing that was such a joy in the wintertime.

“If you hadn’t shown up I’d have soon been living in absolute squalor.”

He didn’t voice his opinion that she already had been.

“When I come out of this I am going to make a will,” she said. “All yours. You won’t have wasted your labors.”

He had of course thought about this, and you would have expected that the prospects of ownership would have brought a sober satisfaction to him, though he would have expressed a truthful and companionable hope that nothing would happen too soon. But no. It all seemed quite to have little to do with him, to be quite far away.

She returned to her fret.

“Oh, I wish I was there and not here.”

“You’ll feel a lot better when you wake up after the operation.”

Though from everything that he had heard that was a whopping lie. Suddenly he felt so tired.

He had spoken closer to the truth than he could have guessed. Two days after the lump’s removal Belle was sitting up in a different room, eager to greet him and not at all disturbed by the moans coming from a woman behind the curtain in the next bed. That was more or less what she — Belle — had sounded like yesterday, when he never got her to open her eyes or notice him at all.

“Don’t pay any attention to her,” said Belle. “She’s completely out of it. Probably doesn’t feel a thing. She’ll come round tomorrow bright as a dollar. Or maybe she won’t.”

A somewhat satisfied, institutional authority was showing, a veteran’s callousness. She was sitting up in bed and swallowing some kind of bright orange drink through a conveniently bent straw. She looked a lot younger than the woman he had brought to the hospital such a short time before.

She wanted to know if he was getting enough sleep, if he’d found some place where he liked to eat, if the weather had not been too warm for walking, if he had found time to visit the Royal Ontario Museum, as she thought she had advised.

But she could not concentrate on his replies. She seemed to be in an inner state of amazement. Controlled amazement.

“Oh, I do have to tell you,” she said, breaking right into his explanation of why he had not got to the museum. “Oh, don’t look so alarmed. You’ll make me laugh with that face on, it’ll hurt my stitches. Why on earth should I be thinking of laughing anyway? It’s a dreadfully sad thing really, it’s a tragedy. You know about my father, what I’ve told you about my father —”

The thing he noticed was that she said father instead of daddy.

“My father and my mother —”

She seemed to have to search around and get started again.

“The house was in better shape then than when you first got to see it. Well it would be. We used that room at the top of the stairs for our bathroom. Of course we had to carry the water up and down. Only later, when you came, I was using the downstairs. With the shelves in it, you know, that had been a pantry?”

How could she not remember that he had taken out the shelves and put in the bathroom? He was the one who had done it.

“Oh well, what does it matter?” she said, as if she followed his thoughts. “So I had heated the water and I carried it upstairs to have my sponge bath. And I took off my clothes. Well I would. There was a big mirror over the sink, you see it had a sink like a real bathroom only you had to pull out the plug and let the water back into the pail when you were finished. The toilet was elsewhere. You get the picture. So I proceeded to wash myself and I was bare naked, naturally. It must have been around nine o’clock at night so there was plenty of light. It was summer, did I say? That little room facing west?

“Then I heard steps and of course it was Daddy. My father. He must have been finished putting Mother to bed. I heard the steps coming up the stairs and I did notice they sounded heavy. Somewhat not like usual. Very deliberate. Or maybe that was just my impression afterwards. You are apt to dramatize things afterwards. The steps stopped right outside the bathroom door and if I thought anything I thought, Oh, he must be tired. I didn’t have any bolt across the door because of course there wasn’t one. You just assumed somebody was in there if the door was closed.

“So he was standing outside the door and I didn’t think anything of it and then he opened the door and he just stood and looked at me. And I have to say what I mean. Looking at all of me, not just my face. My face looking into the mirror and him looking at me in the mirror and also what was behind me and I couldn’t see. It wasn’t in any sense a normal look.

“I’ll tell you what I thought. I thought, He’s walking in his sleep. I didn’t know what to do, because you are not supposed to startle anybody that is sleepwalking.

“But then he said, ‘Excuse me,’ and I knew he was not asleep. But he spoke in a funny kind of voice, I mean it was a strange voice. Very much as if he was disgusted with me. Or mad at me, I didn’t know. Then he left the door open and just went away down the hall. I dried myself and got into my nightgown and went to bed and went to sleep right away. When I got up in the morning there was the water I had drained and I didn’t want to go near it but I did.

“But everything seemed normal and he was up already typing away. He just yelled good morning and then he asked me how to spell some word. The way he often did, because I was a better speller. So I did and then I said he should learn how to spell if he thought he was a writer, he was hopeless. But then sometime later in the day when I was washing some dishes he came up right behind me and I froze. He just said, ‘Belle, I’m sorry.’ And I thought, Oh, I wish he had not said that. It scared me. I knew it was true he was sorry but he was putting it out in the open in a way I could not ignore. I just said, ‘That’s okay,’ but I couldn’t make myself say it in an easy voice or as if it really was okay.

“I couldn’t. I had to let him know he had changed us. I went to throw out the dishwater and then I went back to whatever else I was doing and not another word. Later I got Mother up from her nap and I had supper ready and I called him but he didn’t come. I said to Mother that he must have gone for a walk. He often did when he got stuck in his writing. I helped mother cut up her food.

“I didn’t know where he could have gone. I got Mother ready for bed though that was his job. Then I heard the train coming and all at once the commotion and the screeching which was the train brakes and I must have known what had happened though I don’t know exactly when I knew.

“I told you before. I told you he got run over by the train.

“But I’m not telling you this, I am not telling you just to be harrowing. At first I couldn’t stand it and for the longest time I was actually making myself think that he was walking along the tracks with his mind on his work and never heard the train. That was the story all right. I was not going to think it was about me or even what it primarily was about. Sex.

“It seems to me just now I have got a real understanding of it and that it was nobody’s fault. It was the fault of human sex in a tragic situation. Me growing up there and Mother the way she was and Daddy, naturally, the way he would be. Not my fault nor his fault.

“There should be acknowledgment, that’s all I mean, places where people can go if they are in a situation. And not be all ashamed and guilty about it. If you think I mean brothels, you are right. If you think prostitutes, right again. Do you understand?”

Jackson, looking over her head, said yes.

“I feel so released. It’s not that I don’t feel the tragedy, but I have in a way got outside the tragedy, is what I mean. It is just the mistakes of humanity that are tragic, if you see what I mean. You mustn’t think because I’m smiling that I don’t have compassion. I have serious compassion. But I have to say I am relieved. At the same time. I have to say I somehow feel happy. You are not embarrassed by listening to all this?”

“No.”

“You realize I am in a slightly abnormal state. I know I am. There is this abnormal clarity. I mean in everything. Everything so clear. I am so grateful for it.”

The woman on the bed had not let up on her rhythmical groaning all through this. Jackson felt as if that refrain had entered into his head.

He heard the nurse’s squishy shoes in the hall and hoped they would enter this room. They did.

The nurse said that she had to give Belle her sleepy-time pill. He was afraid she would tell him to kiss her good night. He had noticed that a lot of kissing went on in the hospital. He was glad when he stood up that there was no mention of it.

“See you tomorrow.”

He woke up early, and decided to take a walk before breakfast. He had slept all right but told himself he ought to take a break from the hospital air. It wasn’t that he was worried so much by the change in Belle. He thought it was possible or even probable that she would get back to normal, either today or in a couple more days. She might not even remember the story she had told him. Which would be a blessing.

The sun was well up, as you could expect at this time of year, and the buses and streetcars were already pretty full. He walked south for a bit, then turned west onto Dundas Street, and after a while found himself in the Chinatown he had heard about. Loads of recognizable and many not-so-recognizable vegetables were being trundled into shops, and small, skinned, apparently edible animals were already hanging up for sale. The streets were full of illegally parked trucks and noisy, desperate-sounding Chinese. All the high-pitched clamor sounded like they had a war going on, but probably to them it was just everyday. Nevertheless he felt like getting out of the way, and he went into a restaurant run by Chinese but advertising an ordinary breakfast of eggs and bacon. When he came out of there he intended to turn around and retrace his steps.

But instead he found himself heading south again. He had got onto a residential street lined with tall and fairly narrow brick houses. They must have been built before people in the area felt any need for driveways or possibly before they even had cars. Before there were such things as cars. He walked until he saw a sign for Queen Street, which he had heard of. He turned west again and after a few blocks he came to an obstacle. In front of a doughnut shop he ran into a small crowd of people. They were stopped by an ambulance, backed right up on the sidewalk so you could not get by. Some of them were complaining about the delay and asking loudly if it was even legal to park an ambulance on the sidewalk, and others were looking peaceful enough while they chatted about what the trouble might be. Death was mentioned, some of the onlookers speaking of various candidates and others saying that was the only legal excuse for the vehicle being where it was.

The man who was finally carried out, bound to the stretcher, was surely not dead or they’d have had his face covered. He was not being carried out through the doughnut shop, as some had jokingly predicted — that was some sort of dig at the quality of the doughnuts — but through the main door of the building. It was a decent enough brick apartment building five stories high, housing a Laundromat as well as the doughnut shop on its main floor. The name carved over its main door suggested pride as well as some foolishness in its past.

Bonnie Dundee.

A man not in ambulance uniform came out last. He stood there looking with exasperation at the crowd that was now thinking of breaking up. The only thing to wait for now was the grand wail of the ambulance as it found its way onto the street and tore away.

Jackson was one of those who didn’t bother to walk away. He wouldn’t have said he was curious about any of this, more that he was just waiting for the inevitable turn he had been expecting, to take him back to where he’d come from. The man who had come out of the building walked over and asked if he was in a hurry.

No. Not specially.

This man was the owner of the building. The man taken away in the ambulance was the caretaker and superintendent.

“I’ve got to get to the hospital and see what’s the trouble with him. Right as rain yesterday. Never complained. Nobody close that I can call on, so far as I know. The worst, I can’t find the keys. Not on him and not usually where he keeps them. So I got to go home and get my spares and I just wondered, could you keep a watch on things meanwhile? I got to go home and I got to go to the hospital too. I could ask some of the tenants but I’d just rather not, if you know what I mean. Natural curiosity or something.”

He asked again if Jackson was sure he would not mind and Jackson said no, fine.

“Just keep an eye for anybody going in, out, ask to see their keys. Tell them it’s an emergency, won’t be long.”

He was leaving, then turned around.

“You might as well sit down.”

There was a chair Jackson had not noticed. Folded and pushed out of the way so the ambulance could park. It was just one of those canvas chairs but comfortable enough and sturdy. Jackson set it down with thanks in a spot where it would not interfere with passersby or apartment dwellers. No notice was taken of him. He had been about to mention the hospital and the fact that he himself had to get back there before too long. But the man had been in a hurry, and he already had enough on his mind, and he had already made the point that he would be as quick as he could.

Jackson realized, once he got sitting down, just how long he’d been on his feet walking here or there.

The man had told him to get a coffee or something to eat from the doughnut shop if he felt the need.

“Just tell them my name.”

But that Jackson did not even know.

When the owner came back he apologized for being late. The fact was that the man who had been taken away in the ambulance had died. Arrangements had to be made. A new set of keys had become necessary. Here they were. There’d be some sort of funeral involving those in the building who had been around a long time. Notice in the paper might bring in a few more. A troublesome spell, till this was sorted out.

It would solve the problem. If Jackson could. Temporarily. It only had to be temporarily.

Yes, all right with him, Jackson said.

If he wanted to take a little time, that could be managed. Right after the funeral and some disposal of goods. A few days he could have then, to get his affairs together and do the proper moving in.

That would not be necessary, Jackson said. His affairs were together and his possessions were on his back.

Naturally this roused a little suspicion. Jackson was not surprised a couple of days later to hear that this new employer had made a visit to the police. But all was well, apparently. He had emerged as just one of those loners who may have got themselves in too deep some way or another but have not been guilty of breaking any law.

It looked as if there was no search party under way.

As a rule, Jackson liked to have older people in the building. And as a rule, single people. Not zombies. People with interests. Talent. The sort of talent that had been noticed once, made some kind of a living once, though not enough to hang on to all through a life. An announcer whose voice had been familiar on the radio during the war but whose vocal cords were shot to pieces now. Most people probably believed he was dead. But here he was in his bachelor suite, keeping up with the news and subscribing to the Globe and Mail, which he passed on to Jackson in case there was anything of interest to him in it.

Once there was.

Marjorie Isabella Treece, daughter of Willard Treece, longtime columnist for the Toronto Telegram, and his wife Helena (née Abbott) Treece, has passed away after a courageous battle with cancer. Oriole paper please copy. July 18, 1965.

No mention of where she had been living. Probably in Toronto. She had lasted maybe longer than he had expected. He didn’t spend a moment’s time picturing the rooms of work he’d done on her place. He didn’t have to — such things were often recalled in dreams, and his feeling then was more of exasperation than of longing, as if he had to get to work on something that had not been finished.

In the building of Bonnie Dundee, there had to be consideration of human beings, as he tackled the upkeep of their surroundings and of what the women might call their nests. (The men were usually uneasy about any improvement meaning a raise in the rent.) He talked them round, with good respectful manners and good fiscal sense, and the place became one with a waiting list. “We could fill it all up without a loony in the place,” said the owner. But Jackson pointed out that the loonys as he called them were generally tidier than average, besides which they were a minority. There was a woman who had once played in the Toronto Symphony and an inventor who had truly just missed out on a fortune for one of his inventions and had not given up yet though he was over eighty. And a Hungarian refugee actor whose accent was not in demand but who still had a commercial running somewhere in the world. They were all well behaved, even those who went out to the Epicure Bar every day at noon and stayed till closing. Also they had friends among the truly famous who might show up once in a blue moon for a visit. Nor should it be sneezed at that the Bonnie Dundee had an in-house preacher, on shaky terms with whatever his church might be but always able to officiate when called upon.

People did often stay until his office was necessary.

An exception was the young couple named Candace and Quincy who never settled their rent and skipped out in the middle of the night. The owner happened to have been in charge when they came looking for a room, and he excused himself for his bad choice by saying that a fresh face was needed around the place. Candace’s. Not the boyfriend’s. The boyfriend was a crude sort of jerk.

On a hot summer day Jackson had the double back doors, the delivery doors, open, to let in what air he could while he worked at varnishing a table. It was a pretty table he’d got for nothing because its polish was all worn away. He thought it would look nice to put the mail on, in the entryway.

He was able to be out of the office because the owner was in there checking some rents.

There was a light touch on the front doorbell. Jackson was ready to haul himself up, cleaning his brush, because he thought the owner in the midst of figures might not care to be disturbed. But it was all right, he heard the door being opened, a woman’s voice. A voice on the edge of exhaustion, yet able to maintain something of its charm, its absolute assurance that whatever it said would win over anybody who came within listening range.

She would probably have got that from her father the preacher. He remembered thinking this before.

This was the last address she had, she said, for her daughter. She was looking for her daughter. Candace her daughter. She had come here from British Columbia. From Kelowna where she and the girl’s father lived.

Ileane. That woman was Ileane.

He heard her ask if it was possible for her to sit down. Then the owner pulling out his — Jackson’s — chair.

Toronto so much hotter than she had expected, though she knew Ontario, had grown up there.

She wondered if she could possibly beg for a glass of water.

She must have put her head down in her hands as her voice grew muffled. The owner came out into the hall and dropped some change into the machine to get a 7-Up. He might have thought that more ladylike than a Coke.

Around the corner he saw Jackson listening, and he made a gesture that he, Jackson, should take over, being perhaps more used to distraught tenants. But Jackson shook his head violently. No.

She did not stay distraught long.

She begged the owner’s pardon and he said the heat could play those tricks today.

Now about Candace. They had left within a month, it could be three weeks ago. No forwarding address.

“In such cases there usually isn’t —”

She got the hint.

“Oh, of course I can settle —”

There was some muttering and rustling while this was done. Then, “I don’t suppose you could let me see where they were living —”

“The tenant isn’t in now. But even if he was I don’t think he’d agree to it.”

“Of course. That’s silly.”

“Was there anything else you were particularly interested in?”

“Oh no. No. You’ve been kind. I’ve taken your time.”

She had got up now, and they were moving. Out of the office, down the couple of steps to the front door. Then the door was opened and street noises swallowed up her farewells if there were any.

However she had been defeated, she would get herself out with a good grace.

Jackson came out of hiding as the owner returned to the office.

“Surprise,” was all the owner said. “We got our money.”

He was a man who was basically incurious, at least about personal matters. A thing which Jackson valued in him.

Of course he would like to have seen her. He hadn’t got much of an impression of the daughter. Her hair was blond but very likely dyed. No more than twenty though it was sometimes hard to tell nowadays. Very much under the thumb of the boyfriend. Run away from home, run away from your bills, break your parents’ hearts, for a sulky piece of goods, a boyfriend.

Where was Kelowna? In the west somewhere. British Columbia. A long way to come looking. Of course she was a persistent woman. An optimist. Probably that was true of her still. She had married. Unless the girl was out of wedlock and that struck him as very unlikely. She’d be sure, sure of herself the next time, she wouldn’t be one for tragedy. The girl wouldn’t be, either. She’d come home when she’d had enough. She might bring along a baby but that was all the style nowadays.

Shortly before Christmas in the year 1940 there had been an uproar in the high school. It had even reached the third floor where the clamor of typewriters and adding machines usually kept all the downstairs noises at bay. The oldest girls in the school were up there — girls who last year had been learning Latin and biology and European history and were now learning to type.

One of these was Ileane Bishop, a minister’s daughter, although there were no bishops in her father’s United Church. Ileane had arrived with her family when she was in grade nine and for five years, because of the custom of alphabetical seating, she had sat behind Jackson Adams. By that time Jackson’s phenomenal shyness and silence had been accepted by everybody else in the class but it was new to her, and during the next five years, by not acknowledging it, she had produced a thaw. She borrowed erasers and pen nibs and geometry tools from him, not so much to break the ice as because she was naturally scatterbrained. They exchanged answers to problems and marked each other’s tests. When they met on the street they said hello, and to her his hello was actually more than a mumble — it had two syllables and an emphasis to it. Nothing much was presumed beyond that except that they had certain jokes. Ileane was not a shy girl but she was clever and aloof and not particularly popular, and that seemed to suit him.

From her position on the stairs, when all these older girls came out to see the ruckus, Ileane along with all the others was surprised to see that one of the two boys causing it was Jackson. The other was Bill Watts. Boys who only a year ago had sat hunched over books and shuffled dutifully between one classroom and another. Now in army uniforms they looked twice the size they had been, their powerful boots making a ferocious noise as they galloped around. They were shouting out that school was canceled for the day, because everybody had to join the army. They were distributing cigarettes everywhere, even tossing them on the floor where they could be picked up by boys who didn’t even shave.

Careless warriors, whooping invaders. Drunk up to their eyeballs.

“I’m no piker,” they were yelling.

The principal was trying to order them out. But because this was still early in the war and there was as yet some awe and veneration concerning the boys who had signed up, wrapping themselves so to speak in the costume of death, he was not able to show the ruthlessness he would have called upon a year later.

“Now now,” he said.

“I’m no piker,” Billy Watts told him.

Jackson had his mouth open probably to say the same, but at that moment his eyes met the eyes of Ileane Bishop and a certain piece of knowledge passed between them.

Ileane Bishop understood, it seemed, that Jackson was truly drunk but that the effect of this was to enable him to play drunk, therefore the drunkenness displayed could be managed. (Billy Watts was just drunk, through and through.) With this understanding Ileane walked down the stairs, smiling, and accepted a cigarette, which she held unlit between her fingers. She linked arms with both heroes and marched them out of the school.

Once outside they lit up their cigarettes.

There was a conflict of opinion about this later, in Ileane’s father’s congregation. Some said Ileane had not actually smoked hers, just pretended to pacify the boys, while others said she certainly had. Smoked.

Billy did put his arms around Ileane and tried to kiss her, but he stumbled and sat down on the school steps and crowed like a rooster. Within two years he would be dead.

Meanwhile he had to be got home, and Jackson pulled him so that they could get his arms over their shoulders and drag him along. Fortunately his house was not far from the school. They left him there, passed out on the front steps, and entered into a conversation.

Jackson did not want to go home. Why not? Because his stepmother was there, he said. He hated his stepmother. Why? No reason.

Ileane knew that his mother had died in a car accident when he was very small — this was sometimes taken to account for his shyness. She thought that the drink was probably making him exaggerate, but she didn’t try to make him talk about it any further.

“Okay,” she said. “You can stay at my place.”

It just happened that Ileane’s mother herself was away, looking after Ileane’s sick grandmother. Ileane was at the time keeping house in a haphazard way for her father and her two young brothers. This was fortunate. Not that her mother would have made a fuss, but she would have wanted to know the ins and outs and who was this boy? At the very least she would have made Ileane go to school as usual.

A soldier and a girl, so suddenly close. Where there had been nothing all this time but logarithms and declensions.

Ileane’s father didn’t pay attention to them. He was more interested in the war than some of his parishioners thought a minister should be, and this made him proud to have a soldier in the house. Also he was unhappy not to be able to send his daughter to college, on his minister’s salary, because he had to put something by to send her brothers someday. That made him lenient.

Jackson and Ileane didn’t go to the movies. They didn’t go to the dance hall. They went for walks, in any weather and often after dark. Sometimes they went into a restaurant and drank coffee, but did not try to be friendly to anybody. What was the matter with them? Were they falling in love?

Ileane went by herself to Jackson’s house to collect his bag. His stepmother raised her skinny eyebrows and showed her bright false teeth and tried to look as if she was ready for some fun.

She asked what they were up to.

“You better watch that stuff,” she said, with a big laugh. She had a reputation for being a loudmouth but people said she didn’t mean any harm. Ileane was especially ladylike, partly to annoy her.

She told Jackson what had been said, and made it funny, but he didn’t laugh.

She apologized.

“I guess you get too much in the habit of caricaturing people, living in a parsonage,” she said.

He said it was okay.

That time at the parsonage turned out to be Jackson’s last leave. They wrote to each other. Ileane wrote about finishing her typing and shorthand and getting a job in the office of the town clerk. In spite of what she had said about caricatures she was determinedly satirical about everything, more than she had been in school. Maybe she thought that someone at war needed joking.

When hurry-up marriages had to be arranged through the clerk’s office she would refer to the “virgin bride.”

And when she mentioned some stodgy minister visiting the parsonage and sleeping in the spare room she wondered if the mattress would induce naughty dreams.

He wrote about the crowds on the Île de France and the ducking around to avoid U-boats. When he got to England he bought a bicycle and he told her about places he had biked around to see if they were not out of bounds.

Then about being picked to take a map course which meant he would work behind the lines if there was ever such a need (he meant of course after D-Day).

These letters though more prosaic than hers were always signed with love. When D-Day did come there was what she called an agonizing silence but she understood the reason for it, and when he wrote again all was well, though details impossible.

In this letter he spoke as she had been doing, about marriage.

And at last V-E Day and the voyage home. He mentioned showers of summer stars overhead.

Ileane had learned to sew. She was making a new summer dress in honor of his homecoming, a dress of lime-green rayon silk with a full skirt and cap sleeves, worn with a narrow belt of gold imitation leather. She meant to wind a ribbon of the same green material around the crown of her summer straw hat.

“All this is being described to you so you will notice me and know it’s me and not go running off with some other beautiful woman who happens to be at the train station.”

He mailed his letter to her from Halifax, telling her that he would be on the evening train on Saturday. He said that he remembered her very well and there was no danger of getting her mixed up with another woman even if the train station happened to be swarming with them that evening.

On their last evening they had sat up late in the parsonage kitchen where there was the picture of King George VI you saw everywhere that year. And the words beneath it.

I said to the man who stood at the gate of the year, “Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.”

And he replied, “Go out into the darkness and put your hand into the hand of God. That shall be to you better than light and safer than a known way.”

Then they went upstairs very quietly and he went to bed in the spare room. Her coming to him must have been by mutual agreement because he was not surprised.

It was a disaster. But by the way she behaved, she didn’t seem to know. The more disaster, the more frantic became her stifled displays of passion. There was no way he could stop her trying, or explain. Was it possible a girl could know so little? They parted finally as if all had gone well. And the next morning said goodbye in the presence of her father and brothers. In a short while the letters began, loving as could be. He got drunk and tried once more, in Southampton. But the woman said, “That’s enough, sonny boy, you’re down and out.”

Athing he didn’t like was women or girls dressing up. Gloves, hats, swishy skirts, all some demand and bother about it. But how could she know that? Lime green, he wasn’t sure he knew the color. It sounded like acid.

Then it came to him quite easily, that a person could just not be there.

Would she tell herself or tell anybody else, that she must have mistaken the date? He’d told himself that she would make up some lie, surely — she was resourceful, after all.

Now that she was gone, Jackson felt a wish to see her. Her voice even in distress had been marvelously unchanged. Drawing all importance to itself, musical levels. He could never ask the owner what she looked like, whether her hair was still dark, or gray, and she herself skinny or gone stout. He had not paid much attention to the daughter, except on the matter of disliking the boyfriend.

She had married. Unless she’d had the child by herself and that wasn’t likely. She would have a prosperous husband, other children. This the one to break her heart.

That kind of girl would come back. She’d be too spoiled to stay away. She’d come back when necessary. Even the mother — Ileane — hadn’t she had some spoiled air about her, some way of arranging the world and the truth to suit herself, as if nothing could foil her for long?

The next day whatever ease he had about the woman passing from his life was gone. She knew this place, she might come back. She might settle herself in for a while, walking up and down these streets, trying to find where the trail was warm. Humbly but not really humbly making inquiries of people, in that spoiled cajoling voice. It was possible he would run into her right outside this door.

Things could be locked up, it only took some determination. When he was as young as six or seven he locked up his stepmother’s fooling, what she called her fooling or her teasing when she gave him a bath. He ran out on the street after dark and she got him in but she saw there’d be some real running away if she didn’t stop so she stopped. She said he was no fun because she could never say that anybody hated her. But she knew he hated her even if she couldn’t account for it and she stopped.

He spent three more nights in the building called Bonnie Dundee. He wrote an account for the owner of every apartment and when and what upkeep was due. He said that he had been called away, without indicating why or where to. He emptied his bank account and packed the few things belonging to him. In the evening, late in the evening, he got on the train. He slept off and on during the night and in one of those snatches he saw the little Mennonite boys go by in their cart. He heard their small sweet voices singing.

This had happened before in his dreams.

In the morning he got off in Kapuskasing. He could smell the mills, and was encouraged by the cooler air.

No comments:

Post a Comment