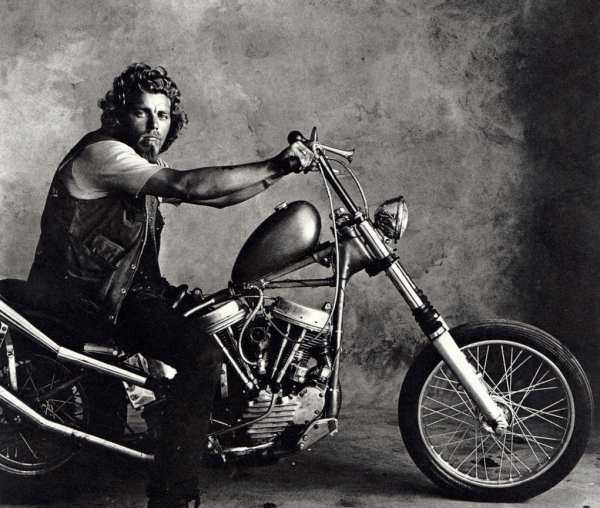

Irving Penn – Doug, Hells Angels (San Francisco), 1967. Appeared in Look magazine, January, 1968.

Irving Penn

FROM HELLS ANGELS

TO HITCHCOCK

THE INCREDIBLES

This Hell’s Angels motorcyclist writes no songs of protest. His actions, his very appearance, says all he wants to say to us. Thus, a lifestyle becomes a statement about the world and, in a sense, a work of art. Irving Penn went to San Francisco to photograph some of the people who outrage and lure us being what they are. Looking past current rages and entertainment, Penn placed these people in a neutral, ageless environment. His pictures, accompanied only by fragments of conversation are addressed not just to the now but to the days to come.

–Look magazine, January, 1968

Irving Penn – Hells Angels (San Francisco), 1967. Appeared in Look magazine, January of 1968.

-THE OUTRAGEOUS

There’s only one thing that really means anything to me and that’s the Hell’s Angels patch I wear. I can get me anything else– a new bike, a new old lady or money– but I can’t get me another patch.

We’ve had a few deaths this year, but otherwise, it’s been a good year. By that I mean we haven’t had much police harassment.

…It’s like being brothers. Like every man in the club’s your brother.

Power. That’s what it feels like when we ride in. On a three day weekend, we might have one-fifty, two-hundred bikes out on a run. People all get excited when they see us coming, and– I don’t know– it’s beautiful.

You know what it is, it’s a mind-blower. They come around with movie cameras. It’s really beautiful.

If someone messed-up one of our brothers, it would be total retaliation. An eye for an eye.

My brothers– that’s my whole life. My brothers. That’s all I’ve got.

–Look magazine, January, 1968

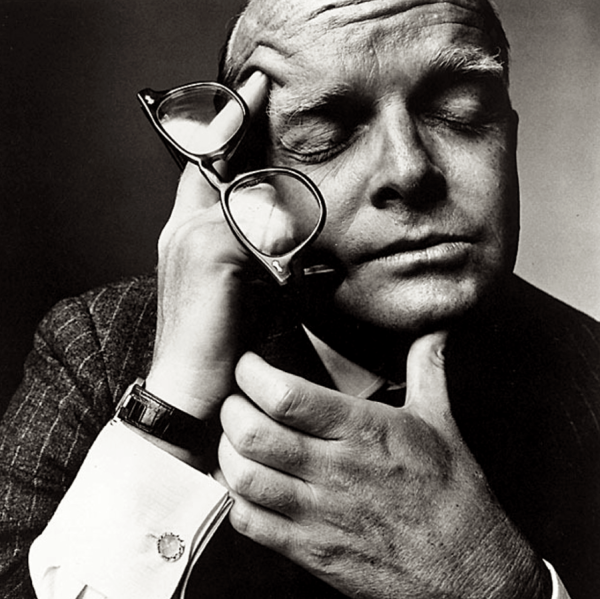

Irving Penn – Alfred Hitchcock

Penn’s portrait composition made him an iconoclast to contemporary photographers. Abandoning grand and fanciful scenery, he embraced austere and stark settings. Cigarette butts and scraps of string littered the floor of his studios. For his portrait, Alfred Hitchcock sat upon cardboard boxes covered with scrap carpet. Penn sandwiched some subjects (among them Elsa Schiaparelli and the Duchess of Windsor) into tight corners. He didn’t stand for anyone who objected. “One sitter said, ‘You’re going to have to clean that up.’ He went home unphotographed,” Penn once recounted.

–Libby Richardson for Dossier

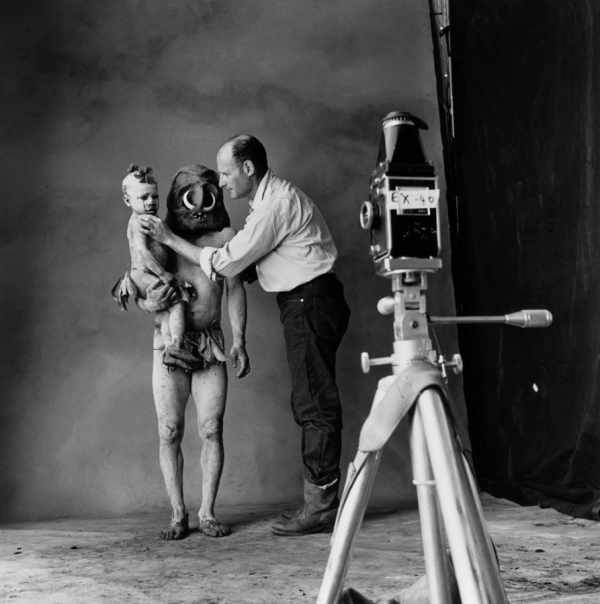

Irving Penn – Dorian Leigh and Maurice Tillet, 1945.

Maurice Tillet (1903 – August 4, 1954) was a professional wrestler known as The French Angel, who was a fan favorite back in the early 1940s. Born in France, Tillet could allegedly speak 14 languages, was a poet, and had early aspirations of being an actor. In his twenties, he developed acromegaly, a rare disease that causes bones to grow out of control. Tillet moved to the U.S. where he capitalized on his extreme appearance by becoming a professional wrestler.

In 1940, four young anthropologists from Harvard took Maurice Tillet’s head and body measurements–

Mr. Tillet is the victim (or, as a wrestler, the beneficiary) of pituitary overdevelopment, resulting in acromegaly—enlargement of the face and jaws. The Harvardmen X-rayed his head, found the sella turcica, which houses the pituitary, considerably enlarged. They measured the tremendous, coffin-shaped face, found it 7.16 inches wide, 7.05 inches long from nose-bridge to jaw-point. They also noted huge protuberances over the eyebrows and at the back of the head, an elevation like a ridgepole from front to back of the cranium.

It seemed likely that pituitary excess set in after the Angel’s long bones had stopped growing, otherwise he might have been a giant. His overdevelopment is lateral. Though just under 5 ft. 10 in. tall, he weighs 276 Ibs. One investigator declared: “The collar bones and rib cage are the most massive I have ever seen. The tremendous nuchal [back-of-the-neck] musculature is quite beyond anything I have ever conceived.”

The anthropologists found M. Tillet “intelligent, very appealing, kindly and gentle.” In short, they liked him. At an afternoon party, he refused sherry and cigarets, took tea and cookies. Like most French commoners, he has a profound respect for the learned professions. He asked Earnest Albert Hooton, famed bellwether of Harvard anthropology, for a signed photograph. Hooton complied, and received from the Angel an elegant letter of thanks, in French, with practically no spelling mistakes.

–TIME magazine, 1940

Irving Penn – Pablo Picasso at La Californie, Cannes, France, 1957. Photo @ Irving Penn for Vogue.

By 1957, Irving Penn had stripped away not only any gratuitous props but also any bodily references or gestures that could have compromised the unique individuality of the famed Spanish artist, by then already established as one of the art world’s most luminary figures. The close-up portrait is skillfully and almost perfectly centered by Picasso’s cyclopean eye, paying homage to the Cubist style that he was instrumental in popularizing. References to the style, in fact, abound in the photograph– the strong tonal contrasts, the cape slicing the face at an unconventional angle, the abstraction of the ear, the different lines dissecting the plain; the portrait is far more akin to Picasso’s gris-toned Buste de Femme, 1956, than any of Penn’s other portraits. It becomes more of a probable self-visualization by Picasso rather than a regimented projection by the photographer of how a portrait should be. Ultimately, Pablo Picasso at La Californie, Cannes, is a carefully nuanced souvenir commemorating the legacy of not one, but two great masters, both delicately revealing themselves through different sides of the same lens.

Irving Penn – Truman Capote, 1965. “In Cold Blood” was released in 1965, and created a wave of acclaim and controversy that would carry Capote for years to come– making him one of America’s most talked about writers ever. And a work of art this important deserved a grand celebration that was equally epic. So in 1966, Capote decided to host a party that would be his “great, big, all-time spectacular present” to himself. Some might even say that the 1966 Masked Black and White Ball was truly one of his greatest works ever.

The photographer Irving Penn

In portrait photography there is something more profound we seek inside a person, while being painfully aware that a limitation of our medium is that the inside is recordable only so far as it is apparent on the outside.

–Irving Penn

No comments:

Post a Comment