Top 10 runaway mothers in fiction

From Nancy Mitford’s ‘the Bolter’ – so named for her serial monogamy – to the mother of Kramer vs Kramer, here are the best mums on the runLaura Lippman

Wed 21 March 2018

Do all mothers fantasise about fleeing their families, if only for a weekend? Or do we simply crave the vicarious thrill of reading about something we know we’ll never do? I’ve long been obsessed with runaway mother stories, relatively rare in fiction. Gone Girl? Sure. Gone Mommy? Not so much. A woman who leaves her family is seen as starkly unnatural. Maybe that’s why so many of my favourite runaway novels play the subject for laughs, or relegate it to a subplot.

Still, I have long wanted to play with this trope and use it for a straight-up crime novel, one as dark as I could imagine. What kind of woman leaves her family? That’s the question that animated my new book Sunburn, but it’s also central to these 10 very different novels.

1. Ladder of Years by Anne Tyler

This wry, big-hearted novel is quintessential book club fodder, meant to be dissected with other women, preferably over wine and snacks. Delia Grinstead, still somewhat unformed at the age of 40, bolts from her family on a beach vacation, only to find a new life caring for the child of another runaway mother. This is Tyler at her best, which is as good as it gets.

This wry, big-hearted novel is quintessential book club fodder, meant to be dissected with other women, preferably over wine and snacks. Delia Grinstead, still somewhat unformed at the age of 40, bolts from her family on a beach vacation, only to find a new life caring for the child of another runaway mother. This is Tyler at her best, which is as good as it gets.

2. Kinflicks by Lisa Alther

This hilarious 1976 debut centres on one woman’s flirtations with many personae, almost all dictated by her partner and/or mentor of the moment. Ginny Hull Babcock frames her life as a Hegelian odyssey of thesis, antithesis and synthesis, but she finds being the mother of a toddler particularly challenging. Technically, Ginny’s husband throws her out, but she doesn’t return to fetch her daughter.

This hilarious 1976 debut centres on one woman’s flirtations with many personae, almost all dictated by her partner and/or mentor of the moment. Ginny Hull Babcock frames her life as a Hegelian odyssey of thesis, antithesis and synthesis, but she finds being the mother of a toddler particularly challenging. Technically, Ginny’s husband throws her out, but she doesn’t return to fetch her daughter.

3. The Women’s Room by Marilyn French

In French’s seminal novel about second-wave feminists at Harvard, the main character, Mira, leaves her two sons with her ex-husband when she decides to attend graduate school. But their relationship actually improves when she pursues her own dreams. By the end, Mira is bitter and disappointed, but she has solid relationships with both her sons.

In French’s seminal novel about second-wave feminists at Harvard, the main character, Mira, leaves her two sons with her ex-husband when she decides to attend graduate school. But their relationship actually improves when she pursues her own dreams. By the end, Mira is bitter and disappointed, but she has solid relationships with both her sons.

|

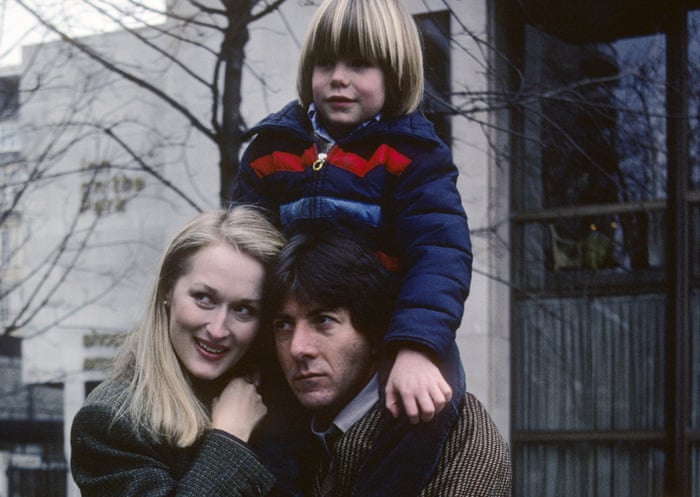

| Meryl Streep, Dustin Hoffman and Justin Henry in the 1979 film adaptation of Avery Corman’s novel Kramer vs Kramer. Photograph: Tom Wargacki |

This 1977 novel has aged better than I expected. Corman does his best to find empathy for Joanna Kramer, the mother who flees and then returns to demand full custody of the son she abandoned. After an acrimonious trial, the judge grants her wish, and then she decides she doesn’t want her son after all – a maddeningly convenient “happy” ending for her ex-husband. Is it a happy ending for the child, though? Corman seems to think so.

It’s hard to write a hilarious Gone Mommy book, but Semple pulled it off in this sly 2012 novel. Semple uses a wide sampling of written formats – report cards, correspondence, school memos, police reports – to craft this ultimately empathic portrait of an overwhelmed woman weighed down by her past.

6. Lady Audley’s Secret by Mary Elizabeth Braddon

For years, I thought this classic “sensation novel” was the invention of an American children’s writer, Maud Hart Lovelace, who used it as an example of a salacious “dime store” novel. It’s not only a real novel, it’s based on a real woman: Constance Kent. Decried by some in its time, Lady Audley’s Secret is now taught in universities as a feminist classic. Elaine Showalter, writing in the London Review of Books, noted: “While [Braddon] condemns Lady Audley’s crimes, Braddon also hints … that women are frustrated and destructive because they are confined to passive domestic lives.”

For years, I thought this classic “sensation novel” was the invention of an American children’s writer, Maud Hart Lovelace, who used it as an example of a salacious “dime store” novel. It’s not only a real novel, it’s based on a real woman: Constance Kent. Decried by some in its time, Lady Audley’s Secret is now taught in universities as a feminist classic. Elaine Showalter, writing in the London Review of Books, noted: “While [Braddon] condemns Lady Audley’s crimes, Braddon also hints … that women are frustrated and destructive because they are confined to passive domestic lives.”

7. Did You Ever Have a Family by Bill Clegg

June Reid has holed up in a seaside motel thousands of miles from her home, determined not to tell her story. After losing her entire family and her boyfriend in a tragic accident, June has lost any sense of herself. It turns out that someone can be a runaway mother even when she no longer has a family to escape. This novel slowly and gracefully answers the question in its title.

June Reid has holed up in a seaside motel thousands of miles from her home, determined not to tell her story. After losing her entire family and her boyfriend in a tragic accident, June has lost any sense of herself. It turns out that someone can be a runaway mother even when she no longer has a family to escape. This novel slowly and gracefully answers the question in its title.

This novel follows its titular characters in the year after the death of the family patriarch. Lydia Mansfield, the younger, usually dutiful daughter, decides to leave her marriage and only takes one of her two sons with her. She believes her decision is merely pragmatic – her older son prefers living in the family house, while the younger one needs more supervision – and is shocked to discover that the school psychologist sees her as a selfish, indifferent mother. It’s a small plot point in a sprawling, satisfying book about three women recalibrating their identities.

When I taught creative writing in college and asked students what they read for pleasure, Voigt’s name came up time and again. Homecoming is the first book in the so-called Tillerman cycle and it begins with four siblings being abandoned in a shopping mall parking lot. It falls to the eldest, 13-year-old Dicey, to keep the family intact. The saga spans seven books; the mother’s mysterious disappearance is resolved in the second, when it’s revealed she’s a catatonic patient in a psychiatric hospital.

With their mother known as “the Bolter” due to being a serial monogamist, how will her daughters learn to make good choices in their own relationships? That’s an inevitable question in this 1945 comic novel, about which Zoë Heller wrote: “But beneath the brittle surface of Mitford’s wit there is something infinitely more melancholy at work – something that is apt to snag you and pull you into its dark undertow when you are least expecting it.” Heller theorises that Pursuit is a love-it-or-hate-it book – making it a lot like runaway mothers, whom we either sympathise with or revile.

No comments:

Post a Comment