Interview

Robert Crumb: ‘I was born weird'

He’s obsessed with ‘spectacular rear ends’ and he calls his fans scum. Yet comic artist Robert Crumb is at risk of becoming respectable. As his new show opens, he talks about filth, fetishes and his idea of fun

Claire Armistead

Sunday 24 April 2016

R

obert Crumb is caught in traffic, allowing us time to snoop out the best place for a photoshoot in the upmarket London gallery where more than 50 of his pictures are on display. It all looks so well mannered, this orderly line of black-and-white illustrations, and then you peer into the pictures and the familiar rude energy comes roistering out.

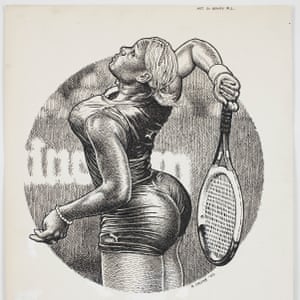

We decide that we will place him between an erotic rear view of the tennis player Serena Williams and a homely portrait of his wife of almost 40 years, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, in bed with her laptop. Aline is the chunky brunette who features in so much of Robert’s work - not least in the three issues of Art & Beauty magazine that are the subject of this exhibition.

It is Robert, not Aline, who I have come to interview, and whose pictures are on sale at a starting price of $30,000 (£20,800), but their art is so intertwined that it’s hard to understand either in isolation. One collaboration, unprecedented in the history of comics or indeed any art, had husband and wife each drawing themselves in the throes of sex with each other.

As we wait for the great man to arrive, Lucas Zwirner, the 25-year-old editor of the gallery’s publishing outlet, gives a learned explanation of the appeal of Crumb’s work to a new generation. “What’s exciting about the work is his openness to his own desire and erotics,” he enthuses. “There’s something irreconcilable at the heart of the work that doesn’t resolve towards a single vision of beauty, and which is at odds with much contemporary art. It’s about seduction and repulsion. You are drawn into the work and you are judging yourself as you look at it.”

Or, as Crumb says when he finally shuffles in, clad in funereal black and wearing his trademark wire glasses: “The dirt’s on the wall.” At 72, he is a paler, frailer version of the priapic nerd of more than half a century of self-portraits.

Art & Beauty showcases a less well-known side of him: the lifelong junk shop rummager and connoisseur of vintage media, which he values for the craftsmanship of “the golden age of graphic art”. Published in 1996 and 2002, with the third volume yet to hit the streets, the project was inspired by a soft porn magazine of the 1920s that smuggled risque photographs past the censor under the titular fig leaf Art & Beauty Magazine for Art Lovers and Art Students.

Some of its pictures are copied directly from vintage magazines – not least two ethnographic images, Handsome Women of the Formidable Zulu Race, in the second volume, and Three African Women from Brazzaville, Congo, in the third. These decorously posed tableaux speak to Crumb’s less decorous fascination with the bodies of black women.

Which brings us to that picture of Serena Williams, caught mid-smash at Flushing Meadow in 2002, with her breasts and backside jutting from a black Lycra catsuit. The inscription below the picture reads: “A HIGHLY SATISFYING CHALLENGE FOR THE ARTIST’S SKILLS ARE THE GLEAMING HIGHLIGHTS ON THE RESPLENDENT CONTOURS OF TENNIS CHAMPION SERENA WILLIAM AS SHE APPEARED ON THE FIRST NIGHT OF THE US OPEN …”

It’s an extreme image, arresting and disturbing, and when I say as much he responds a little defensively: “It was traced from a photograph.”

Yes, but why that picture?

“It’s my personal fetish or fixation.”

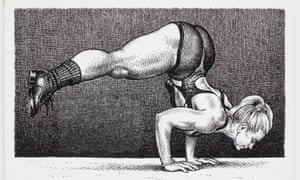

The fetish is not with Serena Williams as tennis champion so much as with her “spectacular back end”. His insistence that “I don’t care what colour they are” is complicated by another caption beneath a blonde gymnast astride a Swiss exercise ball: “The lovely Coco is renowned the world over as a white girl who is the proud possessor of a striking physical attribute most often claimed by women of African descent.”

Part of the paradox of Crumb’s art is that the objects of his erotic fixation are often dynamic, powerful women, depicted in gymnastics or yoga or sport. He traces this fetish back to his childhood, explaining morosely: “I was always a contrarian. My wife says sometimes I’m too much so – born weird. I always felt there’s something odd and off about my nervous system. If everybody’s walking forward, I want to walk backwards.

“During adolescence I couldn’t fit in, and it was very, very painful. But it fired me to develop my own aesthetic. I was very much in pain about being this outcast, but it freed me to drop that Hollywood ideal and pursue the people that I thought attractive.”

When he became successful in the 1960s with creations such as Fritz the Cat or Mr Natural, the mystic druid, “certain eccentric kinds of women got interested in me.” One of them was his first wife, Dana Morgan, and together, they hawked “cheap, stapled comics” on the streets: “My wife was pregnant and we sold them out of a baby pram.” In 1978, he was married a second time, to Aline, making it a condition of their relationship that he could not be monogamous. They have a daughter Sophie, now a comics artist herself.

A few miles away from Crumb’s pumped-up fantasy women, Aline’s work is on display at the House of Illustration, as part of an exhibition of work by female comic artists. In a talk that evening she will be hailed as a feminist pioneer. “It’s nice to be getting a little attention every once in a while,” she says drily.

In the 1970s and 80s, while Aline’s reputation grew as a chronicler of the messiness of family life, Crumb’s portrayal of women, and his sexually rampant self-portraiture, led to vilification by feminist critics. “It had some validity,” he says now. “My work is full of anger towards women. I was sent to Catholic school with scary nuns and I was rejected by girls at high school. I sort of got it out of my system, but anger is normal between the sexes. OK, it can go to the top and men can harm women, but if anyone says they are not angry I don’t believe it, especially while your libido is still going. The men who are most charming are often the most contemptuous.”

Like who? “Like Sam Shepard,” he snaps. “His work is just a seduction of women.” He has said similar things about Martin Amis and Christopher Hitchens.

In the 90s, his ascent to the high table of art began. A 1994 documentary by his friend and bandmate Terry Zwigoff won the grand jury prize at the Sundance film festival (the two had formed a retro band, R Crumb and His Cheap Suit Serenaders, in the 70s), and the hefty The R Crumb Coffee Table Art Book was published in 1997. Three years later, he was picked up by the New York art dealer Paul Morris. “It was like being a tramp outside a fancy restaurant watching people eat and someone suddenly says, ‘Come in and eat with us.’ I never aspired to that other world of symphony orchestras and ballet. I was the child of popular culture. I just wanted to get my work published,” he says.

Morris explains how, in early exhibitions, he had to put alarms on Crumb’s work to foil hardcore fans whose sense of entitlement extended to the right to walk off with the pictures. “The scum of the earth. They’re my people,” chortles Crumb, who is tickled by the contradictions of his two worlds. Collectors of cheap comics insist on pristine copies, while fine-art connoisseurs prize the “white-out” of Tipp-Exed corrections that vein his Art & Beauty pictures. He exploited this to the max with four Waiting for Food series – drawings on place mats, which were then sold individually. “Collectors love to get a little marinara sauce with their art.”

Even before the third edition of Art & Beauty has hit the streets courtesy of his old publisher, Fantagraphics, the images have been collected into an elegant hardback, edited by Zwirner, that doubles as an exhibition catalogue and retails at £24.

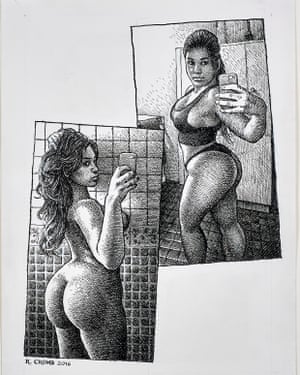

Although he mournfully insists that his work isn’t as fashionable today as it once was – to a chorus of dissent from Zwirner and Morris – he cheers up when he contemplates the upsides of the new era. Phone cameras, for instance, which allow him and Aline to “capture the commonplace” of scantily clad women waiting in cinema queues or at ice-cream stands. And selfies, “one of the technological miracles of the age we live in”.

It’s a technology that wasn’t around for the first two editions of Art & Beauty and it has given this satirist of desire, whose pneumatic women hold a warped mirror up to commercialised ideals of waiflike fashion models and muscle-bound action heroes, a whole new playpen.

In one picture, sent directly to his website, a young Latina woman photographs herself in various states of undress. The caption reports that, after listing her age, height and vital statistics, she wrote: “It would be a big pleasure to be a part of your art.” It continues: “In reply, we can only say, the pleasure is ours.” That knowing repetition of the word “pleasure” takes you straight to the little speccy guy, just out of frame, squirming with lust behind his drawing pad.

• Art & Beauty is at David Zwirner Gallery, London, until 2 June

• This article was amended on 25 April 2016 to clarify that it was with his first wife that Robert Crumb sold comics out of a baby pram.

No comments:

Post a Comment