|

| F Scott Fitzgerald |

The story behind F Scott Fitzgerald's lost short stories

Valuable insights into the troubled author’s life emerge from his meticulous scrapbooks of reviews, photographs, letters and ephemera, writes his editorFriday 17 April 2017

I

n June 2015, the trustees of the Fitzgerald estate invited me to edit a collection of F Scott Fitzgerald’s last unpublished short stories. Scribner, his publisher for his whole career, would be bringing out the book.

Since 1994, when I was a graduate student at Princeton, I have worked often with the Fitzgerald papers at Firestone Library. Fitzgerald went to Princeton in 1913 and left in 1917 without graduating, going instead straight to officer training camp to prepare to serve in the first world war. The rare books and special collections division of the library, renamed in 1948 for Fitzgerald’s college friend Harvey S Firestone, class of 1920, received Fitzgerald’s papers as a gift from his daughter Scottie in 1950. His wife Zelda’s papers were later housed there too. It is one of the most extensive, and best preserved, collections of an American writer.

I had read seven of the 18 stories included in I’d Die for You and Other Lost Stories years ago, as copies have been at Princeton since the Fitzgerald papers were donated. However, until very recently there were not enough known unpublished stories to constitute a book. In 2012, among family papers, seven more were found.

Two of the stories, though uncollected, have been published before: the screenplay “Ballet Shoes (Ballet Slippers),” printed in the Fitzgerald/Hemingway Annual in 1976; and “Thank You for the Light,” which was included in the 6 August 2012 issue of the New Yorker. In the summer of 2015, the Strand Magazine published “Temperature”, a shortened version of the story “The Women in the House”, which Fitzgerald had reluctantly revised when the long version was declined by the magazines it was sent to because of its length. He liked the long version of his Hollywood satire, and refused requests by both his longtime literary agent Harold Ober and the Saturday Evening Post, where his stories had often first appeared, to cut it any more. This full-length version is printed for the first time in the collection.

I’d Die for You and Other Lost Stories includes three screenplays that are complete, but not written as short stories. One was created on spec for George Burns and Gracie Allen; one was born of Zelda’s commitment to ballet; and one is an original idea of Fitzgerald’s, written when he was spending most of his time in Hollywood script-doctoring the work of others, or working on screenplays based on someone else’s story.

Apart from the fragment “Day Off from Love”, which shows, intimately, Fitzgerald’s creative process at work, and the completed but still in draft form “The Couple”, Fitzgerald tried to have all the stories in this collection sold, or made into movies.

He thought some of the stories in I’d Die for You were excellent, and was deeply disappointed, for personal more than financial reasons, to have them rejected by editors wanting him to write about jazz and fizz, or beautiful, cold girls and handsome, yearning boys. Fitzgerald was a professional writer from his college days, labouring over draft after draft, regularly continuing to revise on tearsheets or in his own copies of his books. By the 1930s, though, he was increasingly uncompromising about making deletions, softenings or sanitisings in his work. As Zelda wrote to a friend, years after her husband’s death, “Scott was meticulous about selling his articles and stories and never sent out anything unless he believed in it, hence, he had a right to his own judgment.”

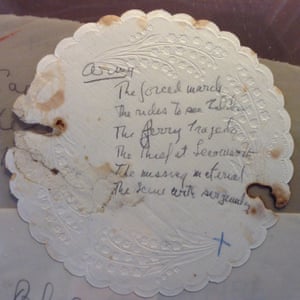

For decades, Fitzgerald kept scrapbooks (now available digitally at Princeton) of material regarding his publications, cutting out reviews and advertisements and pasting them, along with photographs, letters and ephemera, into large, black-paged books. However, he stopped making scrapbooks in the late 30s, and just kept clippings. The originals, too fragile now to use, have been copied for preservation, and references to them appear in some form in several of the stories. In “Offside Play”, for example, he mentions the celebrated NCAA champion runner William Bonthron of Princeton (1912-83), which is surely drawn from a clipping from the Princeton Alumni Weekly on Bonthron, with a perfect cigarette burn in the centre (Fitzgerald was a chain-smoker). A paper coaster, also cigarette-scarred, lists in his handwriting memories of his time in the war. Bleaker moments from his days in California can be found in clippings from the Los Angeles Times: an advertisement for a book to help someone stop drinking, tucked against a photograph of the Chrysler building – a memory of New York, the city he loved and where he wanted to be.

On a list of “7 Points of Happiness, Fitzgerald has checked off with his customary No 2 pencil the things he’s got, and circled with his red editor’s pencil those he hasn’t. This little shard of paper, and the conclusion of the article on it, tell you more about Fitzgerald than many biographical essays or film and television portrayals have managed to.

Most of the stories come from the 30s, that dark decade for him, for America and for the world. Why weren’t they published when they were written? Did Fitzgerald himself like them, and try to get them into print? What did editors think of them? What else was he doing, and what else was on his mind, as he wrote? His letters, chiefly those to Ober and to his editor at Scribner, Max Perkins, partly answer many of these questions. The archives often complete the replies. Fitzgerald remains his own best resource for anyone writing about him, his publications and his life. He saved so much, from those scribbled notes on coasters and restaurant menus to manuscript drafts of complete novels to final tearsheets – on which he often wrote further revisions and notes. In his copy of The Great Gatsby, for instance, he pencilled in changes from the dedication (adding Gertrude “Stien”) to those last remarkable, and to many readers completely perfect, paragraphs.

Without the generosity of Scottie and Zelda, both of whom insisted that his papers must be kept safely at his alma mater, all the material Fitzgerald had preserved might have been dispersed or lost. And without his own care for his literary legacy, through so many moves and travels and during such hard times, none of these stories and their drafts and backgrounds would be with us at all. Thank you, Scott.

• I’d Die for You and Other Lost Stories is published by Scribner.

No comments:

Post a Comment