|

| Child in hospital Barquisimeto, Venezuela |

'All we have are walls': crisis leaves Venezuela’s schools crumbling

Schools across the country in dire straits as teachers abandon the profession or skip the country amid one of the worst economic downturns in modern history

by Tom Phillips and Clavel Rangel in El Palmar

Saturday 15 February 2020

There are 723 pupils at the José Eduardo Sánchez Afanador school but no electricity, no computers, no tables and no chairs.

The windows lack glass, the toilets have lost their sinks and its metal classroom doors have been plundered by thieves, allowing pigeons to colonize several of the filthy spaces.

Even the school’s political director has been condemned to darkness, a tangle of wires hanging from the ceiling of her gloomy office above a portrait of South America’s liberation hero Simón Bolívar.

“It’s true, we’re facing a pretty difficult situation,” said Jetsica Benavides, as livid parents swarmed outside her door.

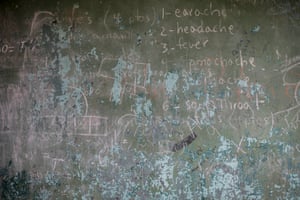

In the staff room next door the mood was bleak among teachers who said they lacked even board markers.

“All we have are the administrative staff and the teachers – and the walls,” complained one. “That’s it. Nothing else.”

The José Eduardo Sánchez Afanador school in El Palmar, a picturesque rural town 12 hours’ drive from Venezuela’s capital Caracas, is far from an aberration.

Rather, it is the perfect example of a mouldering public education system, crippled by Venezuela’s economic collapse.

Thousands of schools across this oil-rich South American nation are in similarly dire straits as pauperized teachers abandon their profession or skip the country altogether amid one of the worst economic downturns in modern history.

They leave behind students so malnourished they faint during class or fail to turn up; schools so neglected they often lack even water and electricity; and young lives put in jeopardy by the disintegration of what was once one of Latin America’s better public schooling systems.

“We’re in the subsoil. It’s a total catastrophe,” said Olga Ramos, an expert and campaigner from the Venezuelan Education Observatory project.

Ramos charted the roots of the crisis back well before the current economic slump began in 2013 and said the relentless politicization of Venezuela’s education ministry during Hugo Chávez’s Bolivarian revolution had entrusted schooling to sycophants not specialists.

But the unraveling that has played out in the last six years – since the 2014 collapse in global oil prices devastated Venezuela’s economy – has proved a knockout blow.

Activists claim as many as 120,000 teachers have left the profession in recent years, after hyperinflation rendered their salaries almost worthless.

Doris Guzmán, a teachers’ union leader in Bolívar state, where El Palmar is located, said many teachers found it more profitable to work as buhoneros (street hawkers) than give class.

Others are joining a gold rush currently gripping Bolívar or a historic exodus that has already robbed Venezuela of more than 4 million of its citizens.

Guzmán said those who remained faced a daily battle for survival; spending hours waiting for public transport to get to class; selling clothes at flea markets known as peroleros in order to eat.

“I get paid 249,000 bolívares [less than $4] per fortnight. It’s nothing,” she complained, noting that was about the same price as a kilo of meat.

“We literally do not have shoes – and I include myself in this,” added Guzmán, 56, pointing to her scruffy sandals.

Recently Guzmán suffered a finger infection while cooking and was forced to sell her clothes in order to buy the antibiotics to treat it. “It’s madness,” she said. “Complete madness.”

Venezuela’s socialist government denies its schools are in crisis.

“Venezuela remains a reference point [in education],” the education minister, Aristóbulo Istúriz, claimed last month, hitting out at what he called a foreign plot to “destroy” the Bolivarian revolution’s social achievements.

In El Palmar parents are unimpressed by such claims, and on a recent morning their fury boiled over in the quadrangle at the heart of the José Eduardo Sánchez Afanador school.

An emergency meeting - nominally called to discuss how parents might help pay for new tables and chairs – turned into a full-blown mutiny.

Inside her dingy office, the political director, Benavides, tried to rebuff criticisms that Nicolás Maduro’s Socialist party was to blame for the school’s decrepitude.

In fact, she suggested parents should shoulder some of the blame. “We all share responsibility for this situation … If this community felt the school was part of it, it would take care of it,” Benavides said.

“I’m totally optimistic,” she said, before allowing that – since the school had no resources – ending its two-year-old seating crisis would be a mid- to long-term project.

Such explanations failed to placate the parents.

Pedro García Bolívar, an evangelical preacher whose teenage daughter studies at the school, took to the stage to demand its closure.

“It’s the only solution,” he bellowed, denouncing the school’s “shameful” slide into disrepair and the mistreatment of its underpaid staff.

“We don’t have teachers here, we have slaves,” García fumed, declaring the school “a time bomb” about to explode.

Benavides emerged from her office to insist parents had no right to shutter the school.

“The only person authorized to close an institution is the Ministry of Popular Power for Education,” she declared to snorts of derision.

But Benavides was shouted down by Silvia Márquez, the school’s feisty parents’ representative.

“We’re going to close this place so the ministry comes here!” proclaimed Márquez, 37, to loud cheers and applause.

“We’re sick to the back teeth,” Márquez added waving her arms in the air furiously.

Benavides looked deflated and the parental insurgency prevailed.

Minutes later they left the school’s ramshackle campus and set off to continue their rebellion outside the town hall, shouting slogans as they marched through El Palmar’s potholed streets.

Behind them they left a school in ruins and a country’s future in doubt.

No comments:

Post a Comment