|

| Aretha Franklin |

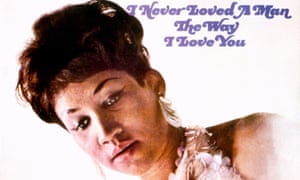

The day Aretha Franklin found her sound – and a bunch of men nearly killed it

In Muscle Shoals in 1967, the Queen of Soul recorded her first hit – despite swirling clouds of drink, jealousy and masculine competitionDavid Taylor

Sunday 19 August 2018

I

t was the tumultuous recording session in which Aretha Franklin found her voice – and a controlling bunch of men almost screwed it up.

The consequences would help define modern music, not only launching Franklin but sparking a feud in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, which started a wave of creativity that helped define music in the 1970s, bringing a stream of superstars to the cluster of four towns on the banks of the Tennessee river.

Before she was the Queen of Soul, Franklin had a false start, singing in quite a controlled way on poppy, jazzy releases for Columbia Records. Atlantic picked her up and in early 1967 sent her to FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, where a hard-charging wannabe impresario named Rick Hall had made his first No1 hit the year before. The singer of what became a soul classic, When a Man Loves a Woman, was Percy Sledge. When the song was recorded, he was working as a hospital orderly.

|

| Aretha Franklin |

Franklin, aged 24, was at a grand piano in FAME’s wood-panelled Studio A, trying to turn an idea into a song. Session man Spooner Oldham was fiddling around with a five-note riff on a Wurlitzer electronic piano.

Oldham got the intro and by the time Franklin broke loose with “You’re a no good heart-breaker / You’re a liar and you’re a cheat”, her first big hit was on the way. I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Love You) made it to No9 in the Billboard 100 and became the title track of Franklin’s breakthrough album. The raw power which made her famous was unleashed.

But in many ways, the session was an absolute disaster.

Hall died in January this year, aged 85 and widely acclaimedfor his remarkable contribution to music. In an interview in 2013, at the control desk of Studio A, he told the story of the day Aretha came to town – and the extraordinary consequences for modern music.

Hall recalled that Jerry Wexler, the legendary producer from Atlantic Records, had told him: “I got this girl, I’m thinking of signing her, I’d like to bring her down here.”

“Course, I’d never heard of her,” Hall said. “She couldn’t get arrested. She’d never had a hit record, I didn’t know whether she could have a hit record. She came in here and she had her song down and she sat at the piano here, right by the window … and played Never Loved a Man the Way I Loved You. We were immune to that. ‘What’s this song all about? It sounds like an old waltz! It’s got a waltz beat, you can’t dance to it, it’s not gonna happen.”

But he wanted Wexler’s business, so he said to himself: “We’re gonna make it happen.”

|

| Rick Hall, impresario of FAME studios, seen in 2013. Photograph: David Taylor for the Guardian |

Franklin had married at 19. Her husband, Ted White, was also her manager. They divorced the following year and a later biography suggested they often had ugly fights. Some have assumed her breakthrough song was about their troubled relationship.

Hall said: “He brought in a bottle of vodka, or sent out and got a bottle of vodka, and he began to drink and pass the bottle around to some of the horn players. Well everything was groovy until about two o’clock in the afternoon. And he started getting pretty loopy.”

White came into the studio’s console room and told Hall: “I want you to fire the trumpet player. He’s making passes at my wife.”

The trumpet player was sent home. A couple of hours later, after another complaint from White, the tenor sax was fired too.

“So tension begins to get thick in the studio and people start to get a little antsy and they know things aren’t good and they wonder what’s going on … Jerry said, ‘Let’s just call the session off.’ We’d done one song and were into the second song.”

Halfway through recording Do Right Woman, Do Right Man, the session was stopped.

“So to settle my nerves,” Hall said, “I had to have a drink or two of vodka myself and I said to Jerry, ‘I’m going over to the hotel where they’re staying and work this out. We’ll have a drink together and we’ll talk it out and everything will be fine tomorrow.’

“And he said, ‘Oh God, please don’t Rick, don’t go over there, it’ll be trouble.’

“So I went.”

Wexler was right.

Hall continued: “So I went to talk to Ted, and we came to blows. Jerry said, ‘I’m leaving this town, I’ll never come back, I’ll bury you.’ I said, ‘You can’t bury me, you’re too old.’

“So it was war from them on. I hated him and he hated me, they hated me and I hated them. It wasn’t good for the industry, it was not good for me, I made a terrible mistake going over there and getting into it with Ted, and for all that I was sorry, but you know, things happen.”

‘A very shy, introverted lady’

David Hood, a bass player who worked with Etta James, Mavis Staples, Sledge and many more, was playing trombone that day at FAME. Speaking this week, after Franklin’s death, he told the Guardian: “Working with her was one of the highlights of my career.

|

| Barry Beckett, Roger Hawkins, David Hood and Jimmy Johnson, also known as the Swampers. Photograph: Supplied for obituary |

“On that session I was part of the horn section. I’m not a great trombone player but I could do that. She was a very shy, introverted lady at the time, I think she was probably a little nervous at the start of it.”

Never Loved A Man was “kind of a strange song”, Hood said, and the session was going nowhere. But then, he said: “Spooner came up with this great little lick and everyone fell in line with that, started playing, and that saved the song. It was minutes after that we did the horn parts.

“Aretha played the piano while she sang, rather than just standing there singing. Her piano feel really helped the feel the musicians got to play with her.”

Hood recorded his part of the second song but was oblivious to the trouble.

“The rest of the guys didn’t really know what was going on. I wasn’t drinking in a recording session. You don’t go to work and drink. None of the rest of us knew about all this, we came back in the next day to start the session and there was a sign on the door saying session was cancelled.”

|

| Producer Jerry Wexler, Aretha Franklin and her husband and manager Ted White celebrate a milestone in sales, circa 1968. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives |

Wexler took Hall’s musicians to New York to finish the album, then set them up as rivals on Hall’s turf, buying a building across town at 3614 Jackson Highway, where the Muscle Shoals Sound Studio started.

Director Greg Camalier’s great documentary Muscle Shoals, the story of a small town with a big sound, has a moment when the phenomenal output of the new studio set up by guitarist Jimmy Johnson, bass player Hood and drummer Roger Hawkins is brought home. Key 1970s albums are piled up – among them Rod Stewart’s Atlantic Crossing and Bob Dylan’s Slow Train Coming.

Paul Simon, Willie Nelson and Elton John all came to record. The Rolling Stones recorded Brown Sugar and Wild Horses here, but couldn’t stay for the full Sticky Fingers album because Keith Richards was banned from the US. Lynyrd Skynyrd first recorded there – their manager gave the studio band their nickname, the Swampers. They are remembered in the lyrics to Sweet Home Alabama.

Hall, not to be outdone, did a deal with Capitol Records and turned the Osmonds into a global success.

Muscle Shoals became a music hub to rival Detroit and Memphis, having managed to start Aretha Franklin on her way.

In Studio A, the grand piano and Spooner Oldham’s Wurlitzer are still there, side by side.

FICCIONES

DE OTROS MUNDOS

PESSOA

RIMBAUD

DRAGON

No comments:

Post a Comment