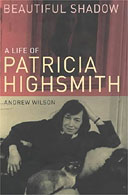

Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith

by Andrew Wilson

288pp, Bloomsbury, £25

by Andrew Wilson

288pp, Bloomsbury, £25

Patricia Highsmith's readers already know that she was a woman of many voices. She managed to produce works that are each so different it can be difficult to believe they are written by the same person. If you think that is an exaggeration, try reading her early romantic novel Carol and then her late short stories, Little Tales of Misogyny; you'll find yourself absolutely stumped as to how one person could move from such engaging charm to such vicious black humour. And both of those works have very little to do with the novels that are usually associated with Highsmith, since she made her name with sparely written suspense tales that centre on ordinary men who turn to murder - above all, the ever-intriguing Tom Ripley.

If you were looking for a single key to this diverse oeuvre, you won't find it here. This is the first biography of the writer who died in 1995, and it is a good one, stacking up oodles of anecdotes and interpretations. Perhaps it is because of its thoroughness that Highsmith remains rather elusive throughout its pages, never a simple personality, but always deeply contradictory.

This contradictoriness is partly down to the transformation that age wrought on Highsmith, as the years turned her from a sensual, romantic young woman to a solitary, disillusioned alcoholic. But there were also undeniable contradictions in the ways she was seen at any one time. Was she, as one friend says, an assured woman with a "beautiful figure, very slender, well dressed ... a certain mystique about her", or was she, as another friend said not much later, "Gauche to an extreme, really physically clumsy ... absolutely no grace"? Was she "extremely hostile and misanthropic and totally incapable of any kind of relationship", or was she "extremely good company and very generous", a "100 per cent reliable friend"?

She was American through and through, but one who hated America; she was a liberal and a racist; a lesbian with a misogynist streak. And she was never a happy woman. She moved around a lot, in the way of somebody who always finds themselves a little dislocated from their environment - from 1940s Manhattan to an English village in the 60s, provincial France in the 70s, and finally Switzerland for her last years. But wherever she went, the black dogs of her depression went with her.

She herself believed that her problems - her alcoholism, her anorexia, her feelings of inadequacy - stemmed from her childhood, and Andrew Wilson does sterling work in examining her miserable family life, with a father she didn't meet until she was 12 years old, and an eccentric mother who seemed to dislike her. "Are you a les?" her mother asked the teenage Highsmith coldly, "You are beginning to make noises like one." She went on bugging Highsmith throughout her life - in one surreal situation, she even posed as her daughter to journalists who were waiting to interview Highsmith in a hotel bar.

It is hard, as Wilson admits, to draw simple parallels between Highsmith's work and her life. After all, the most impressive thing about Highsmith's best novels is the way that they normalise extreme behaviour. In the Ripley novels and also in, say, Strangers on a Train or The Cry of the Owl, she takes you step by little step into a world where murder seems almost inevitable, almost excusable, almost ordinary, and she gives you the actions of these disaffected heroes with an almost hallucinatory clarity. It's hard to forget the vivid physical reality of Tom Ripley struggling with Greenleaf's corpse in the Mediterranean; or the gun clicking in Guy's hand in Strangers on a Train. But although Highsmith took great leaps of the imagination to produce those novels, she did undeniably share some of the sense of alienation that she gave to characters such as Tom Ripley.

When, in the 60s, an agent told her that her books did not sell well in the United States because none of the characters were likeable, she replied: "Perhaps it is because I don't like anyone." She may not have liked anyone, but she certainly loved quite a few people. She was a great lover, not just in terms of the number of women she bedded, but also in terms of the strength of her passions. She only once or twice represented such feelings directly in her fiction, and usually tended to transmute her own homosexuality into a more oblique homoeroticism of which the obsessive, doomed relationship between Tom Ripley and Dickie Greenleaf is the best example. So the insight that this book gives us into her own ability to adore and inspire adoration is intriguing and unexpected, as she moved through various lovers including out lesbians and married women.

The last time Highsmith fell violently in love - although not her last affair - was when she was 57, with an avant-garde German performance artist, and she seemed to find the pain and pleasure as keen as when she was in her 20s. But when she wasn't in the first flush of passion, Highsmith found relationships of any kind rather tricky to negotiate, and she could be deeply eccentric - deliberately setting fire to her hair at a dinner party, for instance, or inviting people to stay and giving them nothing to eat - or even downright cruel. In one chilling episode, which Wilson recounts very briefly, she coldly left the house when a girl friend threatened to take an overdose, returning to find her in a coma, then took her to hospital and again left her bedside to spend the weekend with somebody else. What's more, although Highsmith could be smitten by individual women, she gradually developed a bizarre dislike of women in general, castigating them for being physically dirty or sexually frigid.

Although her spiky, uncompromising personality may have been good for her writing, allowing her to identify with those mysterious outsiders and to keep her nose to the grindstone, it was bad for Highsmith's own happiness, that of her friends and lovers, and for her public image. The great noise of the modern publicity machine was absolutely alien to Highsmith. One scene here sums up her attitude to the whole caboodle: when she was in London in 1986, attending a dinner to celebrate (supposedly) the publication of Found in the Street, "as the evening wore on ... the noise of drunken braying grew, Highsmith ... grew ever more silent ... By the time the pudding came, she had stopped talking ... and her hands were placed firmly over her ears."

Indeed, it feels as though Highsmith never really enjoyed the fruits of her own talents. She became more and more withdrawn; one acquaintance who had to explain for the sake of Highsmith's research how to use an ATM card, commented that she had not been in the world since the 50s. But her Garbo-esque solitude did not make her happy; instead, by the end of her life everyone who met her seemed to comment on how she had the look of "someone no longer enjoying life".

To the very end she went on plugging away at her craft, even though she only occasionally, in her later years, produced anything that touched the standard of her finest work. I am wary of writers who see themselves as heroic, but there is something honestly courageous about the constant battle of her later years to keep off her destructive depression and to fill the blank pages. This is a fascinating, depressing read about a brilliant, tragic woman.

· Natasha Walter's The New Feminism is published by Virago.

No comments:

Post a Comment