|

| Jason Reynolds |

In any other year, Jason Reynolds would be travelling up and down the US visiting schools and juvenile detention centres to speak to children, sometimes at three or four locations a day. Even when the local police are angry that he’s there, or when one of the parents has connections to the Ku Klux Klan, or the school librarian has received threats for inviting him. And without fail, from the moment Reynolds enters the room, kids fall over themselves to meet the guy in jeans who will speak to them about rap and sneakers as much as the importance of reading, of being kind.

Everything about Reynolds – the bestselling books, obviously, but also the melodic, easy way he speaks and his carefully selected attire – is for the kids. “I was raised to be meticulous about my appearance,” says the 36-year-old. “But these kids, they need to know that I’m not far away – so it’s sneakers, tattoos, leather jackets, jeans, long hair, all this stuff they think is cool. And when I show up, they’re like: ‘Yo, that’s the dude who writes books?’ It can change the way they think about what it is to be an author, what it is to be literate, a bookworm, a nerd. And I take great pride in that.”

|

| Jason Reynolds |

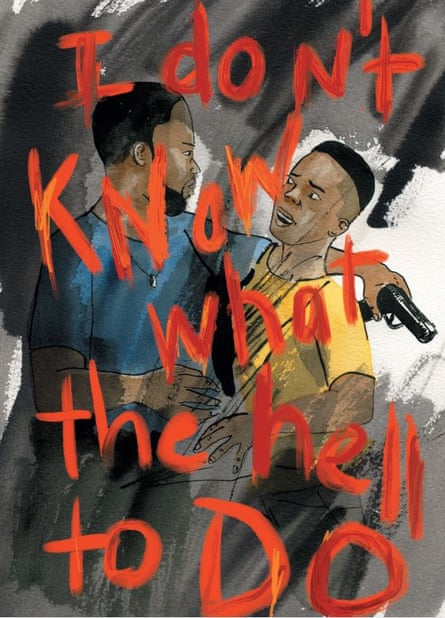

For the last few years he has published two or three books a year, landing as many spots on the bestseller lists. All American Boys, a YA novel about police violence written with author Brendan Kiely in 2015, returned to the charts after the death of George Floyd in May. Long Way Down, Reynolds’s award-winning novel-in-verse about gun violence from 2017, has just been republished as a graphic novel. Last year’s Look Both Ways was a moving and funny look at what kids get up to on the walk home from school. The four books in his Run series (Track in the US), named Ghost, Sunny, Patina and Lu for the kids on one athletics team, are all bestsellers. (Basketball player Kobe Bryant once called to thank him for writing them, as his daughter was such a fan.) And in March, working with race historian Dr Ibram X Kendi, Reynolds published Stamped, a children’s edition of Kendi’s history of racism, Stamped from the Beginning.

|

| Several of Reynolds’s books are banned in schools where some adults are offended by his unfailing directness on racism, police bias and gun violence Photograph: Quinn Russell Brown |

Several of Reynolds’s books are banned, in states where adults are offended by his unfailing directness on racism, police bias, gun violence. “But I go wherever the kids are, in the small towns, Appalachia, the heartland, Trump country. Because they read my books, too,” he says. “My friends say: ‘You can’t do that, man, it’s dangerous.’ But the children are never the problem. It’s the parents. The kids are always fun, and they’re reading the same books as kids in Brooklyn and LA. It doesn’t matter if their daddy is a racist, because their babies are reading Ghost!” he laughs. “It’s like back in the 1990s when Snoop Dogg, this weed-smoking dude from Long Beach, became a superstar. He told white folks: ‘I know you hate me. But your kids don’t.’ That’s how I feel.”

Some details of his life are well known now: the author who didn’t finish reading a book until he was 17, the poet who learned his craft through the music of Queen Latifah. But Reynolds doesn’t find either remarkable. Some children choose not to read because books are boring, and it is his job to fix that: action and drama from the get-go, told in language they enjoy. “I know that many of these book-hating boys don’t actually hate books, they hate boredom,” his website reads. “If you are reading this, and you happen to be one of these boys, first of all, you’re reading this so my master plan is already working (muahahahahahaha).”

Reynolds grew up in Maryland, Washington, the third of four children. His parents separated when he was a child and his mother Isabell “raised the whole neighbourhood” from their “hippie household”. “Everything was about manifestation. My mom was the lady with the crystals, the tarot cards, burning sage in the house,” Reynolds says. And every night before bedtime, Isabell made him recite the same incantation: “I can do anything.”

“I thought I’d be a millionaire by 25, for no other reason than I choose to,” he chuckles. “Yeah, it didn’t work that way. Life complicates things! But I was raised to believe that you can grab life by the horns and do anything you want to do.” He believes his mother was preparing him because she knew his life would be difficult. “I think she had enough men in her life who couldn’t tap into the parts of themselves that were soft, gentle or emotional. Men who were sort of apathetic and lazy, had been beaten by life to the point that they had given up trying. She wanted to make sure that we were absolutely prepared for what America would throw our way.”

When nine-year-old Reynolds discovered Queen Latifah’s Black Reign on cassette, his world was changed: words were powerful, and black artists struck him as elegant, honest and raw. He wrote a poem for his grandmother’s funeral, then began performing in bars at the age of 14. At 15, he saved up $1,000 to print 500 copies of his first collection, selling them from his mother’s car.

In his 20s, while studying English at the University of Maryland, he got an entirely different education. His father was a therapist and Reynolds became a care worker for some of his clients, helping them get food and housing, driving them to appointments. Many of them were “drug-addicted folks, formerly incarcerated folks, child molesters, rapists,” says Reynolds. “People find it is easier to compartmentalise bad people. I get it. But bad people aren’t born bad. All of us are just a life’s knock away from being that person.”

It is this understanding of humans as a pendulum, always swinging between goodness and badness, that is integral to Reynolds’s writing career, which truly kicked off with the YA novel When I Was the Greatest, published when he was 31. It is why he gets letters from children in juvenile detention centres, thanking him for understanding why they did what they did. “I’ve got letters from a kid who had caught a murder charge and he just wants me to know that he’s grateful for Long Way Down. One kid in a juvie said to me, ‘Everybody keeps telling me to change, that I need to make different decisions. But they don’t understand that every decision I’ve ever made, I thought was the right one.’ He’s not some animal. He considered his options and made the best decision he could. The onus is on adults like me to give that child more options.”

Many of the children in Reynolds’s books would be the bad kid in another author’s stories. Like Ghost in the Run books, who has bursts of anger after a traumatic event at home, and steals a pair of fancy running shoes he knows his mother couldn’t afford. Or 15-year-old Will in Long Way Down, which follows his descent in an elevator, a gun in his pocket, ready to avenge his dead brother. “Sometimes, I’ll go into a school and the teachers tell me so-and-so is a knucklehead or a troublemaker. It’s like: ‘Yo, when’s the last time you asked this kid what the matter is?’ When you pick this child as the bad kid, it means you don’t have to care any more, you don’t gotta love that child.”

Sometimes at his events, Reynolds is confronted by “the bad stuff – Klan guys, white supremacists, the angry cops who think that I’m anti-police.” Has he ever worried for his personal safety? “No. I probably should have been concerned. But like, you gonna kill me right here on the gym floor in front of these children? Are you gonna beat me? You can say whatever you want to me. Just don’t put your hands on me. But it don’t hurt me for you to call me names,” he scoffs. “You can’t call me nothing that my family members ain’t already called me.”

Reynolds appeared on many of the anti-racism reading lists produced this year, though he remains unsure of their efficacy. (“The whole world read Ta-Nehesi Coates five years ago. And so what?”) He has “complicated” feelings about the conversation around race in the US. “I am grateful for what seems to be some sort of reckoning. But I fear that ‘anti-racism’ will become another vanilla word everyone throws around and we’ll kill it because we sucked every bit of meaning from it. Because what exactly are white folk to gain in this moment? There’s got to be something, even if it’s the absolution of your own guilt. There has to be some self-interest. I’m sceptical and I have every right to be. What bit of your power and comfort are you willing to sacrifice, so the world can become more equitable?”

When we first speak, weeks before the election, Reynolds is unequivocal about voting Donald Trump out and measured about Joe Biden. “It’s interesting that we expect geriatric white men to do something new. But it’s not a time to split hairs. I got no problem with beating up on Biden – let’s get him in there first,” he says. We speak again a week after the election, and he’s pleased by the result.

“Now we have to hold him accountable. Yeah, Biden is better than what we had, but he has to remember he works for us,” he says. Biden’s decision to thank black Americans for their votes was “significant”, he thinks, “but it’s not enough to thank us for putting y’all in office and saving America again, which we always do. It is time for the value you see in us on election day to carry over on a daily basis.”

While his neighbours in Washington danced in the streets, he sat inside and enjoyed a bottle of rosé, because he couldn’t face going out during a pandemic. “I don’t want to complain too much because I’ve forged a pretty beautiful life for myself. But I’ve realised that my work is contingent upon my ability to interact with the world. I miss sitting at the bar, talking to strangers, dancing. I have terrible anxiety and I gotta put that energy somewhere or it will eat me up. Writing is always there for me. Once again, all these years later, it is saving my life.”

One of Reynolds’s favourite sayings is: “You can’t be a king without being a kingmaker”. He is acutely aware of his own legacy, of how a life can stretch beyond itself, backwards and forwards in time. Stamped was dedicated to January Hartwell, his great-great-great grandfather. “He was a slave,” Reynolds says. “He chose his own name after emancipation from words he knew: the first month of the year, and Hartwell, meaning ‘good heart’. I’m only here because of him. He somehow acquired 200 acres of land from a slave master and he built a farm in Atlanta. I grew up running around there, and now I own that land. That’s as far back as we know because the records are lost. But January is in my blood.”

Does the crown ever feel too heavy? “I’m exhausted,” he says, matter-of-factly. “But it is also an honour. These kids are my family, I gotta show up. One day I won’t be able to any more, but it is my job to make sure that someone else is there. Some of the kids that read me back when I started are in college now. I’m looking forward to the day that I read a newspaper, and someone says: ‘I grew up reading Jason Reynolds and that’s why I knew I could do this.’ Then I’ll know, I’ve done my job.”

THE GUARDIAN

No comments:

Post a Comment