Anton Chekhov: a lifetime of lovers

Chekhov's love life was complicated and very busy – he had no wish to settle down. William Boyd believes one short story reveals much about the Russian's sexual liaisons, so he wrote a play based on it

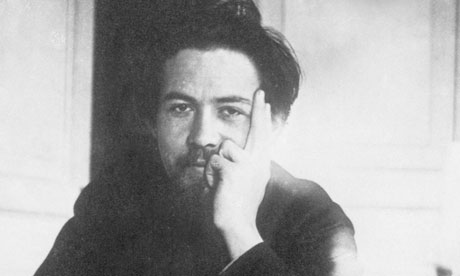

In his full, unfettered pomp ... Chekhov, photographed by his brother in 1891. Photograph: akg-images

I keep a photograph of Anton Chekhov on my mantelpiece. It's such an informal shot that it looks surprisingly modern. Chekhov appears to be sitting at a cluttered desk or a table, resting his head on his left hand. His thick hair is tousled and uncombed and his eyes look a little tired. You feel he might be about to say to the photographer, "Get a bloody move on, will you?" And indeed it's quite possible that he could have uttered such words, as we know that the photographer was his older brother, Alexander, a fact that probably explains the easy, unposed nature of the snapshot.

And we can date the photo with some precision. The Chekhov family had gathered with friends at Anton's country estate, Melikhovo, to celebrate his father Pavel's name-day. The festivities took place between the 26 and 30 June 1892. In 1892 Chekhov was 32 and entering the years of his mature fame and success. What makes the image memorable is that, because of the relaxed nature of the shot, we gain a glimpse of the private Chekhov. You can see in this casual portrait just how attractive a man he was – just what made him so appealing to women.

It's easy to forget how the portraits that emerged in the final years of Chekhov's life – the consumptive, primly dressed, prematurely aged invalid of Yalta – have come to dominate our sense of the writer. Chekhov was tall for the late 19th-century, six foot one, a big man. Looking at him in this photo, in his early 30s, somewhat dishevelled, candid, at ease, you can gain some idea of what it might have been like to meet him when he was in his prime, in his full, unfettered pomp.

The more you learn about Chekhov, as you read biographies, memoirs, the letters – the more clear it becomes that he led a love-life of astonishing activity and complexity. Chekhov, it turns out, had a great many affairs, some enduring several years, and most of the women involved with him for any length of time wanted to marry him. I was curious to know if any precise tally of his lovers had ever been made and, not finding one, I asked Donald Rayfield, author of Anton Chekhov: a Life (indubitably the best biography of Chekhov ever written), to try to draw up as accurate a list of names as possible.

The scrupulously made list that emerged is based solely on documented evidence. Some 33 women are actually named (there are a few anonymous encounters). The effect of identifying the women in Chekhov's life is powerfully revelatory: his love affairs become suddenly more real and a different Chekhov emerges. We can now claim to have as full a sense of his amorous life as can be realistically quantified. It starts in 1873, when the teenage Chekhov visited a brothel in his home town of Taganrog and continues until 1898 when his relationship with the actress Olga Knipper began. Chekhov was then in ill health, and eventually married Knipper in 1901. The picture that emerges is of a man who, over the course of a couple of decades, enjoyed at least two-dozen love affairs of varying intensity – some extremely passionate, some casual, some lasting many years, and some that were clearly going on simultaneously – and who, it's also clear from his letters, continued to be a regular visitor to brothels in Russia and elsewhere in Europe.

What is one to make of this information, and to what extent is it only part of the story? What relationships have we missed, perhaps, that weren't referred to in correspondence? Does it mean that we see Chekhov as a kind of literary Don Juan – or is it, more interestingly, a reflection of the relaxed sexual mores that prevailed in middle-class intellectual circles in the last decades of the 19th century in Russia? By 1898 Chekhov's health was seriously impaired by his tuberculosis, and he had only six more years of life left; he died at the early age of 44.

He was the most private of men, yet he preserved, annotated and filed away his correspondence with an archivist's zeal – hence our ability to present this inventory of his love life. My own interest in Chekhov's love affairs was stimulated by a particular short story Chekhov wrote, called "A Visit to Friends". I've used this story as a key source of a play, stitching it together with parts of another story, "My Life", to form a dual adaptation that I've entitled Longing. "A Visit to Friends" is intriguing because it was written in 1897 while Chekhov was convalescing in Nice, escaping the Russian winter for the good of his ravaged lungs. It's a great, mature short story – containing, among other things, the germ ofThe Cherry Orchard in just over a dozen pages – but, mystifyingly, Chekhov didn't include it in his collected works and it is consequently the least translated of the great stories of the last decade of his life. It's as if he didn't want it acknowledged – as if he preferred it were kept out of view, excluded from the canon.

There are various theories as to why this might be. One is that Chekhov didn't like writing his fiction outside Russia and therefore didn't feel the same about it; or that, being abroad, he didn't have a chance to see proper proofs and therefore regarded it as not properly finished. But my own hunch is that in "A Visit to Friends" we may have a rare self-portrait of the author himself in the character of Podgorin, the protagonist, a Moscow lawyer, whom I've called Kolia in my play.

Kolia, like Chekhov, is someone women find very attractive and again, like Chekhov, Kolia finds it emotionally impossible to commit to marriage or even an enduring relationship. Two women – an old lover and a beautiful young girl – yearn with quiet desperation for Kolia's love, and it is not finally forthcoming. In the story – and the play – Kolia always prefers to sidestep or ignore rather than confront raw and powerful emotions. Tactically, he feels that evasion is better than any kind of heartfelt vow or undertaking any kind of serious sentimental responsibility.

I wonder if Chekhov suppressed this story because he sensed that the many women in his life would recognise in Podgorin something familiar – the charting of a faltering emotional course known all too well to them, and might see it almost as a kind of explanation or apology, if not a confession. Chekhov's greatest friend, the newspaper editor Aleksey Suvorin, described him, most revealingly, as a "man of flint … he's spoilt, his amour‑propre is enormous". In "A Visit to Friends" Chekhov, this man of flint, perhaps let his guard drop for once – it's very hard to find anything resembling autobiographical portraits in his work – possibly because he was ill and was far from home.

In any event, there's no doubt that in Podgorin/Kolia we see a fascinating simulacrum of the Chekhovian love‑life. Chekhov loved women and their company – and he clearly loved making love to them, as the number of his sexual liaisons demonstrates – but in all his relationships he began to cool and draw away, just as they were reaching a point of amatory heat that implied something more lasting and intense.

His most ardent affair, I believe, was with a young woman called Lika Mizinova. Mizinova was 19 when Chekhov met her in 1889 (he was 10 years older). She was a friend of his sister and a young schoolteacher who had dreams of becoming an opera singer. She was ash-blond, a chain-smoker, buxom and sexy and she and Chekhov had a rollercoaster on-off affair that endured almost 10 years before the Chekhovian chill became intolerable and the possibility of marriage retreated over the horizon. However, while it was on it was clearly both great fun and very passionate. Chekhov and Mizinova's correspondence is copious and highly indiscreet.

There are 98 letters surviving from Mizinova to Chekhov and 67 in the other direction. The tone is candid and mocking, almost derisory, as they each have a go at the other, revealing the erotic subtext beneath the charged banter, as if the letters themselves were designed to provide some sort of sexual frisson. Mizinova wanted marriage, but eventually realised that, for Chekhov, lasting mutual happiness was either something he didn't believe in or saw as too great a threat to his freedom. Too much would have to be given up. One recalls Suvorin again: "he's spoilt".

A photograph of Mizinova and Chekhov at the end of their protracted dalliance in 1897 shows that she has put on weight. She looks and leans towards him but Chekhov is almost visibly recoiling, his body-language eloquent – canted away from her, his eyes elsewhere, legs crossed, hands clasped tightly over his knee, his face almost pinched in its hardness, its refusal to yield.

Character is destiny, they say, and perhaps Suvorin saw in Chekhov's character his mighty resolve and dedication to the Chekhov project. "Enormous amour-propre" leaves little room for any other kind of amour, anyway. But there is another reason that might explain both Chekhov's emotional appetite and his stubborn refusal to make that final commitment to another person. Chekhov was a doctor; he had his first major lung haemorrhage in 1884 so he knew what was wrong with him. Many members of his family and friends had died of tuberculosis, so there could be little uncertainty about the fate that awaited him also. Under such circumstances, knowing that his life would be short, perhaps Chekhov felt it was more honest not to encourage ideas of a lasting union. And yet, he did get married at the end of his life – to Olga Knipper. It was not a particularly happy marriage – they spent huge tracts of time apart: Olga needed to be in Moscow for her stage career while Chekhov's failing health required him to stay in the warm south – and there is strong evidence that Olga had affairs with other men while Chekhov languished in Yalta. But by then he was chronically ill and any self-reflecting ruefulness he might have indulged in about his late matrimonial urge would have been pointless. Olga stuck with him and was present at his death. She did commit, in her own way.

No comments:

Post a Comment