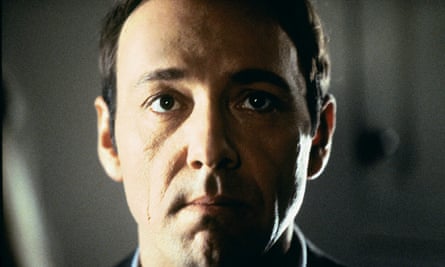

Jonathan Yeo portrait of Kevin Spacey as Richard III, 2013. Photograph: Jonathan Yeo/

How Kevin Spacey brought Hollywood to the West End

Kevin Spacey once met Laurence Olivier. “I was a Juilliard student at the time. I met him in a hallway. I was very nervous,” he divulged during a Guardian webchat last year. If there’s more to the anecdote, we’re unlikely to get it out of an actor so notoriously tight-lipped that it was once remarked: “We know more about the surface of Mars tihan we do about Kevin Spacey’s private life.” But the encounter is an intriguing prospect. Did they talk? Did irascible old Olivier offer advice, or brusquely shove Spacey out of his way? In the biopic version of the scene, their eyes would meet with a glimmer of fateful recognition as they passed in opposite directions.

There is an affinity, after all. Both men are candidates for greatest actor of their respective generations, and both have been instrumental in reviving the fortunes of London’s Old Vic theatre, as artistic directors as well as actors. But while the trail from the West End stage to the Hollywood screen is extremely well-trodden by British actors (Olivier helped blaze it), it’s extremely rare that they pass anyone coming the other way.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Spacey had Hollywood at his feet. He’d starred in some of the key films of the 1990s – American Beauty, The Usual Suspects, LA Confidential, Se7en – and won two Oscars for his labours. He could have settled into a comfortable, De Niro-esque middle age of comedies, cameos and superhero movies, but instead he took on fresh challenges in other media: first British theatre, then the internet. Admittedly there was the odd superhero movie, too (he played Lex Luthor in Bryan Singer’s Superman reboot in 2006), but it was still an astounding move. “I’m trying to do something with my success which is bigger than myself,” Spacey said at the time. “I’m no longer interested in my personal career.”

It goes without saying both gambles have paid off handsomely. Web-streaming service Netflix took a substantial risk by moving into original content, but its Spacey-led flagship, House Of Cards, has been a triumph. The political drama is now on its third season, and Spacey’s smooth-drawling, delectably amoral congressman Frank Underwood is on the verge of becoming pop culture’s next great antihero. As one reviewer put it: “[Breaking Bad’s] Walter White was bad, but Underwood is evil.”

Meanwhile, London’s theatre community is preparing to thank Spacey, 55, with a special Olivier Award next month for his transformation of the Old Vic, plus a gala celebration in Spacey’s honour with tributes from the great and good, performances from Annie Lennox and Sting, and “premium tickets” for £2,000 each.

It is a triumphant finish to a tenure that got off to a very shaky start. When Spacey was announced as artistic director in 2003, it was widely assumed this was a vanity project of which he would soon tire. “The first season was pretty mediocre, to be honest,” remembers Michael Billington, the Guardian’s theatre critic. “The play choices weren’t all that good [Spacey’s first production, Cloaca, by Dutch writer Maria Goos, was indifferently received]. What we really wanted was the big stuff: Shakespeare, O’Neill –not so-so comedies.” Billington recalls Spacey inviting him to lunch around that time to put across his point of view: “He said: ‘I’m here for the duration. I’m not going to give in. I’m going to make this thing work.’ I found him very likeable but I could also sense the steel there.” Billington also felt the steel in Spacey’s handshake, “one of the hardest I’ve ever had”.

Spacey did provide “the big stuff” at the Old Vic, starting in 2005 with his own portrayal of Richard II, his first major Shakespeare role. His tirelessness impressed them all, says actor Julian Glover, who played John of Gaunt in the production. “He’d been in America the day before we started so he must have been heavily jet-lagged, but he was absolutely, completely on the ball at the first reading. We could have understood if he’d been a little grey but he just wasn’t. And he kept on improving and improving. He never stopped working at it. I have nothing but praise for him.”

It is no surprise London’s theatre world adores Spacey. The Old Vic was due to become a strip club or a carpet warehouse before he took over. As promised, Spacey used his star power to lure other A-listers on to its stage: Jeff Goldblum, Ethan Hawke, Richard Dreyfuss, Sex and the City’s Kim Cattrall, not forgetting British stalwarts such as Vanessa Redgrave, and Ian McKellen – who memorably played Widow Twankey in Aladdin. But Spacey also modelled the Old Vic like a publicly funded institution, which it is not. He insisted on cheap seats for young people, initiated youth talent and education schemes, and brought in substantial donations. It was youthful, vibrant and relevant again.

Spacey has not given up the day job, either. He stars in many of its productions – invariably to great acclaim. He has also been filming House of Cards for six months a year, taking the odd Hollywood role and executive-producing movies such as the Social Network and Captain Phillips. Oh, and he sings with a 40-piece band from time to time. He’s widely read, politically engaged, a great raconteur and impressionist, and has powerful friends, from Bill Clinton to Elton John to Peter Mandelson. He’s more Superman than Lex Luthor.

That drive and momentum seems to have been with there from the start. Growing up in Los Angeles, he was apparently a wayward child, though an early attempt to discipline him at military school backfired when he was expelled for fighting. He also quit Los Angeles Valley College to study drama at New York’s Julliard School (on the advice of his classmate Val Kilmer), having got the acting bug in high school. But then he quit Julliard after two years, impatient to get to work. He engineered his own big break by blagging an invitation to a cocktail party and persuading director Jonathan Miller to audition him for his Broadway version of A Long Day’s Journey Into Night, opposite his hero Jack Lemmon.

“Is he different from other people? Yes he is,” says Thea Sharrock, director of Clarence Darrow, Spacey’s current one-man play at the Old Vic. “He’s an absolute dream to direct because he’s incredibly quick and very, very thorough. He thinks everything through and is often 10 steps ahead. Which is why on stage he’s so alive and so dextrous. He wants to go to the edge every time, but he’s not a thrill-seeker in that sense because he does it with serious hard work and preparation behind him. He’ll never fall; he’s just teetering. That’s where the danger and the excitement comes from and he knows it, and he is willing to go to that place in order for the audience to be entertained in the best way possible.”

“He’s a very fine actor in tragedy but I think he’s a born comedian,” says Michael Billington, pointing out Spacey once attempted to become a stand-up comic. “He has a natural comic instinct, and that’s true of many great actors. Laurence Olivier’s instincts were fundamentally comic. Great actors often look for the ironic subtext in a role.”

On stage or on screen, Spacey has a talent for making unlikeable characters likeable, none more so than his celebrated Richard III, in Sam Mendes’s 2011 production. It’s one of the juiciest roles in drama, but Spacey put his stamp on it, with modern military uniform, a leg brace and his inexhaustible energy. “He had no qualms at all about being evil,” says Julian Glover. “He didn’t try to pretend Richard was a nice bloke really. Not at all. He was an absolute, absolute first-rate arsehole from beginning to end, and it was wonderful to watch.”

There’s more than a touch of Richard III in Frank Underwood, Spacey’s Machiavellian schemer in House Of Cards. Again, he gets the audience on-side by addressing them directly, making them complicit in his ruthless backstabbing and injecting sly humour into his otherwise atrocious conduct. In both instances, Spacey makes us aware of the performance within the performance. It’s a quality many of his best roles share, from the deceptively sharp Verbal Kint in the Usual Suspects to American Beauty’s Lester Burnham, who takes glee in refusing to play his allotted role any longer, or Clarence Darrow, for whom the courtroom is a stage within a stage. Straightforward doesn’t suit him.

Can the man of steel do no wrong? The only time we’ve seen seen another side to Spacey is when his privacy has been threatened. Asked by Metro why he made a documentary of his world tour of Richard III last year, he responded: “I don’t know. You’re right, maybe we shouldn’t have. Why fucking bother? I can’t justify it. Wanted to do it. Did it. I hope people enjoy it, if they don’t, don’t watch it.” Was that the famous Spacey charm slipping, or had the jet lag finally got to him?

What next for Spacey? It seems like he could go in any direction: stage, small screen or big screen. He quits the Old Vic in autumn but has no plans to leave London, apparently. There’s a fourth season of House Of Cards next year, and he’s just finished a movie in which he plays Richard Nixon – a delectable prospect. Last year he told the Guardian he’d like to do a musical.

“I think he’ll carry on doing what he’s always done which is look for the next exciting opportunity that comes his way,” says Thea Sharrock. “He never went looking for the Old Vic. To a degree it presented itself to him. It felt right and he ran with it. Same thing with House of Cards. He just had a hunch this was worth taking a risk on. His curiosity is such a defining characteristic of him. He sees doors where other people don’t.”

The Kevin Spacey CV

Age 55

Career Came to attention in the Broadway version of A Long Day’s Journey Into Night, opposite Jack Lemmon in 1986. Won a Tony award for Neil Simon’s Lost In Yonkers in 1991. Film roles include Glengarry Glen Ross (1992), Se7en (1995), The Usual Suspects (1996), LA Confidential (1997), American Beauty (2000) and Superman Returns (2006). Artistic director of The Old Vic since 2003. Lead role in House of Cards on Netflix.

High point Won best supporting actor Oscar for The Usual Suspects, and Best Actor Oscar and Bafta for American Beauty. Won Golden Globe for House of Cards in 2015.

Low point His first year at the Old Vic was greeted with scepticism.

He says “If there is one thing I object to it’s actors talking about how tough their jobs are. My job is a joy.”

They say “There’s the dramatising of a text and then there’s the seduction of an audience, his skillset in both of those things is unparalleled, but there’s another aspect to Kevin: he knows what it is to be the leader of a company. He’s much more like a co-director.” David Fincher

No comments:

Post a Comment