Beautiful and brutal: how James Salter set the standard for erotic writing

Following a young couple in 1960s France, A Sport and a Pastime asks how we make sense of romance and tells the truth about sexual love

Friday 17 February 2017 13.00 GMT

“I

am not telling the truth about Dean,” the unnamed narrator warns the reader early in A Sport and a Pastime. “I am creating him out of my own inadequacies, you must always remember that.” So begins an ardent, interruptive tale of desire and discovery, conceived self-consciously and sensually on each page.

Since its publication in 1967, during the decade of sexual revolution, A Sport and a Pastime has set the standard not only for eroticism in fiction, but for the principal organ of literature – the imagination. What appears at first to be a short, tragic novel about a love affair in France is in fact an ambitious, refractive inquiry into the nature and meaning of storytelling, and the reasons we are compelled to invent, in particular, romances. That such a feat occurs across a mere 200 pages is breathtaking, and though its narrative choreography seems simple, the novel is anything but minor.

The narrator is staying in the house of rich friends in Autun, Burgundy, idly photographing the town and trying to uncork provincial culture. Thwarted in his own sexual yearning, he becomes obsessed with the relationship between his fellow guest, a nomadic American dropout, Philip Dean, and a local girl, Anne-Marie. Our narrator is the perfect voyeur, entirely suited to observation and vicariousness, and although not directly engaged in a menage a trois, his agency is crucial.

One cannot introduce the work of James Salter without mentioning his unmistakable prose. By this, his third novel, he had become the greatest stylist of any contemporary writer. There are sentences so precise, so abrupt and absolute, they almost defeat style, like literary pointillism. His evocations are both intricately faceted and vastly dimensional – a France of weather and architecture, history, flavour inhabited by characters as familiar, contrary, seasoned and unknowable as any human can be. Choose a page:

This blue, indolent town. Its cats. Its pale sky. The empty sky of morning, drained and pure. Its deep cloven streets. Its narrow courts, the faint rotten odour within, orange peels lying in the corners.

Another page:

Sometimes he is depressed by her imperfections. They should not be important, perhaps, but they often become so real, so ready to take control of her, these plain qualities hidden by the brilliance of a language and life the taste of which he has only just begun to grasp. He waits for her to put on her coat. She avoids his eyes.

Material, craft, and affect: Salter had a poet’s sense of aspect and essence, with power sustained across the long-form. Every sentence seems exactly right, each proposal true. The conceit of a work of fiction is to hide its mechanisms, to simulate, to suspend, even if it plays tricks with exposure and the seductiveness of words. The reader must be willingly transported into the believable unreal, as here the narrator is transported, via the erogenous imagination, deep into the heart of carnality and blinding emotion. Salter’s any-man narrator is complicit in our knowledge of the lie and understands the necessity of fabrication; a witness and an agent provocateur within his own story, he is also the reader’s accomplice.

Though Anne-Marie is the object of his desire and the subject of his incandescent, burning dreams, it is Dean he fixates upon. Dean is the sexual avatar, confident and entitled. He arrives at the house in Autun as heroes do, with ragged elan. He drives a discontinued Delage, a car flamboyantly at odds with the common Citroëns and trains of the nation, and sets about his regional conquest, plundering “the real France”, as he plunders Anne-Marie.

Dean’s physicality, his form, is as vital and compelling as Anne-Marie’s, and is rendered with equal care and attention by the narrator. We come to know his body thoroughly, as an attentive partner might. There are sublimated notes of homoeroticism in the text, jealousies and elaborations. The narrator is haunted, not just by a girl he cannot possess, but by another man’s prowess, his ability to perform. Even as he contemplates the eligible divorcees of the town for his own satisfactions, he remains passive, perhaps neuter, a receptor for the lust of others. “I am only putting down details which entered me, fragments that were able to part my flesh.”

Like Nick Carraway towards Gatsby in The Great Gatsby, this narrator’s ambivalence towards the winning, self-created character of Philip Dean is rounded by admiration. Their power differential is stark and paves the course for the obsession. “I am only the servant of life. He is an inhabitant.” The narrator wishes to know France: he observes France, catalogues her by eye and by lens, and he speaks the language, but it is Dean who journeys and surveys; who penetrates the culture. Dean takes a lover without promise or reciprocity; he takes her for whatever he can get now, like a colonial. He is penniless and directionless, has quit Yale, where “everything was too easy”, and is dependent on a rich father, on his charms and looks, to maintain his sexual flânerie and hotel tours. Dean’s fate is part of the attraction – it’s exciting but clouded, which will enable him to be a living idol, and to survive his betrayal, just.

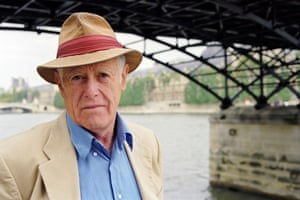

Photograph by Ulf Andersen

But who is Anne-Marie? She’s a shop girl, though a cut above: alluring, commanding, sacred and temporary. She is youth, if not innocence. She has a “stunning sexuality, but it’s like memorising the reflections of a diamond. The slightest movement and an entirely different brilliance appears.” The source of her power is rare, and also commonplace. She is chosen, she arrives, she’s a rapturous illusion – in the end it doesn’t matter. Like many women, and the shrewdest psychologists, Anne-Marie will come to understand that we can “die of love”. Only 18 years old when the affair begins, she’s already had previous lovers – a black American soldier, an Italian waiter. She is both unschooled and willing, that heady mix, and as such she is the novel’s erotic accelerant. Submission, control, preference for positions and role-play; she’s an actor in the theatre of intimacy, gazed upon, reactive and adored. She will be educated and will experiment with technique and methods, both painful and pleasurable; she will be humiliated, used, abandoned, as she will also be gloried in, raised up as a goddess, immortalised.

And this transaction is, of course, the truth about sexual love. It’s a gorgeous minefield. Gender politics and sexual powers are coolly tested throughout the novel – another of Salter’s remarkable skills – and are revealed to be inadequate analyses. Male solipsism. Female sentimentality. The labels stick and then peel off. Lovers are cruel and selfish, as well as generous and collaborative; they are imbalanced emotionally even if they match physically. Lovers pine and fantasise and self-deceive, they profess, they lie, they leave and they remain indelible to each other’s lives. Salter understood what lies beneath housebroken relations and rules: the fairytales. He understood the deregulation of encounter and exchange – beginnings and endings, potency and vulnerability, the construction of a union and its breaking points, moments of genuine affection and failure of feeling. In this brutal and beautiful novel, nothing is reconstituted to save our feelings. It’s all presented with gratuitous honesty.

Students of literary passion owe the author a huge debt. We’re not benign creatures in love, but angels of pornography. Nor are the mechanics of sex immune from attachments. To be privy to Dean and Anne-Marie’s entanglement is to look in on our own private, impure bedrooms, our own desires and crimes.

How compulsive and how fascinating. Until the last page, the book’s tension is exquisitely drawn. Though impotent, the narrator details everything, lays it bare. He activates the grand romance that Dean himself seems incapable of. Perhaps he is Dean, Dean’s higher, missing component. Or Dean is the alter ego, granting permission, enabling wish-fulfilment of the constrained libido. In this domain, we have so many selves.

Certainly the narrator is our registrar – without him nothing of the relationship is notarised; nothing can really exist. His observations and judgments are as cruel as they are tender – Anne‑Marie’s bad breath, her lack of intelligence and peasant’s earlobes. Her expectations of marriage are foolish and perfectly reasonable. Dean is callow and handsome, he stimulates and elates his lover, but he is terrified of the consequences, responsibilities, babies. He fails to respect France and her regulations, and he calculates, on a base level, that money and happiness are bedfellows. Together, the couple’s “atrocities induce them towards love”.

But what is love, the novel asks? What can it be, beyond temporal, beyond other? Is it simply the conceit of art, like the songs on Anne-Marie’s little plastic radio? Is it the impossible phenomenology of someone else’s account? A thing unreal to our selves, frigid under our own hands, lambent only when dreamed? Is love just a story, created from our biological urges and our soul’s ache, so that we might make sense, somehow, of our coming together, our making of it, and our parting?

• James Salter’s A Sport and a Pastime is published as a Picador Classic.

THE GUARDIAN

DRAGON

Sarah Hall / ‘I love writing about sex, the civil veneer stripped off’

2002

2010

2013

2017

Beautiful and brutal / How James Salter set the standard for erotic writing

School of hard knocks / The dark underside to boarding school books

Rereading / Primo Levi’s If This is a Man at 70

Studs Terkel’s Working / New jobs, same need for meaning

My Cousin Rachel / Daphne du Maurier's take on the sinister power of sex

Beautiful and brutal / How James Salter set the standard for erotic writing

School of hard knocks / The dark underside to boarding school books

Rereading / Primo Levi’s If This is a Man at 70

Studs Terkel’s Working / New jobs, same need for meaning

My Cousin Rachel / Daphne du Maurier's take on the sinister power of sex

No comments:

Post a Comment