|

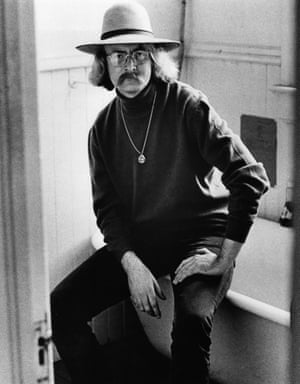

| Cat in a hat … Richard Brautigan. Photograph by Chris Felver |

The brilliance of Richard Brautigan

Fairytale meets beat meets counterculture: bursting with colour, humour and imagery, Brautigan’s virtuoso prose is rooted in his rural past – and that’s what draws me in

Sarah Hall

Tuesday 23 September 2014 15.24 BST

Over the years, I’ve lived in a variety of places, including America, but I was born and raised in the Lake District, in Cumbria. Growing up in that rural, sodden, mountainous county has shaped my brain, perhaps even my temperament. It’s also influenced the qualities I seek in literature, as both reader and writer. In my early 20s, connecting with fiction was a difficult process. There seemed to be little rhyme or reason to what was meaningful, what convinced, and what made sense. There was a lot of fiction I did not enjoy, whose landscapes seemed bland and unevocative, the characters faint-hearted within them, the very words lacking vibrancy. This was no doubt empathetic deficiency on my part. I wouldn’t say it was lack of imagination – if anything, roaming around moors and waterways solo can lead to an excessive amount of making things up, a bizarreness of mind. I suppose what I wanted to discover was writing that served these functions, and I was in danger of quitting books.

Around this age I first read Richard Brautigan. When I learned that he was from the Pacific Northwest – an equally wet, rustic, upper corner of America – the coordinates struck me as significant, I sensed a geographical cousin. True enough: this formative territory is carried within his work, not as romantic vastification, but a sort of regional echo, possession of an underlying spirit. Though Brautigan moved to California, wrote about California, and California’s hip, sexy, psychedelic tropes become superimposed on his writing, beneath the berserker elements there remains trickling sadness, a wide-open loneliness, psychological rain. Such sensibility might partly be personal or social – the poverty of his youth and, later, mental illness. But its roots are perhaps Oregonian. In his collection of short fiction, Revenge of the Lawn, Brautigan describes the Pacific Northwest as, “a haunted land, where nature dances the minuet with people and danced with me in those old bygone days”. The stories set in this territory, about hunting and fishing, childhood play and damp weather, display a kind of sobriety and straightness that the San Francisco tales often don’t; the narrator is an isolated self, on a bridge, up a river, hitchhiking home in a soaked coat. Though these pieces aren’t necessarily bound by conventional physics or literary laws, something earnest and “real” rises to the surface in them, like trout in the author’s lost forest streams.

And then there are the stories where reality bends and warps, stories that seem to explode off the page. It’s also true that in my early 20s I was looking for prose with big personality – vivification and invention. Brautigan is a high stylist; his lines can be astonishing and have neon-grade memorability … “I sounded as if I had stepped in a wheelbarrow-sized pile of steaming dragon shit” … “she opened her purse which was like a small autumn field and near the fallen branches of an old apple tree, she found her keys” … “The way he lit a cigar was like an act of history.” But it’s very hard to label his work. Fairytale meets beat meets counterculture? Surrealism meets folk meets scat? The writing is bursting with colour, humour and imagery, mental flights of fancy, crazed and lurid details. There are wild inaccuracies and fever-dream occurrences. Bees living in hives made of liver. Bears dressed in nightgowns. Whisky-drinking geese. Heartbroken friends set fire to radios and the lovesongs being played melt into each other. People pay 237 cheques into the bank at once while the narrator waits, thinking of the skeleton buried in his garden holding a can of “rustdust” money. Men in debt have the shadows of giant birds attached to them.

Richard Brautigan

San Francisco, 1970

Photograph by Michael Ochs

The more you read, the less there seem to be regulations and governing forces, ways of qualifying Brautigan. The mind of the author is simply too unbound, too childlike in its enormous, regenerative capacity to imagine. I often give one of his short stories, such as Homage to the San Francisco YMCA, to a creative writing student on the first day of a course. Suspecting I want them to write like Balzac or Woolf, the relief on their face is palpable. Not just relief, but sheer delight. Plumbing replaced by poetry! A man forced out of his own home by John Donne’s sonnets, Emily Dickinson, Vladimir Mayakovsky, et al! Many creative writing lessons are pointless, but this one is not. Even in adulthood, and no matter our circumstances, the imagination is a phenomenally powerful device, perhaps the most powerful. Brautigan knew it; he was a master-practitioner, a high-wire act.

Though he did occasionally fall. His metaphors can be widely off the mark, some too gnomic to comprehend. Where the brutally brief length of The Scarlatti Tilt makes it one of the best flash fictions ever written, other pieces feel boil-in-the-bag, or half-formed, more musings than anything else. A feminist Brautigan was not – women often occupy wistful sexual and aesthetic space only in the tales, are expected to get on board with men’s desires, be compliant when a character wants to get laid. He does better with old ladies and daughters, where the complicated business of sex is moot. Here there are acute character studies and even heroines. Possibly the wisest person in the entire collection is the little girl in A Short History of Religion in California, who rejects the piece of cake given to her by a christian in the campsite where she is staying with her father. “I’ve already had breakfast”, she explains. She’s previously expressed a desire to be a deer, to have antlers and hooves, which, in the scheme of the story, makes perfect metaphysical sense.

If you think things work a certain way, think again, Brautigan’s stories encourage, and quite rapidly the reader does forget the normal arrangements. The shifting perspectives and playful reversals, the activation of inanimate objects, the sudden sentience of things we believe to be unthinking, the unusual possibilities of life, in the end might provide some consolation for the fact of Brautigan’s tragic death and the lessening of interest in his work over the years. “Perhaps the words remember me”, he writes in Banners of My Own Choosing, as if there is, or could be, a world where the letters and sentences produced by an author are capable of nostalgia, even affection. I love this idea.

Certainly the words in Revenge do justice to the writer. Perhaps because I first read him when young and those associations remain, when I go back to Brautigan I half-expect the naive and imperfect aspects to disappoint. I’m never disappointed. Those same virtuoso characteristics of limitless creativity, the lambent glowing of the old country and the iconoclastic energy of the period, shine through. It still rains evocatively over the woods and valleys of the Pacific Northwest. The quotidian and the impossible walk hand in hand. There’s exceptional originality and levity to the phrasemaking. I’m reminded of the fundamental qualities I sought out in literature, connections that were so vital at the time, and still resonate now.

• Sarah Hall’s short-story collection The Beautiful Indifference is published by Faber.

No comments:

Post a Comment