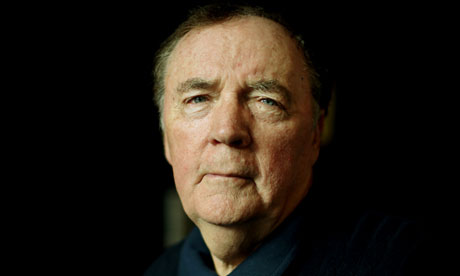

'So many thrillers don’t work because you don’t care about the characters or the situation' … James Patterson. Photograph: Graeme Robertson for the Guardian

Eyebrows were raised a few weeks ago when a series of full-page ads appeared in the New York Times Book Review, Publishers Weekly and elsewhere in the US literary press, asking "Who will save our books? Our bookstores? Our libraries?" Thirty-eight great American books, fiction and non-fiction, were cited as examples of work that might have been lost without vibrant publishing and bookselling industries and cultures: from William Faulkner to Junot Díaz; Norman Mailer to Joan Didion; Thomas Pynchon to Art Spiegelman. The ad concluded by comparing the federal bailouts of the banking and car sectors to the neglect of books. Striking stuff, but it was not so much the sentiments expressed that caused surprise, as the signature at the bottom of the man who had paid for and written them: James Patterson.

In fact Patterson is familiar with deploying the power of advertising – he is a former chairman of agency J Walter Thompson – and in recent years he has been an outspoken advocate for books and child literacy. But most of all his intervention fits with a career that has not only seen him become one of the world's biggest-selling authors, but also one who has in the process revolutionised the popular book market.

Speaking to Publishers Weekly, Patterson straightforwardly explained his motivations: "I like to do things." His complaint was: "Publishers are sitting around saying: 'Woe is me.'" His advice: "Get in attack mode." This approach has helped him publish more than 100 books and sell approaching 300m copies. As long ago as 2006 his work passed $1bn in gross income and in recent years, in which he has topped the Forbes list of highest-paid authors, his earnings have been estimated at $80m-$100m a year. It has made him famous enough to appear as a character on The Simpsons, and more intriguingly, his marketing strategies have been the subject of a Harvard Business School study.

It was Patterson who first showed that television advertising could work for books. More radically, he has demonstrated that working with co‑writers can dramatically multiply sales. While he continues to write solo his books featuring Alex Cross – the black, single‑parent, Washington DC detective and psychologist, who first brought Patterson to a mass audience – he generally works with named collaborators on other bestselling series such as the Women's Murder Club (San Francisco cop, lawyer, doctor and journalist who combine to solve crimes) and the Michael Bennett series featuring a New York widower detective with 10 adopted children. Alongside these and the other thrillers, Patterson's oeuvre is expanding at the rate of 10 books a year and also takes in romance stories and, increasingly, books for young adults.

"My short answer to the question as to why work with other people is Gilbert and Sullivan, Rodgers and Hammerstein, Woodward and Bernstein, Lennon and McCartney and it goes on," he says. "There is a lot to be said for collaboration and it should be seen as just another way to do things as it is in other forms of writing, such as for television, where it is standard practice." But back in 2000 – he had by then written five Alex Cross books (his 21st is out this autumn) – when he suggested publishing multiple books in a single year his publishers were initially aghast.

"They wanted one hardback and one paperback a year. I had ideas for an Alex Cross, a standalone thriller and a romantic novel. My publishers weren't comfortable with the romance because it wasn't my brand. So I gave them my idea of what a brand is: a connection to someone or some product, from which people can expect something. With my books people expect the pages will turn. They'll know the difference between what looks like a love story and an Alex Cross book. So the choice becomes: 'Do I want to read a page-turning love story?'"

The success of those three books led Patterson to increase his annual production by working with collaborators. He conducts the enterprise from the Florida home where he lives with his wife and 15-year-old son. The first stage is to write a 60-70 page outline for every book. "Then I'm not like a publisher who asks to see a finished work in two years. I get material from the writers every two weeks. If it's going well I say keep at it. Or I say 'stop' and let's look at those last 40 pages again if the train has gone off the track."

Patterson wasn't the first writer to openly collaborate, but he has been by far the most commercially successful. "There was a certain amount of fear from publishers. And some journalists couldn't conceive of how this guy could be involved in so many projects and therefore thought it was bullshit. But everyone who comes to my office eventually says: 'Oh. I get it'. Because around the place they will see 30-35 manuscripts in different stages of development and they have to come to realise that I am a maniac."

Patterson was born in 1947 in Newburgh, a town that was then "the all-American city, and is now the murder capital of New York state". He has said that money was not plentiful when growing up, but a greater poverty came from the emotional detachment of his father. "He never had a father around himself and while you did feel there was a bond, it wasn't expressed much. We weren't beaten. Food arrived on the table. But eventually you see that parts of it were not optimal and you try to deal with that."

As a high school valedictorian in one of the best Catholic schools in the area Patterson applied to both Harvard and Yale. "But I never even heard from them. Then I was told I had been accepted at Manhattan College, which was a Christian Brothers college I had not applied for. It turned out the brothers had never actually sent off my applications. Actually Manhattan College was fine and was where Rudy Giuliani went. But in those days if you were Catholic you went to a Catholic college."

Although a star pupil at school, he only read enough "to get out of Newburgh". It was not until his family moved to near Boston, just before he started college, and he took a part-time job at a mental hospital that he started to "read my brains out. And not commercial fiction. Stuff that really stretched me: The Tin Drum; One Hundred Years of Solitude. Working nights meant I was paid overtime and I'd go into Cambridge and buy maybe 10 books a week. The hospital was used by a lot of wealthy families, which was also a new socio-economic thing for me. And it had an artistic tradition: Robert Lowell was there for a while; Ray Charles used to check in; James Taylor; Sylvia Plath had been there before my time. There was a tradition of wonderful craziness."

He left Manhattan College with an English degree and enrolled on an MA programme at Vanderbilt University. But after receiving a "lucky" high number in the Vietnam draft lottery, in 1971 he took a job in advertising at J Walter Thompson. "I never particularly liked advertising and it hadn't been anything I'd had in mind." But he says the job was right for him when his long-term girlfriend developed a brain tumour and subsequently died. "I wanted no time by myself so I threw myself into work and went from creative director to running the company in two and a half years." Patterson was instrumental in award-winning campaigns for companies such as Kodak, Burger King and Toys R Us. But throughout this time he also wrote. It was while working at the mental hospital that he had first started "scribbling and found that I loved it. It seemed I was never going to produce a Ulysses or One Hundred Years of Solitude – although maybe I sell myself a little short in terms of magic realism, which I think I maybe could've done in an interesting way. But somewhere along the way I read Day of the Jackal and The Exorcist. I hadn't read much commercial fiction, but I liked these and thought I maybe could do books that people turn the pages of."

So he wrote The Thomas Berryman Number, a thriller about a political murder in the US deep south, which was soon turned down by 31 publishers. "But the rejections were genuinely kind and encouraging, and it wasn't long before one said yes." His debut was published in 1976 and the following year Patterson took a call in his office from the organisers of the Edgar awards for crime fiction.

"They wanted to know if I could come to their prize ceremony. I told them the date was difficult and eventually they had to break protocol and say: 'You have to come, you've won!' So I went. Although I was still half thinking they had lied just to get me there and sweated it until they said my name. And when I had my little moment to say something I said 'I guess I'm a writer now'."

In fact he continued to work in advertising, at increasingly senior levels, until 1996. His early productivity as a novelist was unremarkable and over the next 15 years he published five novels. Everything changed with the publication of his first Alex Cross story, Along Came a Spider, in 1992. Cross was a compelling character, but the book became Patterson's breakthrough because of his insistence, against all received opinion in publishing, that it should be advertised on TV.

"It didn't take a lot of study for me to look at the ads and say that some things could be done better. I thought television advertising could work and as we didn't have enough money to do it across the US, it was obvious to pick three or four significant cities. We could afford Washington, New York and Chicago. The ads went on, the book jumped onto the bestseller list, and then the bestseller list becomes your advertising."

His early work was reviewed in the normal way with much praise for his debut including nods to Chandler, and a more mixed response to the follow-ups. But as his popularity, and especially his productivity, has increased so his books are now rarely reviewed in mainstream print – although reader reviews remain plentiful. Not that this has restricted criticism: Stephen King once described him as "a terrible writer" – a fact that didn't stop Patterson including King's Different Seasons in his Publishers Weekly ad of 38 American books that would be missed – to which one of Patterson's stock lines in response is to point out that while "thousands of people hate my stuff, millions of people like it".

He acknowledges that The Thomas Berryman Number had better sentences than most of his work since, "but it didn't have a better story. Everyone has a handful of anecdotes they know people will like when they tell them. But if you wrote them out you'd see that you don't tell them in good sentences. And I became much more interested in telling those colloquial stories than I was in style."

His prose is doggedly functional with short sentences and chapters relentlessly working to propel the plot. Here's the opening of the most recent Alex Cross novel:

"It's not every day that I get a naked girl answering the door I knock on. Don't get me wrong – with twenty years of law enforcement under my belt, it's happened. Just not that often.

"Are you the waiters?" this girl asked. There was a bright but empty look in her eyes that said ecstasy to me, and I could smell weed from inside. The music was thumping, too, the kind of relentless techno that would make me want to slit my wrists if I had to listen to it for long.

"No, we're not the waiters," I told her, showing my badge. "Metro police. And you need to put something on, right now."

She wasn't even fazed. "There were supposed to be waiters," she said to no one in particular."

His discussion with collaborators is mostly at the level of "the nugget that drives every sentence and every word in a chapter, say, in which we are going to bond with two characters. Everything in it – how they meet, where they meet, how they talk, their responses to each other – is all going to make you want to read more about these two people."

And while he is aware that his work has been described as mechanical – "and maybe I am sometimes" – it is something he has come to instinctively. "I didn't study it. A lot of it is emotional with me. You have to care. So many thrillers don't work because you don't care about the characters or the situation. I saw the latest Die Hard movie and I just didn't care. In the first two, the Bruce Willis character was engaging, unusual and funny. The villains were also interesting. But when someone condescends to the genre you can smell it straight away."

He is working to a two-year schedule of 10 books a year. "It's funny that publishers were once against me writing more than one book a year. The situation has changed a lot since then. If I now said I was writing only one book this year, not 10, they would have a heart attack. They are plugged into the money."

At one stage Patterson's books generated 30% of his publisher's revenues. "That brings responsibility for me as well as them. I want them to make money. I don't send my agent in there to beat them up for every nickel he can get. But I want them motivated to do what they do well, and if they're not making money they won't be motivated."

So what part does the money play in motivating him? He had little as a child and the vast sums that now roll in have not slowed his work rate or productivity and can't all be spent on buying ad space to defend books. "My life revolves around my writing, my wife and my son. And I'm not just shovelling shit about that. That's the stuff that works for me. Yes, I do have a really big house in Florida, which is a little bit of an embarrassment." (It's a beachfront estate, next to one previously owned by John Lennon and Yoko Ono, that the Pattersons bought for $17.4m; they spent another $14m on renovations.) "It is too big and ridiculous and I don't even go to the bottom floor, but what we get back in terms of the view is glorious and I much prefer living in my money than having it in the bank."

He says the most satisfaction he received from money was when he achieved a similar status to two friends who are recently retired school teachers in Georgia. "They live in a nice town. They ride their bikes to the ocean. They have some savings and pensions and they are not worrying about money. The lack of it is such a source of unbelievable stress. Beyond that I'm not very materialistic and to some extent I've had to learn how to spend it. Now if there's something I really want I do tend to get it, so while I sometimes try to think that it doesn't really matter, I also realise I might have become a difficult person to buy Christmas presents for."

%2B(1).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment