|

| Juan Marsé |

JUAN MARSÉ CONVICTIONS AGAINST CONVENTIONS

In 2016 we celebrated fifty years since the publication of ‘Last evenings with Theresa’, one of the best Spanish novels of the 20th century; now its author will celebrate the occasion with a new literary release

Sergi Dòria

25 October 2017

In 1987, Juan Marsé defined in the third person in his last portrait of Ladies and Gentlemen: “He is not delighted to meet himself, he would have preferred to avoid himself… The guy is short, shabby, quiet, taciturn and a teaser. He does not consider himself an intellectual and cannot stand to be treated as one. He loves bars and local paper stores, the well-lit frames of street kiosks selling cartoons and cheap adventure novels. Flags fill him with deep horror. Eats salads and handwrites.” Thirty years ago, in 1957, I was already pointing towards writing, in a letter to Paulina Crusat, his literary “fairy grandmother”: “Don’t think I considered myself as ‘the chosen one’ —I would believe it when I was 18—, because if I had to define myself a little, I would say I am quite lazy, I have little drive for some things that deserve care and affection, and possess little external affection towards the others (I would love to be a mother-kissing son, but I am not, don’t ask me why), and I’m so sorry about that…”

More anniversaries. In 2016 we celebrated half a century since Last evenings with Theresa was published. The author recalls the journalist Manuel Del Arco, when he told him he had been given the Biblioteca Breve Award and the press was waiting for him in Museu Marés. Marés… Marsé. The author and his characters: Manolo, aka Pijoaparte, trying to change his barrack in Carmel for a middle-class tower in Sarrià or Cadaqués. The Murcia-born, this bronzed epigon and suburbia Stendhalian Julien Sorel; or the blonde Teresa, “a red handkerchief peering through the pocket of her white raincoat and a shaky musical disposition on her legs”. When Seix Barral re-edited Last evenings with Teresa, Arturo Pérez-Reverte pointed out to its eternal nature: “It remains as fresh as when it was written. Not even the idiots who at the time reluctantly welcomed the author’s novel, the resentful or parasites who live on writing how they would write —if they even could— books that others write, not even them dare questioning that Manolo Reyes, aka Pijoaparte, is one of the best described characters of Spanish literature of the second half of the 20th century.”

As revealed by Josep Maria Cuenca in While happiness arrives, Marsé’s biography starts like a novel. Son of Domingo Faneca and Rosa Roca, the boy who had to be called Joan Faneca Roca ended up being Juan Marsé Carbó. According to Berta Carbó, his adoptive mother had lost her own son: the fortuitous meeting in a taxi with the biological father of that orphaned boy ended up in an adoption. The truth is that Domingo Faneca and Pep Marsé, his adoptive father, had already met in the separatist party Catalan State, a dangerous friendship in post civil war Barcelona. The “story of the taxi”, points Cuenca, became an imaginative story of Berta’s: “We can now say that Juan Marsé came to the world, not with “bread in his arm”, as the proverb says, but with a novel under his arm: that “written” by his mother for him.

Not until much later did Marsé become acquainted with his own origins, in detail: “I was never interested in delving into this issue, and I never did that to avoid annoying my adoptive parents… When Cuenca began research on my family background, I let him do that. He discovered many interesting and surprising things about my genealogical tree, like descendents from Ponce de León, conquerors…” My gratitude towards my adoptive parents is clearly revealed in his acknowledgement lines in One Day I will be back: “To Pep Marsé, my father, who taught me how to combine awareness with escalivada.” But with the passage of time, memory is no longer what it used to be, as the author acknowledges: “There is a kind of degradation of one’s convictions superseded by a kind of moral ambiguity in relation to characters and facts that you considered true.” For example, the figure of an absent father, repeated and idealized in his early novels reappears with a less dignified profile in Lizard tails or Handwriting of dreams.

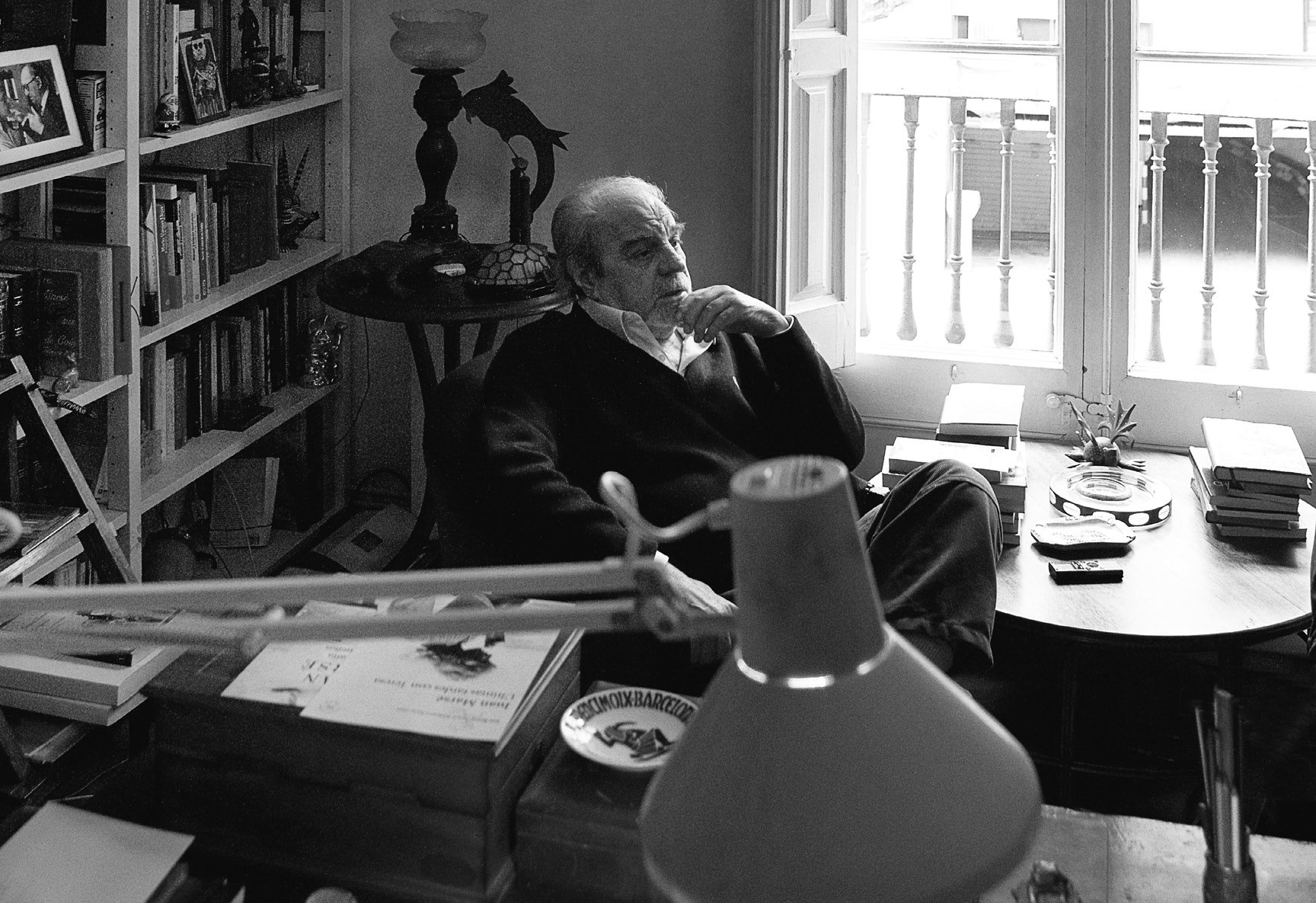

Reared in the Barcelona district of Guinardó, Marsé frames his novels in his memories, this “paradise from which nobody can expel you”. The Marsé Territory is a quarter and a skylight, cinema theatres, cartoon papers and erotism in the shades. A Barcelona that only survives on literature. The current Barcelona is “a designer city, with tourism as the main source of income”. We wonder about Bartleby’s syndrome diagnosed by Enrique Vila-Matas, we glimpse at the portrait of Gil de Biedma, presiding over his work and days. “Jaime concluded that I had nothing else to say as a poet”, explains Marsé. But this is not his case. He finishes a novel and has two more projects in mind: “Why anybody who writes has fifty thousand answers. I cannot do anything else. I disagree with a world that is not well done: fiction offers alternatives to this reality, that I don’t like.” Deeply rooted to his home country and literature, he can do without dangerous nationalistic identities. Whenever the topic arises, he looks back to Stephen Dedalus in Portrait of a Teenage Artist: “You talk to me about nationality, language, religion. Well, these are networks from which I have been trying to escape…”

He escapes indeed, just as when we try to draw from him anything about his new novel. Marsé grins and quotes Hemingway: explaining a story can end up bearing bad luck. He only offers a few glimpses, though: “The driving theme of the story line is an indictment of a person who committed a crime thirty years ago, and after an extremely aggressive therapy manages to remember how he committed the crime, but he does not know why…” Before we venture labeling it, he warns us that this is not a black novel, a gender he detests. “It is about memory traps, about forgetfulness as a therapy… The author of the indictment with the murderer is commissioned to write a script about the murder and holds a series of interviews with him… I’ve said more than enough!”, concludes.

Marsé has uttered the word script, a true battle horse for failed cinema adaptations of his novels. We look around at the many black-and-white photographies surrounding us. Literature, cinema, living other lives… We go back to the self-portrait of Ladies and Gentlemen: “Unmasking oneself, disguising oneself, camouflaging oneself, being someone else. The coyote in Las Ánimas. The hunchback in the Delicias cinema theatre. The vampire in the Roxy cinema. The monster in the Verdi cinema. Nostalgia for not having been any of them.” The cinema version of a novel, he highlights, “does not necessarily have to be tightly bound to the literary work…” We ask for examples: “Nazarín and Tristana. Buñuel adapts Galdós, but the stories are Buñuel’s. In explaining the novel, you have the novel, so read it. The error of adapting my work is that directors want to be too faithful to the original.” Better versions? “Coppola and Conrad in Apocalypse Now, Welles and Shakespeare in Chimes at Midnight, Burgess and Kubrick in Clockwise Orange…”

Marsé gives identity to his writing. Forever incorruptible. The youngster wearing a t-shirt at the jewellery workshop obsessed with Carmen Broto’s murder and the stories it would inspire years later, If they tell you I fell. Marsé, already a writer, with his first novel, Locked up with only one toy, in his hands. The tiny room of Carrer Martí: typewriter, a reading lamp, a photograph of Edith Piaf pinned up on the wall. Marsé octogenarian who dreams like a child in Happy News on Paper Planes. On the shelves, sensuous Betty Boop, Stevenson, Hollywood stars who bewitched Shanghai and his motto: “Tidiness at work is the writer’s only moral condition.”

No comments:

Post a Comment