Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom: The book that declared pop music dead

Nik Cohn thought John Lennon ‘self-pitying’, Led Zeppelin ‘embarrassing’ and rated Del Shannon’s ‘Runaway’ above Van Morrison’s entire career. Bob Stanley revisits his 1969 book

Bob Stanley

Saturday 16 February 2016

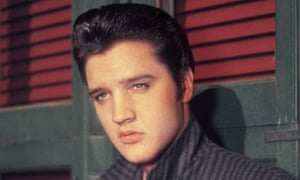

‘Great ducktail plume and lopsided grin’ … Cohn’s Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom is full of praise for Elvis. Photograph: Corbis

‘Great ducktail plume and lopsided grin’ … Cohn’s Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom is full of praise for Elvis. Photograph: Corbis

In the spring of 1968, the former Queen magazine pop columnist Nik Cohn rented a cottage in Connemara on the west coast of Ireland. All of 22, he had fallen out of love with pop music, and he hid himself away for two months to write a cross between a memoir and a farewell letter. For Cohn, it felt like the end of an era of pop that was “intelligent and simple both”, that carried its implications lightly, that was “fast, funny, sexy, obsessive, a bit epic”. He sniffed pretension in the air as pop turned to rock, and he wanted to get it all down on paper before he completely lost interest. The confidently titled Pop from the Beginning moved from Bill Haley’s Rock Around the Clock in 1955 to the ebbing tide of psychedelia and the return to roots (Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, the Beatles’ “Lady Madonna”) of early 1968. Published in 1969, just as the Beatles disintegrated, Pop from the Beginning was the first definitive text on pop music. Cohn wrote in fast, short sentences; the book read like a series of 7in singles, with no room for deviation, no long solos, no flab at all.

By the time it was reprinted as a paperback a year later, it had a new title – Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom – and a telltale subtitle: “the Golden Age of Rock”. Cohn had predicted the sea change; he had fallen out of love with pop just as the Beatles-led consensus years came to end: pop was split, hard left and right, between Radio 1 factory‑farmed pop (“Sugar, Sugar”) and self-conscious, album-based heavy rock (Led Zeppelin, Jethro Tull, Black Sabbath). For Cohn, a teddy boy at heart, neither came close to the glamour and speed fix of the rapidly receding “golden age” he wrote about with such dash: Elvis’s “great ducktail plume and lopsided grin”, Phil Spector’s “beautiful noise”, and James Brown, “the outlaw, the Stagger Lee of his time”.

Among the the reasons Cohn’s book has remained such a thrilling, inspirational read are its total confidence and absolute sense of finality. By 1969, Cohn considered John Lennon “self-pitying”, thought the Who were “going through the same old stunts”, and dismissed Pink Floyd as “very solemn, most artistic, boring almost beyond belief”. The new order spurned flash, and dressed down in T-shirts and denims; Cohn, disgusted, reacted in 1971 with a book on fashion called Today There Are No Gentlemen. He has never shown any inclination to write an updated edition of Awopbopaloobop.

Nik Cohn grew up in postwar Derry. His father was a renowned historian, Norman Cohn, which may have put young Nik off anything approaching rigour in his writing. At 13, he spent a week in London, where he found a paperback of Alan Lomax’s Mister Jelly Roll: The Fortunes of Jelly Roll Morton, New Orleans Creole and Inventor of Jazz; the cover promised to explain how “he put the heat into hot music”. Jazz historians have dismissed large chunks of Morton’s life story as wishful thinking, while confirming that he was also a hugely significant talent and influence, but aged 13, Nik Cohn didn’t care for dry history, wasn’t remotely bothered that Morton had vamped up his past. He was absorbed by tales of pimps and voodoo queens, and pictured Mister Jelly Roll as the dust jacket described him, “wearing a hundred-dollar suit as sharp as a tipster’s sheet … the diamond in a front tooth gleaming like gaslight”. The book contained a map of New Orleans – Cohn memorised every street. As a Jewish kid growing up in sectarian Ulster, he felt like an outsider and sought escape in invention; Mister Jelly Rollfed right into a mythology of flash, violence and seven-day weekends that he had first discovered through Elvis Presley’s records, and became the biggest literary influence on Cohn’s career.

Awopbopaloobop transferred the underworld grit, diamond-studded teeth and overflowing dresses in Cohn’s imagination to the glamour, the ostentation, the ruthlessness and grubbiness of the pop business. He would soon base the 1970 novel Arfur: Teenage Pinball Queen in his fictionalised New Orleans, now renamed Moriarty (“the foremost city of the nation, a compound of refinement and squalor, grace and depravity”), where there were now beautifully named quarters of Cohn’s own making – Jitney, Cicero and Savoy, “the wealthy St Jude and the shanty Canrush”.

Cohn applied this fantastical approach to the real story of pop, cutting down people he thought were likely to diminish the music’s sense of fun and fast-moving disposability (Bob Dylan, the Doors, even the Beach Boys), and to praise outsiders, troublemakers, short-lived stars whose one major hit (Del Shannon’s “Runaway”, for instance) he considered to be worth as much as Van Morrison’s entire career. Trouser-tearing PJ Proby’s profile was elevated monstrously – with all of three top 10 hits to his name, Proby was given a whole chapter in Awopbopaloobop on the strength of his outsized ego and chaotic potential. This was significant and, at the time, outrageous – in 1969, it must have seemed that seriousness had won out for good, with levity confined to novelty singles and bubblegum. After all, it had only taken John Lennon six years to get from the lung-busting liberation of Twist And Shoutto a concept album about Arthur Janov’s trauma-based primal scream therapy. Cohn took sides, and it wouldn’t have been a hard choice.

Just as he had romanticised New Orleans, Cohn set to perfecting the story of pop, from the beginning. “My purpose was clear,” he wrote in 2004. He wanted “to capture the feel, the pulse” of what he called “Superpop”, with no dry discographies or chart positions. In doing this, he latterly admitted to adding baubles and colouring. Some of the stories, he wrote in Triksta(2005), were flat-out invented.

I’d lay money on one of the embellished stories being his meeting with Gene Pitney in a hotel room, where Pitney “was talking business on a long-distance telephone … like a full-blown tycoon … tie twisted, sweatmarks under his armpits. Deals – they lit him up like neon.” I love Gene Pitney, I own a dozen of his albums and a stack of 45s, but I’d still admit that his public presentation could do with a little ornamentation. Cohn was cheeky. He thought he was doing acts such as Pitney a favour by making them seem more interesting and, most of the time, he was. It was showmanship. It was Hollywood. And it was a little depressing to read in Triksta that Cohn winced at his embellishments, and considered his younger self a fraud. In a new preface for the Vintage Classics edition of Awopbopaloobop, he seems a little more at ease: “Any man, at 70, who claims he relishes being confronted by his raw self at 22 is crazy or lying or both.” The main lesson I learned from reading Awopbopaloobop when I was 22, and a budding music writer, is that pop is all about myth-building – there’s really no such thing as authenticity or fraudulence.

Cohn also pulls out plums by being at the heart of the story as it unfolded, chronicling forgotten truths. The Beatles are now regularly credited with making pop acceptable, elevating it from the realms of teenage delinquency, and forcing critics in the Sunday papers to consider pop stars as thinkers, not just purveyors of teenage noise. Cohn doesn’t doubt the group took pop from the back streets and into the art gallery (something he strongly disapproves of), but spots an earlier turning point in Adam Faith’s 1960 appearance on the BBC TV show Face to Face. An interview programme, hosted by John Freeman, Face to Face smelled strongly of importance – guests included Augustus John, Carl Jung and Tony Hancock. Acton boy Faith had quickly become one of the biggest British pop stars of the post rock’n’roll, pre-Beatles era by dint of a hiccoughing, Buddy Holly-like vocal style, so was not expected to do anything other than embarrass himself in front of Freeman. So when he spoke neatly and smoothly on national television about his admiration for Sibelius and The Catcher in the Rye it was a minor sensation. “Pop began to go up in the world,” says Cohn. “Slowly and humbly, admittedly, but upwards just the same.”

Praising Adam Faith was never going to win you kudos from rock classicists, but Cohn wasn’t afraid of appearing uncool, or even plain wrong. Pseuds and bores, no matter how feted, were his real enemy, and he guessed the 70s would be a pretentious decade. At the conclusion of Awopbopaloobop, he predicted “formal works for pop choirs, pop orchestras; pop concerts held in halls … sounds and visuals combined … on something like a gramophone and TV set knocked into one”. Briskly, he had predicted progressive rock and MTV. Still he didn’t care; his love affair with pop was over.

After Awopbopaloobop, he spent the 70s writing novels – the super-bleak King Death (1975), which he now considers a failure – and short pieces including the clubland story “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night”, which morphed into Saturday Night Fever. But mostly he left music alone.

Even if his thoughts had been entirely negative, I’d have loved to read Cohn on Marc Bolan, Joe Strummer, Prince, even Boyzone. It’s not hard to see why he can’t be bothered now, when you look at Britain’s current crop of top-selling acts: the milky Ed Sheeran, the glum foghorn Sam Smith, and Ellie Goulding, whose major characteristic seems to be that she loves going to the gym – they simply don’t cut it. You’d never call them superstars. It isn’t just that they don’t match up to the “golden age of rock” – even the vulgar neediness of Robbie Williams or Geri Halliwell in the recent past was something to latch on to, to love or to hate. Pop music needs writers like Nik Cohn to kick up trouble, to give albums anything other than four-star reviews, and that way maybe the musicians will also rise to the challenge.

•Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom is reissued by Vintage Classics.

No comments:

Post a Comment