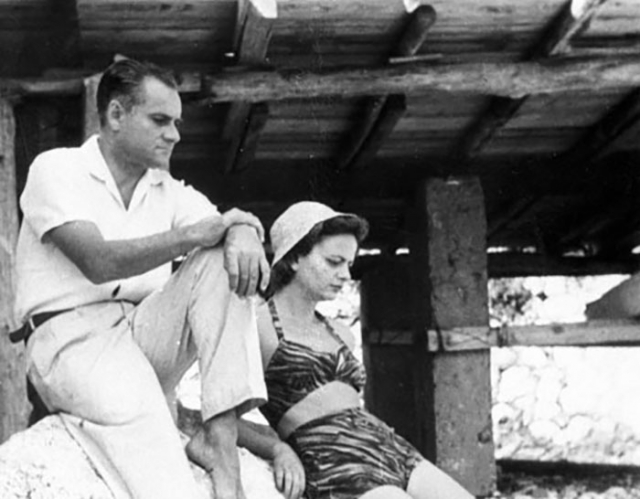

Alberto Moravia and Elsa Morante in Capri, ca. 1940s

Via dell’Oca lies just off the Piazza del Popolo. A curiously shaped street, it opens out midway to form a largo, tapering at either end, in its brief, cobbled passage from the Lungotevere to a side of Santa Maria dei Miracoli. Its name, Street of the Goose, derives, like those of many streets in Rome, from the signboard of an eating house long forgotten.

Via dell’Oca lies just off the Piazza del Popolo. A curiously shaped street, it opens out midway to form a largo, tapering at either end, in its brief, cobbled passage from the Lungotevere to a side of Santa Maria dei Miracoli. Its name, Street of the Goose, derives, like those of many streets in Rome, from the signboard of an eating house long forgotten.

On one side, extending unbroken from the Tiberside to Via Ripetta, sprawl the houses of working-class people: a line of narrow doorways with dark, dank little stairs, cramped windows, a string of tiny shops; the smells of candied fruit, repair shops, wines of the Castelli, engine exhaust; the cry of street urchins, the test-roar of a Guzzi, a caterwaul from a court.

On the opposite side the buildings are taller, vaguely out of place, informed with the serene imperiousness of unchipped cornices and balconies overspilling with potted vines, tended creepers: homes of the well-to-do. It is here, on this side, that Alberto Moravia lives, in the only modern structure in the neighborhood, the building jutting like a jade and ivory dike into the surrounding red-gold.

The door is opened by the maid, a dark girl wearing the conventional black dress and white apron. Moravia is behind her in the entry, checking the arrival of a case of wine. He turns. The interviewer may go into the parlor. He’ll be in directly.

Moravia’s living room, at first sight, is disappointing. It has the elegant, formal anonymity of a Parioli apartment rented by a film actor, but smaller; or that of a reception room at the Swiss Legation, without the travel folders—or reading matter of any sort. There is very little furniture, and this is eighteenth century. Four paintings adorn the walls: two Guttusos, a Martinelli, and, over a wide blue sofa, a Toti Scialoja. At either end of the sofa, an armchair; bracketed between the chairs and sofa, a long low Venetian coffee table inlaid with antique designs of the constellations and signs of the zodiac. The powder blue and old rose of the table are repeated in the colors of the Persian rug beneath. A record cabinet stands against the opposite wall; it contains Bach, Scarlatti, Beethoven’s Ninth and some early quartets, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Monteverdi’s Orfeo. The impersonality of the room seems almost calculated. Only the view from the windows recalls the approaching spring; flowers blossom on roof-terraces, the city is warm, red in the westering sun. Suddenly Moravia enters. He is tall, elegant, severe; the geometry of his face, its reflections, are cold, almost metallic; his voice is low, also metallic—one thinks, in each case, of gunmetal. One detects a trace of unease, shyness perhaps, in his manner, but he is at home in his parlor; he settles comfortably on the sofa and crosses his legs.

INTERVIEWER

May we start at the beginning?

ALBERTO MORAVIA

At the beginning?

INTERVIEWER

You were born . . .

MORAVIA

Oh. I was born here. I was born in Rome on the twenty-eighth of November, 1907.

INTERVIEWER

And your education?

MORAVIA

My education, my formal education that is, is practically nil. I have a grammar-school diploma, no more. Just nine years of schooling. I had to drop out because of tuberculosis of the bone. I spent, altogether, five years in bed with it, between the ages of nine and seventeen—till 1924.

INTERVIEWER

Then “Inverno di malato” must refer to those years. One understands how—

MORAVIA

You aren’t suggesting that I’m Girolamo, are you?

INTERVIEWER

Well, yes . . . .

MORAVIA

I’m not. Let me say—

INTERVIEWER

It’s the same disease.

MORAVIA

Let me say here and now that I do not appear in any of my works.

INTERVIEWER

Maybe we can return to this a little later.

MORAVIA

Yes. But I want it quite clearly understood: my works are not autobiographical in the usual meaning of the word. Perhaps I can put it this way: whatever is autobiographical is so in only a very indirect manner, in a very general way. I am related to Girolamo, but I am not Girolamo. I do not take, and have never taken, either action or characters directly from life. Events may suggest events to be used in a work later; similarly, persons may suggest future characters; but suggest is the word to remember. One writes about what one knows. For instance, I can’t say I know America, though I’ve visited there. I couldn’t write about it. Yes, one uses what one knows, but autobiography means something else. I should never be able to write a real autobiography; I always end by falsifying and fictionalizing—I’m a liar, in fact. That means I’m a novelist, after all. I write about what I know.

INTERVIEWER

Fine. In any case, your first work was Gli indifferenti.

MORAVIA

Yes.

INTERVIEWER

Will you tell us something about it?

MORAVIA

What do you want to know? I started it in October 1925. I wrote a good deal of it in bed—at Cortona, at Morra’s,* incidentally. It was published in ‘29.

INTERVIEWER

Was there much opposition to it? From the critics, that is? Or, even, from the reading public?

MORAVIA

Opposition? What kind of opposition?

INTERVIEWER

I mean, coming after D’Annunzio, at the height of Fragmentism and prosa d’arte. . .

MORAVIA

Oh . . . No, there was no opposition to it at all. It was a great success. In fact, it was one of the greatest successes in all modern Italian literature. The greatest, actually; and I can say this with all modesty. There had never been anything like it. Certainly no book in the last fifty years has been greeted with such unanimous enthusiasm and excitement.

INTERVIEWER

And you were quite young at the time.

MORAVIA

Twenty-one. There were articles in the papers, some of them running to five full columns. It was without precedent, the book’s success. I may add that nothing approaching it has happened to me since—or, for that matter, to anyone else.

INTERVIEWER

Gli indifferenti has been interpreted as a rather sharp, even bitter, efficient criticism of the Roman bourgeoisie, and of bourgeois values in general. Was it written in reaction against the society you saw about you?

MORAVIA

No. Not consciously, at least. It was not a reaction against anything. It was a novel.

INTERVIEWER

Those critics who have cast you along with Svevo are wrong, then, you would say?

MORAVIA

Quite. Yes, quite. To tell the truth, Svevo is a writer I don’t know at all well. I read him, and then only Senilità [As a Man Grows Older], and what’s the other one?—La Coscienza di Zeno [Confessions of Zeno]—after I had written Gli indifferenti. There’s no question of influence, certainly. Furthermore, Svevo was a conscious critic of the bourgeoisie; my own criticism, whatever there is, is unintentional, occurring entirely by chance. In my view, the function of a writer is not to criticize anyway; only to create living characters. Just that.

INTERVIEWER

You write, then—?

MORAVIA

I write simply to amuse myself; I write to entertain others and—and, well, to express myself. One has one’s own way of expressing oneself, and writing happens to be mine.

INTERVIEWER

By that, you do not consider yourself a moralist, do you?

MORAVIA

No, I most emphatically do not. Truth and beauty are educatory in themselves. The very fact of representing the left wing, or a “wing” of any sort, implies a partisan position and nonobjectivity. For that reason, one is impotent to criticize in a valid sense. Social criticism must necessarily, and always, be an extremely superficial thing. But don’t misunderstand me. Writers, like all artists, are concerned with representing reality, to create a more absolute and complete reality than reality itself. They must, if they are to accomplish this, assume a moral position, a clearly conceived political, social, and philosophical attitude; in consequence, their beliefs are, of course, going to find their way into their work. What artists believe, however, is of secondary importance, ancillary to the work itself. A writer survives in spite ofhis beliefs. Lawrence will be read whatever one thinks of his notions on sex. Dante is read in the Soviet Union.

A work of art, on the other hand, has a representative and expressive function. In this representation the author’s ideas, his judgments, the author himself, are engaged with reality. Criticism, thus, is no more than a part, an aspect—a minor aspect—of the whole. I suppose, putting it this way, I am, after all, a moralist to some degree. We all are. You know, sometimes you wake up in the morning in revolt against everything. Nothing seems right. And for that day or so, at least until you get over it, you’re a moralist. Put it this way: every man is a moralist in his own fashion, but he is many other things besides.

INTERVIEWER

May we return to Gli indifferenti for just a moment? Did you feel when you were working on it that you faced particular problems of technique?

MORAVIA

There was one big one in my attempt—borrowing a drama technique to begin and end the story within a brief, clearly delimited period, omitting nothing. All the action, in fact, takes place within two days. The characters dine, sleep, entertain themselves, betray one another; and that, succinctly, is all. And everything happens, as it were, “onstage.”

INTERVIEWER

Have you written for the stage?

MORAVIA

A little. There’s a stage adaptation of Gli indifferenti which I made with Luigi Squarzina, and I’ve written one play myself, La Mascherata [The Fancy Dress Party].

INTERVIEWER

Based on the book?

MORAVIA

Not exactly. The idea’s the same; much of the action has been changed, however. It’s being put on in Milan by the Piccolo Teatro.

INTERVIEWER

Do you intend to continue writing plays?

MORAVIA

Yes. Oh, yes, I hope to go on. My interest in the theater dates back a good many years. Even as a youngster I read, and I continue to read and enjoy, plays—for the most part, the masters: Shakespeare, other of the Elizabethans, Molière, Goldoni, the Spanish theater, Lope de Vega, Calderón. I’m drawn most, in my reading, to tragedy, which, in my opinion, is the greatest of all forms of artistic expression, the theater itself being the most complete of literary forms. Unfortunately, contemporary drama is nonexistent.

INTERVIEWER

How’s that? You mean, perhaps, in Italy.

MORAVIA

No. Simply that there is no modern drama. Not that it’s not being staged, but that none has been written.

INTERVIEWER

But O’Neill, Shaw, Pirandello . . .

MORAVIA

No, none of them. Neither O’Neill, Shaw, Pirandello, nor anyone else has created drama—tragedy—in the deepest meaning of the word. The basis of drama is language, poetic language. Even Ibsen, the greatest of modern dramatists, resorted to everyday language and, in consequence, by my definition failed to create true drama.

INTERVIEWER

Christopher Fry writes poetic dramas. You may have seen The Lady’s Not for Burning at the Eliseo.

MORAVIA

No.

INTERVIEWER

You might approve of him.

MORAVIA

I might. I’d have to see first.

INTERVIEWER

And your film work?

MORAVIA

Script writing, you mean? I haven’t actually done much, and what little I’ve done I haven’t particularly enjoyed.

INTERVIEWER

Yet it is another art form.

MORAVIA

Of course it is. Certainly. Wherever there is craftsmanship there is art. But the question is this: up to what point will the motion picture permit full expression? The camera is a less complete instrument of expression than the pen, even in the hands of an Eisenstein. It will never be able to express all, say, that Proust was capable of. Never. For all that, it is a spectacular medium, overflowing with life, so that the work is not entirely a grind. It’s the only really alive art in Italy today, owing to its great financial backing. But to work for motion pictures is exhausting. And a writer is never able to be more than an idea-man or a scenarist—an underling, in effect. It offers him little satisfaction apart from the pay. His name doesn’t even appear on the posters. For a writer it’s a bitter job. What’s more, the films are an impure art, at the mercy of a welter of mechanisms—gimmicks, I think you say in English—ficelles. There is little spontaneity. This is only natural, of course, when you consider the hundreds of mechanical devices that are used in making a film, the army of technicians. The whole process is a cut-and-dried affair. One’s inspiration grows stale working in motion pictures; and worse, one’s mind grows accustomed to forever looking for gimmicks and by so doing is eventually ruined, shot. I don’t like film work in the least. You understand what I mean: its compensations are not, in a real sense, worthwhile; hardly worth the money unless you need it.

INTERVIEWER

Could you tell us a little about La Romana [The Woman of Rome]?

MORAVIA

La Romana started out as a short story for the third page. I began it on November 1, 1945. I had intended it to run to no more than three or four typescript pages, treating the relations between a woman and her daughter. But I simply went on writing. Four months later, by March 1, the first draft was finished.

INTERVIEWER

It was not a case of the tail running away with the dog?

MORAVIA

It was a case, simply, of my thinking initially that I had a short story and finding four months later that it was a novel instead.

INTERVIEWER

Have there been times when characters have got out of hand?

MORAVIA

Not in anything I’ve published. Whenever characters get out of control, it’s a sign that the work has not arisen from genuine inspiration. One doesn’t go on then.

INTERVIEWER

Did you work from notes on La Romana? Rumor has it—

MORAVIA

Never. I never work from notes. I had met a woman of Rome—ten years before. Her life had nothing to do with the novel, but I remembered her, she seemed to set off a spark. No, I have never taken notes or ever even possessed a notebook. My work, in fact, is not prepared beforehand in any way. I might add, too, that when I’m not working I don’t think of my work at all. When I sit down to write—that’s between nine and twelve every morning, and I have never, incidentally, written a line in the afternoon or at night—when I sit at my table to write, I never know what it’s going to be till I’m under way. I trust in inspiration, which sometimes comes and sometimes doesn’t. But I don’t sit back waiting for it. I work every day.

INTERVIEWER

I suppose you were helped some by your wife. The psychology . . .

MORAVIA

Not at all. For the psychology of my characters, and for every other aspect of my work, I draw solely upon my experience; but understand, never in a documentary, a textbook, sense. No, I met a Roman woman called Adriana. Ten years afterward I wrote the novel for which she provided the first impulse. She has probably never read the book. I only saw her that once; I imagined everything, I invented everything.

INTERVIEWER

A fantasia on a real theme?

MORAVIA

Don’t confuse imagination and fantasy; they are two distinct actions of the mind. Benedetto Croce makes a great distinction between them in some of his best pages. All artists must have imagination, some have fantasy. Science fiction, or—well, Ariosto . . . that’s fantasy. For imagination, take Madame Bovary. Flaubert has great imagination, but absolutely no fantasy.

INTERVIEWER

It’s interesting that your most sympathetic characters are invariably women: La Romana, La Provinciale, La Messicana. . . .

MORAVIA

But that’s not a fact. Some of my most sympathetic characters have been men, or boys like Michele in Gli indifferenti, or Agostino in Agostino, or Luca in La Disubbidienza. I’d say, in fact, that most of my protagonists are sympathetic.

INTERVIEWER

Marcello Clerici too? [The Conformist].

MORAVIA

Yes, Clerici too. Didn’t you think him so?

INTERVIEWER

Anything but—more like Pratolini’s Eroe del nostro tempo. You don’t mean that you actually felt some affection for him?

MORAVIA

Affection, no. More, pity. He was a pitiable character—pitiable because a victim of circumstance, led astray by the times, a traviato. But certainly he was not negative. And here we’re closer to the point. I have no negative characters. I don’t think it’s possible to write a good novel around a negative personality. For some of my characters I have felt affection, though.

INTERVIEWER

For Adriana.

MORAVIA

For Adriana, yes. Certainly for Adriana.

INTERVIEWER

Working without notes, without a plan or outline or anything, you must make quite a few revisions.

MORAVIA

Oh, yes, that I do do. Each book is worked over several times. I like to compare my method with that of painters centuries ago, proceeding, as it were, from layer to layer. The first draft is quite crude, far from being perfect, by no means finished; although even then, even at that point, it has its final structure, the form is visible. After that I rewrite it as many times—apply as many “layers”—as I feel to be necessary.

INTERVIEWER

Which is how many as a rule?

MORAVIA

Well, La Romana was written twice. Then I went over it a third time, very carefully, minutely, until I had it the way I wanted it, till I was satisfied.

INTERVIEWER

Two drafts, then, and a final, detailed correction of the second manuscript, is that it?

MORAVIA

Yes.

INTERVIEWER

And that’s usually the case, two drafts?

MORAVIA

Yes. It was three times with II conformista, too.

INTERVIEWER

Who do you consider to have influenced you? For example, when you wrote Gli indifferenti?

MORAVIA

It’s difficult to say. Perhaps, as regards narrative technique, Dostoyevsky and Joyce.

INTERVIEWER

Joyce?

MORAVIA

Well, no—let me explain. Joyce only to the extent that I learned from him the use of the time element bound with action. From Dostoyevsky I had an understanding of the intricacies of the dramatic novel. Crime and Punishmentinterested me greatly, as technique.

INTERVIEWER

And other preferences, other influences? Do you feel, for instance, that your realism stems from the French?

MORAVIA

No. No, I wouldn’t say so. If there is such a derivation, I’m not at all conscious of it. I consider my literary antecedents to be Manzoni, Dostoyevsky, Joyce. Of the French, I like, primarily, the eighteenth century, Voltaire, Diderot; then, Stendhal, Balzac, Maupassant.

INTERVIEWER

Flaubert?

MORAVIA

Not particularly.

INTERVIEWER

Zola?

MORAVIA

Not at all! . . . I’ve got a splitting headache. I’m sorry. Here, have some more. Will you take some coffee? Where was I?

INTERVIEWER

You don’t like Zola. Do you read any of the poets?

MORAVIA

I like Rimbaud and Baudelaire very much and some modern poets who are like Baudelaire.

INTERVIEWER

And in English?

MORAVIA

I like Shakespeare—everybody has to say this, but then it’s true, it’s necessary. I like Dickens, Poe. Many years ago I tried translating some poems from John Donne. I like the novelists: Butler, there’s a beautiful novel. Among the more recent, Thomas Hardy, Joseph Conrad—I think he’s a great writer—some of Stevenson, some of Woolf. Dickens is good only in Pickwick Papers; the rest is no good. (My next book will be a little like that—no plot.) I have always preferred comic books to tragic books. My great ambition is to write a funny book, but, as you know, it’s the most difficult thing of all. How many are there? How many can you name? Not many: Don Quixote, Rabelais, The Pickwick Papers, The Golden Ass, the Sonnets of Belli, Gogol’s Dead Souls, Boccaccio and The Satyricon—these are my ideal books. I would give all to have written a book like Gargantua. (He smiles.) My literary education, as you will have seen by now, has been for the most part classical—classical prose and classical drama. The realists and naturalists, to be perfectly frank, don’t interest me very much.

INTERVIEWER

They do interest, apparently, and have had a considerable influence upon the young writers who have appeared since the war. Especially the Americans seem to have been an influence: Hemingway, Steinbeck, Dos Passos . . .

MORAVIA

Yes, that’s quite so from what I know of postwar Italian writing. But the influence has been indirect: distilled through Vittorini. Vittorini has been the greatest of all influences upon the younger generation of Italian writers. The influence is American just the same, as you suggest; but Vittorini-ized American. I was once judge in a competition held by l’Unità to award prizes for fiction. Out of fifty manuscripts submitted, a good half of them were by young writers influenced by Vittorini—Vittorini and the sort of “poetic” prose you can find in Hemingway in places, and in Faulkner.

INTERVIEWER

Still, editing Nuovi argomenti you must see a great deal of new writing.

MORAVIA

How I wish I did! Italian writers are lazy. All in all, I receive very little. Take our symposium on communist art. We were promised twenty-five major contributions. And how many did we get? Just imagine—three. It’s really a task running a review in Italy. What we need, and don’t get, are literary and political essays of length, twenty to thirty pages. We get lots of little four- and five-page squibs; only that’s not what we’re looking for.

INTERVIEWER

But I meant fiction. Editing Nuovi argomenti, you must know more about modern Italian fiction than you admit.

MORAVIA

No; quite truthfully, I know only those writers everybody knows. Besides, you don’t have to read everything to know what you like. I’d rather not name any names; there would be terrible gaps and gaffes.

INTERVIEWER

How do you account for the big empty spaces in the novel tradition of Italy? Could you tell us a little about the novel in Italy?

MORAVIA

That’s a pretty large question, isn’t it? But I’ll try to answer. I think one could say that Italy has had the novel, way back. When the bourgeois was really bourgeois, in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, narrative was fully developed (remember that all that painting was narrative too) but since the Counter-Reformation, Italian society doesn’t like to look at itself in a mirror. The main bulk of narrative literature is, after all, criticism in one form or another. In Italy when they say something is beautiful that’s the last word: Italians prefer beauty to truth. The art of the novel, too, is connected with the growth and development of the European bourgeoisie. Italy hasn’t yet achieved a modern bourgeoisie. Italy is really a very old country; in some ways it looks new because it’s so old. Culturally, now, it follows the rest of Europe: does what the others do, but later. Another thing—in our literary history, there are great writers—titans—but no middle-sized ones. Petrarch wrote in the fourteenth century, then for four centuries everybody imitated him. Boccaccio completely exhausted the possibilities of the Italian short story in the fourteenth century. Our golden centuries were then, our literary language existed then, had crystallized. England and France had their golden centuries much later. Take, for example, Dante. Dante wrote a pure Italian, is still perfectly understandable. But his contemporary Chaucer wrote in a developing tongue: today he must be practically translated for the modern reader. That’s why most modern Italian writers are not very Italian, and must look abroad for their masters: because their tradition is so far back there, is really medieval. In the last ten years, they’ve looked to America for their masters.

INTERVIEWER

Will you tell us something now about your Racconti romani?

MORAVIA

There’s not much I can say about them. They describe the Roman lower classes and petite bourgeoisie in a particular period after the war.

INTERVIEWER

Is that all? I mean, there’s nothing you can add to that?

MORAVIA

What can I add? Well, no, really—really there’s quite a bit I can say. There’s always a lot I can say about my last publication. Ask me questions and I’ll try to answer whatever you ask.

INTERVIEWER

To be truthful, I’ve read only one of them. I don’t usually see the Corriere della sera, and the book itself is rather expensive. . . .

MORAVIA

Twenty-four hundred lire.

INTERVIEWER

In any case, you have not heretofore, or at least not often, dealt with the lower classes and petite bourgeoisie. These stories are a clear departure from your previous work. Perhaps you might say something about any problems in particular that you faced in writing them.

MORAVIA

Each of my books is the result, if not of pre-design, of highly involved thought. In writing the Racconti romani there were specific problems I had to cope with—problems of language. Let me begin this way: up to the Racconti romani all of my works had been written in the third person, even when, as in La Romana and since—in the novel I have just finished—told in the first person. By third person I mean simply expressing oneself in a sustained literary style, the style of the author. I’ve explained this, by the way, in a note to the Penguin edition of The Woman of Rome. In the Racconti romani, on the other hand, I adopted for the first time the language of the character, the language of the first person; but then again, not the language precisely, rather the tone of the language. There were advantages and disadvantages in taking this tack. Advantages for the reader in that he was afforded greater intimacy; he entered directly into the heart of things; he was not standing outside peeping in. The method was essentially photographic. The great disadvantage of the first person consists of the tremendous limitations imposed upon what the author can say. I could deal only with what the subject himself might deal with, speak only of what the subject might speak of. I was even further restricted by the fact that, say, a taxi driver could not speak with any real knowledge even of a washerwoman’s work, whereas in the third person I might permit myself to speak of whatever I wished. Adriana, the Woman of Rome, speaking in my third-first person, could speak of anything in Rome that I myself, also a Roman, could speak of.

The use of the first-person mode in treating the Roman lower classes implies, of course, the use of dialect. And the use of dialect imposes stringent limitations upon one’s material. You cannot say in dialect all that you may say in the language itself. Even Belli, the master of romanesco, could speak of certain things, but was prevented from speaking of others. The working classes are narrowly restricted in their choice of expression, and personally I am not particularly predisposed to dialect literature. Dialect is an inferior form of expression because it is a less cultivated form. It does have its fascinating aspects, but it remains cruder, more imperfect, than the language itself. In dialect one expresses chiefly, and quite well, primal urges and exigent necessities—eating, sleeping, drinking, making love, and so forth.

In the Racconti romani—there are sixty-one in the volume, though I’ve written more than a hundred of them now; they are my chief source of income—the spoken language is Italian, but the construction of the language is irregular, and there is here and there an occasional word in dialect to capture a particular vernacular nuance, the flavor and raciness of romanesco. It is the only book in which I’ve tried to create comic characters or stories—for a time everybody thought I had no sense of humor.

I’ve tried in these stories, as I have said, to depict the life of the sub-proletariat and the très petite bourgeoisie in a period just after the last war, with the black market and all the rest. The genre is picaresque. The picaro is a character who lives exclusively as an economic being, the Marxist archetype, in that his first concern is his belly: eating. There is no love, genuine romantic love; rather, and above all, the one compelling fact that he must eat or perish. For this reason, the picaro is also an arid being. His life is one of trickery, deception, dishonesty if you will. The life of feelings, and with it the language of sensibility, begin on a rather more elevated level.

INTERVIEWER

Themes have a way of recurring throughout your work.

MORAVIA

Of course. Naturally. In the works of every writer with any body of work to show for his effort, you will find recurrent themes. I view the novel, a single novel as well as a writer’s entire corpus, as a musical composition in which the characters are themes, from variation to variation completing an entire parabola; similarly for the themes themselves. This simile of a musical composition comes to mind, I think, because of my approach to my material; it is never calculated and pre-designed, but rather instinctive: worked out by ear, as it were.

INTERVIEWER

One last book now. We can’t discuss them all. But will you tell us something about La Mascherata? That, and how it ever got by the censors.

MORAVIA

Ah, now that you mention it, that was one time when I was concerned with writing social criticism. The only time, however. In 1936, I went to Mexico, and the Hispano-American scene suggested to me the idea for a satire. I returned and for several years toyed with the idea. Then, in 1940, I went to Capri and wrote it. What happened afterward—you asked about the censors—is an amusing story. At least it seems amusing now. It was 1940. We were in the full flood of war, Fascism, censorship, et cetera, et cetera. The manuscript, once ready, like all manuscripts, had to be submitted to the Ministry of Popular Culture for approval. This Ministry, let me explain, was overrun by grammar-school teachers who received three hundred lire, about six or seven thousand now, for each book they read. And, of course, to preserve their sinecures, whenever possible they turned in negative judgments. Well, I submitted the manuscript. But whoever read it, not wishing to take any position on the book, passed it to the Under Secretary; the Under Secretary, with similar qualms, passed it to the Secretary; the Secretary to the Minister; and the Minister, finally—to Mussolini.

INTERVIEWER

I suppose, then, you were called on the carpet?

MORAVIA

Not at all. Mussolini ordered the book to be published.

INTERVIEWER

Oh!

MORAVIA

And it was. A month later, however, I received an unsigned communication notifying me that the book was being withdrawn. And that was that. The book didn’t appear again till after the Liberation.

INTERVIEWER

Was that your only tilt with the censors?

MORAVIA

Oh, no; not by any means! I’ve been a lifelong anti-Fascist. There was a running battle between me and the Fascist authorities beginning in ‘29 and ending with the German occupation in 1943, when I had to go into hiding in the mountains, near the southern front, where I waited nine months until the Allies arrived. Time and again my books were not allowed to be mentioned in the press. Many times by order of the Ministry of Culture I lost jobs I held on newspapers, and for some years I was forced to write under the pen name of Pseudo.

Censorship is an awful thing! And a damned hardy plant once it takes root! The Ministry of Culture was the last to close up shop. I sent Agostino to them two months before the fall of Fascism, two months before the end. While all about them everything was toppling, falling to ruin, the Ministry of Popular Culture was doing business as usual. Approval looked not to be forthcoming; so one day I went up there, to Via Veneto—you know the place; they’re still there, incidentally; I know them all—to see what the trouble was. They told me that they were afraid that they wouldn’t be able to give approval to the book. My dossier was lying open on the desk, and when the secretary left the room for a moment I glanced at it. There was a letter from the Brazilian cultural attaché in it, some poet, informing the Minister that in Brazil I was considered a subversive. In Brazil of all places! But that letter, that alone, was enough to prevent the book’s publication. Another time—it was forLe Ambizioni sbagliate (The Wheel of Fortune)—when I went up, I found the manuscript scattered all over the place, in several different offices, with a number of different people reading parts of it! Censorship is monstrous, a monstrous thing! I can tell you all you want to know about it.

They started out, however, rather liberal. With time they grew worse. Besides filling up the Ministry with timid grammar-school teachers, the censors were also either bureaucrats or failed writers; and heaven help you if your book fell into the hands of one of those “writers”!

INTERVIEWER

And how is it for the writer today? You said the censors were “still there.”

MORAVIA

The writer has nothing to fear. He can publish whatever he wishes. It’s those in the cinema, and in the theater, who have it bad.

INTERVIEWER

What about the Index?

MORAVIA

The Index isn’t really censorship, at least not in Italy. The Vatican is one thing and Italy is another, two separate and distinct states. If it were to come to power in Italy, or if it were to gain the power that it has in Ireland or Spain, then it would be very serious.

INTERVIEWER

One would have thought, however, by your protest when you were placed on the Index, that you regarded it as an abridgment of your freedom as a writer.

MORAVIA

No, it wasn’t that. I was certainly upset, but mostly because I disliked the scandal.

INTERVIEWER

Anyway, it must have increased your sales. I remember it was about then that Bompiani started bringing out your collected works in deluxe editions.

MORAVIA

No, in Italy the Index doesn’t affect one’s sales one way or the other. I’ve always sold well, and there was no appreciable rise in sales after the Index affair.

INTERVIEWER

You do not see the possibility of Italy’s falling to a new totalitarian regime?

MORAVIA

There’s the possibility, but a quite remote one. If we were to come under a new totalitarianism, writers, I now believe, would have no decent recourse but to give up writing altogether.

INTERVIEWER

Incidentally, what do you think of the future of the novel?

MORAVIA

Well, the novel as we knew it in the nineteenth century was killed off by Proust and Joyce. They were the last of the nineteenth-century writers—great writers. It looks now as if we were going toward the roman à idée or toward the documentary novel—either the novel of ideas, or else the novel of life as it goes on, with no built-up characters, no psychology. It’s also apparent that a good novel can be of any kind, but the two forms that are prevalent now are the essay-novel and the documentary novel or personal experience, quelque chose qui arrive. Life has taken two ways in our time: the crowd and the intellectuals. The day of the crowd is all accident; the day of the intellectual is all philosophy. There is no bourgeoisie now, only the crowd and the intellectuals.

INTERVIEWER

What about “literature as scandal” that so concerns the French?

MORAVIA

Oh, it’s going on thirty years now that they’ve been scandalizing one another.

INTERVIEWER

And in your own work, do you see a new direction?

MORAVIA

I’ll go on writing novels and short stories.

INTERVIEWER

You do not foresee a time, then, when you will occupy your mornings otherwise.

MORAVIA

I do not foresee a time when I shall feel that I have nothing to say.

*Count Umberto Morra di Lavriano, literary critic, historian, and translator, responsible for the introduction of Virginia Woolf’s writings to Italy; now director of the Societá Italiana per l’Organizzazione Internazionale.

No comments:

Post a Comment