While the Women are Sleeping

by Javier Marías – review

by Javier Marías – review

This collection of ghostly short stories does not do justice to the novelist's brilliance

Julius Purcell

The Observe , Sunday 12 December 2010

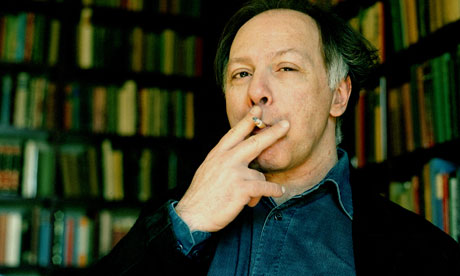

Anglophile Javier Marias at home in Madrid. Photograph: Eamonn McCabe

In a literary fiction market wary of translations, few writers have bucked the trend better than Javier Marías, who has captured a devoted English-speaking readership for his difficult but remarkable novels. When the final book of his trilogy came out earlier this year, Antony Beevor regarded it as "one of the great novels in modern European literature", and this newspaper described it as "an extraordinary work of art".

While the Women are Sleeping

by Javier Marias

In the light of such praise, those venturing into Marías territory for the first time might be puzzled by this collection of 10 short stories, centring on the supernatural and the macabre. Although the jacket blurb promises a series of tales spanning his writing career, only one is, in fact, published after 1990: the rest are strung out across the 1980s and 1970s, and the earliest hails from 1965.

This last, "The Life and Death of Marcelino Iturriaga", was written against the backdrop of the drab Franco-era Madrid of Marías's teenage years. It is narrated from within the grave by a man whose sole distraction is being visited by his widow once a month. Marías was 14 when he wrote it, a precocious foreshadowing of the extraordinarily powerful novels of the 1990s, such as Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me and A Heart So White.

This last, "The Life and Death of Marcelino Iturriaga", was written against the backdrop of the drab Franco-era Madrid of Marías's teenage years. It is narrated from within the grave by a man whose sole distraction is being visited by his widow once a month. Marías was 14 when he wrote it, a precocious foreshadowing of the extraordinarily powerful novels of the 1990s, such as Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me and A Heart So White.

In general, though, these short stories have not aged well. A great translator as well as writer (he has rendered Sterne, Conrad and Faulkner into Spanish), Marías has always worn his anglophilia on his sleeve. The story in this collection in which a Madrid businessman is disturbed to meet his double at a dinner is so close to Edgar Allan Poe's story "William Wilson" that the narrator obligingly references it in the first paragraph. Elsewhere, "Lord Rendall's Song", supposedly an extract from a lost book, reads like the kind of framing device beloved of MR James and other spooky fabulists of the Victorian gothic.

The problem is that such period pieces, far from being dusted off and reshaped, are deferentially reproduced. Another story begins: "Mr James Lawson... had just that morning re-arranged the window display of the bookstore of which he was manager, Bertram Rota Ltd, Long Acre, Covent Garden, one of the most prestigious and discriminating second-hand bookshops in London." Perhaps readers of the original Spanish enjoyed the exotic allusiveness of this. But translated "back" into English, it sounds motheaten.

Marías is far from Victorian, though, when it comes to sex. The title story, "While the Women Are Sleeping", recounts a nocturnal conversation with a fat, vain Barcelonan who obsessively videos his much younger wife before making some unpleasant revelations about what he wants to do with her when she starts to age. "I am drawn to the weird and dirty in sex," a character in another story notes. Overlaying the English tweediness is something of the transgressive hedonism of Spain's 1980s and early 1990s: the spirit of Jamón, Jamón crossed with Robert Louis Stevenson.

Every now and then there is a glimmer of the greatness of Marías's later novels. "Isaac's Journey" is a Lovecraft-style riddle about a Cuban soldier whose heirs are doomed to die before the age of 50. His grandson is never born, not because he has escaped the curse, but because the "person who is not conceived dies the most". Elsewhere, in the most recent story, "A Kind of Nostalgia Perhaps", a Mexican woman falls in love with the ghost of the revolutionary Emiliano Zapata, with whom she communicates her desire, frustration and increasing bitterness by reading him aloud the works of Dickens.

For all his reverence for the English tale, Marías is a novelist at heart. Like powerful, majestic serpents, his long sentences, with their mix of elevated and informal language, need time and space in which to flail and writhe to their full effect. While his later, mature novels are unquestionably haunting (to use the English word he is so fascinated by), the ghosts of this collection seem rather more like empty shadows. Shadows, you might say, of his future self.

%2B(1).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment