Javier Marías

Two novels by an enigmatic Spanish author explore past and present.

By WENDY LESSER

May 6, 2001

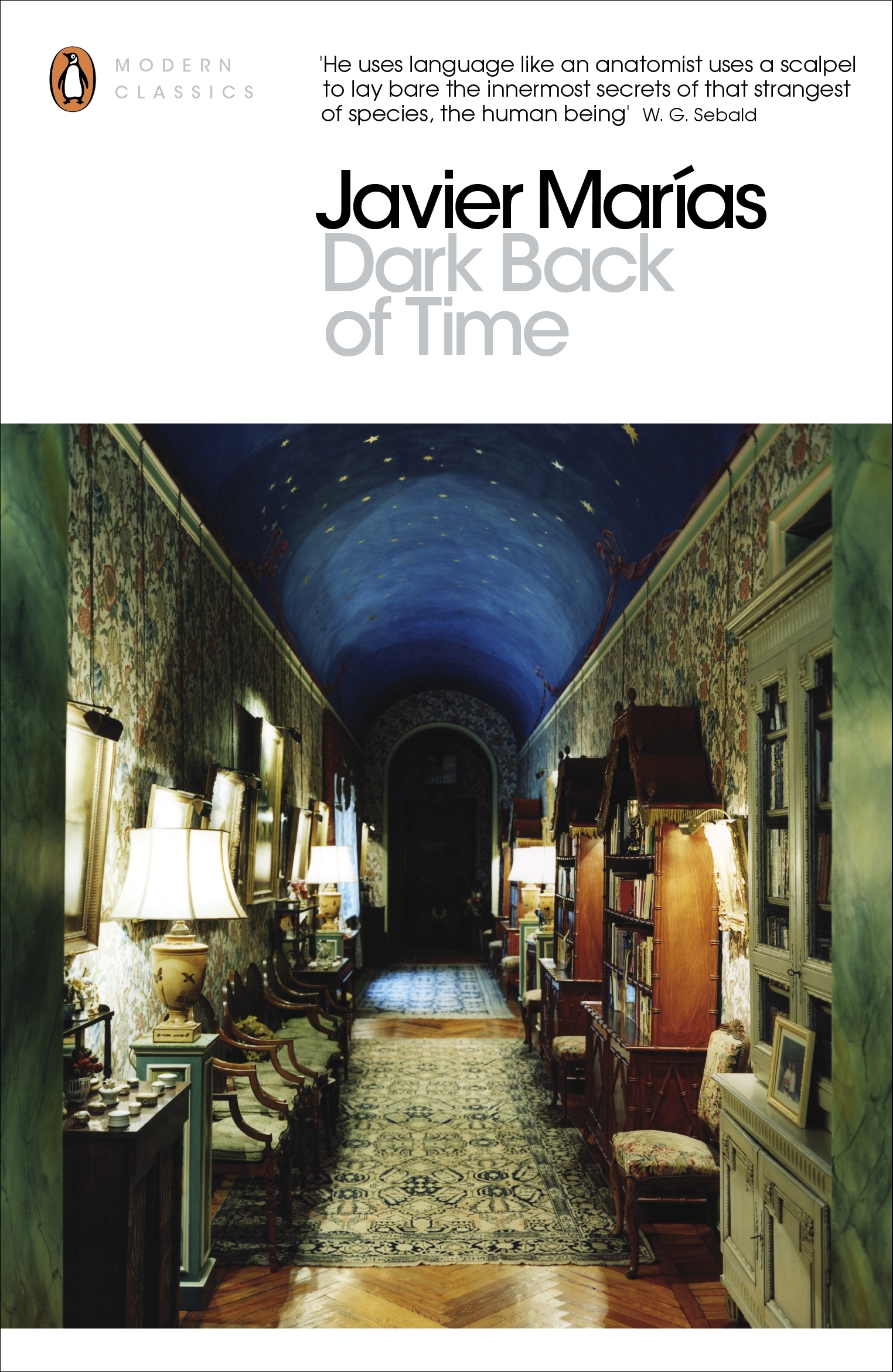

A HEART SO WHITE By Javier Marías. Translated by Margaret Jull Costa.  DARK BACK OF TIMEBy Javier Marías. Translated by Esther Allen. |

ere plot summary would give you a mistaken impression. A nameless Spaniard spends two years teaching at Oxford, has an affair with a married woman and buys a lot of rather obscure old English books. A man in Madrid is about to have an affair with a married woman when she drops dead in his arms; he flees the scene and spends the next few months surreptitiously getting to know the surviving members of her family. A simultaneous translator, recently married to another simultaneous translator, uses the growing friendship between his wife and his father to unravel the mystery behind a suicide that took place before he was born. An author reflects on the strange events -- many of them involving eccentric Englishmen, others having to do with his own private and public life -- that are connected to the publication of one of his earlier novels.

These are the story lines (though that may be precisely the wrong word, for they come to us in circular, disconnected form) of ''All Souls,'' ''Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me,'' ''A Heart So White'' and ''Dark Back of Time,'' the four novels by the Spanish writer Javier Marías that are now available in English. If you judged by the summaries alone, you might guess that Marías's fiction is ludicrously melodramatic or cruelly comic or tediously postmodern. It is none of these. On the contrary, all four novels possess an odd combination of true sadness and deeply satisfying wit that I have yet to find in any of Marías's English or American contemporaries.

Although this review will concentrate on the two novels that are most recently available, it is difficult, with Marías, to segregate any single work from the others. The experience of reading him is cumulative. When you take up a Marías novel or even a Marías short story, you are at once enclosed in a strange world that becomes increasingly and addictively familiar. Names and characters recur: the wives are often called Luisa, a slightly suspect friend will be either Custardoy or Ruibérriz de Torres, and there are frequent references to an Englishman named John Gawsworth and his position as king of Redonda. Public figures, too, put in an appearance, though Franco is not always called Franco, and Margaret Thatcher may simply be identified as a female British leader. The events take place mainly in Madrid, but London, Oxford, Havana, Venice and New York are also knowledgeably invoked. Time is an active presence, a nearly tangible entity. Ghosts flit through; sometimes (as in the title story in the collection ''When I Was Mortal'') they even act as narrators.

"I did not want to know but I have since come to know that one of the girls, when she wasn't a girl anymore and hadn't long been back from her honeymoon, went into the bathroom, stood in front of the mirror, unbuttoned her blouse, took off her bra and aimed her own father's gun at her heart, her father at the time was in the dining room with other members of the family and three guests. When they heard the shot, some five minutes after the gift had left the table, her father didn't get up at once, but stayed there for a few seconds, paralysed, his mouth still full of food, not daring to chew or swallow, far less to spit the food out on to his plate; and when he finally did get up and run to the bathroom, those who followed him noticed that when he discovered the blood-spattered body of his daughter and clutched his head in his hands, he kept passing the mouthful of meat from one cheek to the other, still not knowing what to do with it."-- from the first chapter of 'A Heart So White' |

For the most part, in fact, the narrator of a Marías novel is the story. In ''A Heart So White,'' he is an intelligently curious but somewhat timid figure, overshadowed -- in his own mind and, he fears, everyone else's -- by his powerful, seductive father, a man named Ranz who deals in valuable artworks and has a forger for a best friend. Our narrator learns that Ranz, before being married to his mother, was briefly married to her older sister, a young woman who killed herself soon after the wedding. It is this death, in other words, that gave rise to the narrator's own life. (This is exactly the kind of thought a Marías narrator is always having; you can see how easily the ghosts slip in.) To solve the mystery behind this suicide, he must use his wife as bait -- or, rather, he must depend on his wife's increasing closeness to her father-in-law to elicit the desired yet finally unwelcome information.The narrator of ''A Heart So White'' is capable of strong passion -- particularly in regard to his wife -- but we hear from him mainly about the passions of others. He is the kind of man who watches life through a window, either from a room looking down onto the street (as he does on his honeymoon in Havana) or from street level, generally at night, looking up at a lighted window (as he does during a trip to New York, when he is waiting to go back to the apartment of his friend Berta, who is having a tryst with a man she met through a video introduction service). And in this he is typical of all Javier Marías narrators: they inevitably adopt this peering pose at some point or another. It is a pose that is also a philosophical position -- a reflection on how much or how little people can really know about one another; a commentary on suspicion and guesswork and, finally, helplessness in the face of events.

But again, I have created the wrong impression if I have made the Marías narrator sound like a voyeur. He is intimately involved in the events he describes, and he is also intimately involved with us, his readers. Like Henry James's or Marcel Proust's, his sinuous, flattering, seemingly endless sentences presume -- even insist -- that we are as subtle and intelligent as the author. And their subject matter is Proustian or Jamesian as well -- Marías is interested not so much in the violent death or the adulterous love affair itself as in how we think and feel about such events when we contemplate them beforehand or consider them afterward. (That this Jamesian quality has been preserved in English is a great tribute to Marías's translators, Esther Allen and especially Margaret Jull Costa. But it may also be attributable to the fact that Marías's fiction in some way comes from English: he has done Spanish translations of Sterne, Hardy, Stevenson and Faulkner, among others.)

The Associated Press |

| Javier Marías |

Like the work of Jorge Luis Borges, of which it may superficially remind you, ''Dark Back of Time'' deals repeatedly and amusingly with the relationship between reality and the written word. But where Borges is cold, Marías is warm: his breath is in our ear, his urban reality is essentially our urban reality, and -- despite his interest in ghosts -- he is very much alive right now. He has seen the same movies we have, danced to the same music, read the same books, gone to the same kinds of restaurants and racetracks and academic meetings. He is even capable, at times, of anticipating our thoughts and memories, as if he were performing a version of a simultaneous translation on us, rendering our hidden suspicions into mutually acknowledged words.

It is a rare gift, to be offered a writer who lives in our own time but speaks with the intensity of the past, who comes with the extra richness lent by a foreign history and nonetheless knows our own culture inside out. Yet, strangely, Javier Marías -- who is famous in Spain and garlanded with prizes from the rest of Europe -- remains almost unknown in America. What are we waiting for? All the gifts we are offered in life (as Marías himself is fond of pointing out) are fleeting ones, easily lost or ignored or undervalued and only regretted when they are no longer available to us. It's high time we accepted this one.

NY TIMES

Wendy Lesser is the editor of The Threepenny Review and the author of five books. She is currently a senior fellow at Columbia University's National Arts Journalism Program.

%252B(1).jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

DRAGON

Javier Marías / The Art of Fiction

Javier Marías turns down prize

Javier Marías / Fewer Scruples

Javier Marías / A Heart So White / Quotes

Javier Marías / A Heart So White / Reviewed by Samantha Scheneed and Others

Javier Marías / Stranger than Fiction

Javier Marías / A Heart So White / JDP

Javier Marías / While the Women Are Sleeping

Javier Marías / While the Women Are Sleeping / Reviews

Javier Marías / A Heart So White and All Souls

Javier Marías / There are seven reasons not to write novels (and one to write them)

Javier Marías / A life in writing

The Infatuations by Javier Marías / Review by Robert McCrum

The Infatuations by Javier Marías / Review by Alberto Manguel

Javier Marías turns down prize

Javier Marías / Fewer Scruples

Javier Marías / A Heart So White / Quotes

Javier Marías / A Heart So White / Reviewed by Samantha Scheneed and Others

Javier Marías / Stranger than Fiction

Javier Marías / A Heart So White / JDP

Javier Marías / While the Women Are Sleeping

Javier Marías / While the Women Are Sleeping / Reviews

Javier Marías / A Heart So White and All Souls

Javier Marías / There are seven reasons not to write novels (and one to write them)

Javier Marías / A life in writing

The Infatuations by Javier Marías / Review by Robert McCrum

The Infatuations by Javier Marías / Review by Alberto Manguel

No comments:

Post a Comment