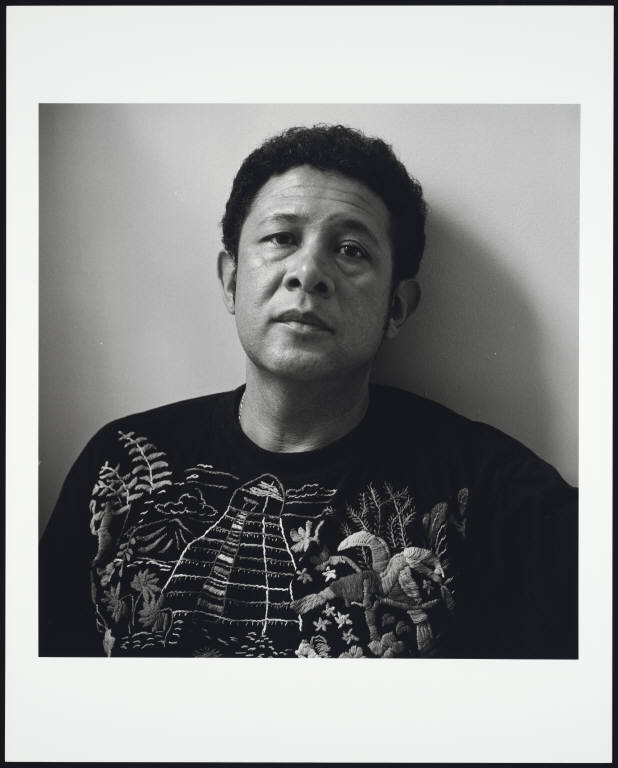

Jaime Manrique

by Edith Grossman

BOMB 121/Fall 2012

I first met Jaime Manrique roughly 30 years ago, and we’ve been friends ever since. I’m not sure I remember the precise circumstances. I think we both attended a poetry workshop run by Enrique Lihn, the late Chilean poet, at the Americas Society, though Jaime remembers our meeting as we danced to salsa at somebody’s party. Regardless, I was attracted by Jaime’s good-natured charm, sharp intelligence, and poetic talent, and after all these years, I still find those qualities extremely appealing.

He was always very kind to my son, Matt, who was a little boy when Jaime and I became friends and has always adored him. As a matter of fact, Matt met Terry Marks, the woman he eventually married, at a party given for Jaime by his late partner, Bill Sullivan. I’ve always cherished that connection between my son and a dear friend.

Our friendship has not been exclusively sentimental. I’ve also had the professional pleasure of translating a good number of his poems. An aspect of his poetic writing that I admire very much is his use of ordinary, colloquial language to create images of great beauty. An example is his short memory poem called “Mambo,” in which he remembers his aunts dancing the mambo “wearing their spike-heeled shoes, / lowcut dresses and wide swirling skirts; / their long obsidian hairdos / in the style of the time.” I’d venture to say that this quality may well be the effect of a profound and on-going North American influence on his poetry. One thinks immediately of William Carlos Williams, for example, or even Jaime’s beloved Emily Dickinson. Of course there are colloquial, imagistic poets in Spanish—Federico García Lorca and Pablo Neruda immediately come to mind—but it occurs to me that this may be an area that reveals the significant effect of the English language on Jaime’s work, even though he normally composes his poems in Spanish.

His novels, however, are written in English, and tend to have a larger historical focus, while his poetry narrows the point of view to a deeply personal one. Jaime’s fiction is meticulously researched and wonderfully revelatory of persons and events. His latest, Cervantes Street, explores the world of the man who despised Miguel de Cervantes and wrote a “continuation” of part one of Don Quixote before Cervantes could publish part two. A lucky misfortune, since the existence of what is known as “the false Quixote” allows Cervantes to explore the relationship between fiction and reality in the authentic part two in a way that is positively mind-boggling.

I enjoyed the interview with my old friend, especially the chance to talk to him at length about literature in general and his writing in particular.

No comments:

Post a Comment