Marco Bohr

Voyeurism in the photographs of Hisaji Hara

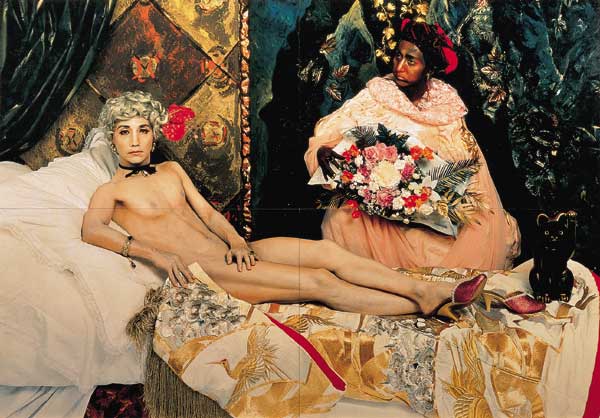

The provocative paintings of the French-Polish artist Balthus are the starting point for Japanese photographer Hisaji Hara’s visually arresting photographs currently on display at the Michael Hoppen Gallery. Like in Balthus’ work, the photographs are deeply voyeuristic, sexually suggestive, and fetishistic. As their titles indicate, the photographs are a study of’ well-known Balthus paintings that Hara generously appropriated from. Here, particularly in the context of Japanese photography, Hara appears to walk on well-trodden territory. In his acclaimed series Self-portrait as Art History, Yasumasa Morimura similarly appropriated iconic images from Western culture in his photographic montages. Rather than trying to match the original image as closely as possible however, Hara used Balthus’ work as a template, or a source, to produce photographs that are visually complex and culturally loaded in their own right.

The re-occurring motif of the Japanese schoolgirl in Hara’s work is less a reference to Balthus’ preference for young girls in his paintings, but rather, it more likely refers to the fetishistic value ascribed to the schoolgirl (and her uniform) in the context of Japanese culture. While this fetish is historically located in Japan’s troubled transition to a modern nation-state, it is intriguing to note that Hara’s photographs, in spite of being produced within the last two years, purposefully look aged.

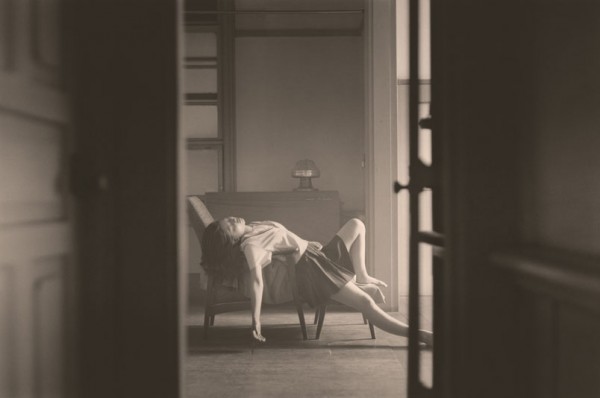

Hisaji Hara, A Study of the ‘Portrait of Therese’, 2009 and Margrethe Mather, Florence Deshon with Fan, 1921

The vintage quality of the photograph is achieved in a number of ways. Firstly, the prints are black and white pigment prints which have a brown tinge to them. The location for Hara’s photographs too, a derelict privately run Japanese medical clinic from the 1940s and 1950s, creates the atmosphere of a bygone era. In addition to that, Hara’s portraits are produced with a large format camera, which inevitably has a more narrow depth of field and subjects fall out of focus more easily. The soft focus in Hara’s photographs immediately brings to mind Pictorialism – an aesthetic movement that dominated photography in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Apart from creating images that look purposefully aged, the optical devices applied by Hara also contribute to the voyeuristic dimension of his gaze. In A study of ‘The Salon’, Hara appears to change the focus of the camera, comparable to the cinematic technique of split-focussing, by using multiple exposures. Like the masculine gaze naturalized by the cinematic apparatus, Hara’s focus is highly selective, voyeuristic, even intrusive.

The apparent voyeurism is further emphasized by photographing his subjects from low vantage points, from a distance, or through open doors and windows. The door or window frame at the edge of some of Hara’s photograph are poignant references to the framing of the photograph: a process in which visual information is not only included, but also excluded. In other words, the door and window frames function as an allegory for the dialectical relationship between inclusion and exclusion so elemental to the act of photographing. Hara’s photographs are however less about the process of photography than they are about the process of looking. Here, Hara appears to tap into a lineage of photographers such as Kiyoshi Yoshiyuki or, more recently, Noritoshi Hirakawa, whose work deconstructs and problematizes the act of looking itself.

In A Study of ‘Because Cathy taught him what she learnt’, Hara thus sets out a complex scenario in which the apparent voyeuristic nature of the image comes to the fore: though his eyes are hidden by a hat, a young man can be seen looking at a girl kneeling on the floor. His downward gaze is emphasized by his body diagonally leaning forward on a chair. Hara meanwhile, the apparent stage master of this scenario, produces a photograph which is being looked at in context of the gallery. These multiple levels of looking are completed in the realization that the young woman – the clichéd object of the photographer’s gaze – is knowingly looking straight back at us.

If you are interested in Japanese photography, please download my essay:

Marco Bohr (2011). ‘Are-Bure-Boke: Distortions in Late 1960s Japanese Cinema and Photography’. Dandelion Journal. Vol. 2, No. 2.