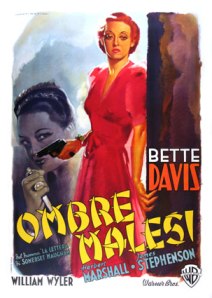

At night on a Malaya rubber plantation a gunshot rings out. A man stumbles out of a bungalow, pursued by a woman, who empties all the chambers of her revolver into him. The moonlight reveals a distraught, gun-toting Bette Davis – this is the unforgettable opening of the 1940 version of The Letter, adapted from Somerset Maugham’s celebrated short story and play, which had been filmed several times already.

The following review is for the British Empire in Film Blogathon hosted by Phantom Empires and The Stalking Moon; and Katie’s Book to Movie Challenge at Doing Dewey.

“I think what has chiefly struck me in human beings is their lack of consistency” – W.S. Maugham in The Summing Up (ch. 17)

This is a story of murder, blackmail, infidelity and racial prejudice but not a whodunit – right from the opening seconds we know that Leslie Crosbie shot and killed the handsome Geoffrey Hammond on the veranda of the bungalow where she lives with her husband Robert on their plantation in Malaysia (or ‘Malaya’ as it then was). She claims that the man had made improper advances and that she was only acting in self-defence. The case is brought to trial in Singapore but the marriage is put under great financial and emotional strain once a letter is offered for sale that makes it clear the murdered man did not, despite what Leslie first said to her lawyer Joyce, turn up drunk out of the blue, but had in fact been invited …

Maugham’s complex upbringing – orphaned at an early age and educated abroad, he studied medicine back in the UK before his success as a novelist and a dramatist initiated a change in career – as well as his homosexuality, at a time when this was illegal in most ‘civilised’ countries, may have helped give him a special feeling for depicting outsiders. The Letter is a good examples of this – one of his many stories set overseas during Great Britain’s colonial era, its presentation of conventional people overcome by passions they can’t properly articulate in faraway places, provides a fascinating if oblique reflection on the British character and the petty jealousies and hypocrisies that can drive people, no matter where they live.

“He tried to rape me and I shot him” – 1927 stage version

The 1940 film version (one of many – see below) offers a great part for Davis (despite a pretty dodgy British accent) as she sheds her layers of propriety slowly but surely, haunted by her passionate act of murder illuminated by moonlight. Director William Wyler apparently shot the memorable opening dozens of times, though ultimately the studio opted for the first take. Either way, it is highly dramatic and atmospheric as Tony Gaudio’s camera prowls the plantation (well, the studios at Burbank) before the gun starts to go off. The British community rallies round Leslie and her husband, the nice but dull as latex Robert (Herbert Marshall) – but her lawyer Howard Joyce (a great performance by James Stephenson, another good actor that died far too young) starts to suspect that she is not telling the truth. In Columbo-like fashion, he picks up on several inconsistencies. As he says in the original short story:

“If your wife had only shot Hammond once, the whole thing would be absolutely plain sailing. Unfortunately she fired six times.” – 1926 short story

Maugham had in fact first sketched out the narrative for his hugely popular 1927 three-act play the previous year in his eponymous short story, which is told from Joyce’s point of view and begins with Leslie already on trial. It is otherwise very close to the play, and maintains much of the same dialogue too, albeit without its celebrated closing line:

“With all my heart I still love the man I killed.”

What drives the play is the slow reveal of Leslie’s character, her hidden passions and the deceptions she has perpetrated on her husband and, less successfully, on her lawyer. She is lionised by the expat community during the trial for her stoical reserve, refusing to give in to despair. Unlike her husband she is a tower of strength, attending to her fine lace work and seemingly standing up for all the right virtues and values in a land full of heathens. What gives this a sting though is the revelation of ‘another woman’ in Hammond’s life, who in this case is actually the wife. What makes her ‘other’ is that she is a local woman, something the conservative expat community predictably rejects – in an unguarded moment Leslie damns her for being overweight and un-attractively adorned in bangles, revealing her jealousy. Leslie is driven in fact by racial prejudice as well as sexual jealousy, but this is not revealed until the final scene in which we find out what really led to the shooting.

In the story and play Hammond’s wife is Chinese but in the 1940 film – as per the racist studio practices of the day – she becomes Eurasian and is played under heavy make-up by Gale Sondergaard, who was of Danish extraction … She is presented pretty much as clichéd dragon lady, which is infuriating not least because it completely muddies Maugham’s original intentions. Leslie knows nothing about the woman, just hates her because she is married to the man she lusts after and because she believes he has married racially beneath him. In the film Mrs Hammond, as she is billed, is presented as a Fu Manchu yellow peril-style caricature and ultimately as a murderess, though reshaping the narrative as essentially a duel between the two women (Leslie in this version meets her by going to collect the incriminating letter with Joyce) is a very smart idea that pays off in the beautifully shot moonlit finale that is designed as a counterpoint and echo of the opening sequence. Interestingly, the ending was prepared in two distinct versions, just like the original play. As released, Davis admits her feelings for Hammond to her husband and then heads into the moonlit garden to meet her destiny at the hands of the dragon lady, while her return home party continues unaware. In the alternate re-shot and re-edited version, that was ultimately unused, Davis is made more sympathetic by not bothering with her final confrontation with her husband.

“He tried to male love to me and I shot him” – 1940 film version

The play was first performed in London in 1927 at the Playhouse starring Gladys Cooper and Nigel Bruce, and in New York later the same year at the Morosco Theater with Katharine Cornell. For the finale as originally performed, Maugham flashes back to before the opening scene to explain why Leslie shot Hammond. In the published version of the play, Maugham opted to just have Leslie relay it all verbally – both versions are presented in most editions. The play’s success lead to the first of several film version in 1929 starring the ill-fated Jeanne Eagels, with Herbert Marshall playing the man she shoots – in this version the narrative is presented in completely linear fashion, so the concluding flashback now makes up the first 15 minutes of the film. At the time the studio also made several foreign language versions, more or less simultaneously, for overseas markets (this is before dubbing became the norm). Thus Paramount also released alternate adaptations shot in French (La Lettre, 1930), German (Weib im Dschungel, 1931), Spanish (La Carta, 1931) and Italian (La Donna Bianca, 1931). You can read what Flickchick has to say about the 1929 version over at Person in the Dark, which is also participating in the blogathon.

Since 1940 the play and story have been adapted several times for radio and television – most notably the 1982 TV-Movie remake of the Davis version for ABC starring Lee Remick. Herbert Marshall, who played the victim in the original version and the woman’s husband in the 1940s remake also has a link with the 1982 TV version as his daughter Sarah Marshall also took a supporting role. Incidentally, Marshall actually played a Maugham-like character in the movie version of The Moon and Sixpence (1942) and the author himself in the 1946 version of The Razor’s Edge.

Feature-length adaptations for film and TV include:

1929 – The Letter – starring Jeanne Eagles, Herbert Marshall

1929 – The Letter – starring Jeanne Eagles, Herbert Marshall- 1930 – La Lettre – starring Marcelle Romée

- 1931 – Weib im Dschungel– starring Charlotte Ander

- 1931 – La Carta – starring Carmen Larrabeiti

- 1931 – La Donna Bianca – starring Matilde Casagrande

- 1940 – The Letter – starring Bette Davis

- 1947 – The Unfaithful – starring Ann Sheridan

- 1956 – The Letter (BBC TV-Movie) – starring Celia Johnson

- 1982 – The Letter (ABC TV-movie) – starring Lee Remick

I thought this material would be suitable for the the British Empire in Film Blogathon hosted by Phantom Empires and The Stalking Moon as Maugham based it quite closely on the facts surrounding a real-life scandal from 1911. In Kuala Lumpur Ethel Proudlock, the wife of an expat British schoolmaster, was found guilty of shooting a man who had come to visit her while her husband was away. The verdict outraged British colonial society and ultimately she was pardoned and ended up settling in America after separating from her husband.

DVD Availability: Warner released a handsome-looking DVD many years ago which also includes the alternate ending and two radio adaptations starring Davis, Marshall and Stephenson – the 1941 broadcast can be accessed here. The 1929 version has now also been released on DVD.

The Letter (1940)

Director: William Wyler

Producer: Hal Wallis

Screenplay: Howard Koch

Cinematography: Tony Gaudio

Art Direction: Carl Jules Weyl

Music: Max Steiner

Cast: Bette Davis, Herbert Marshall, James Stephenson, Gale Sondergaard, Victor Sen Yung, Cecil Kellaway, Frieda Inescort, Elizabeth Inglis

No comments:

Post a Comment