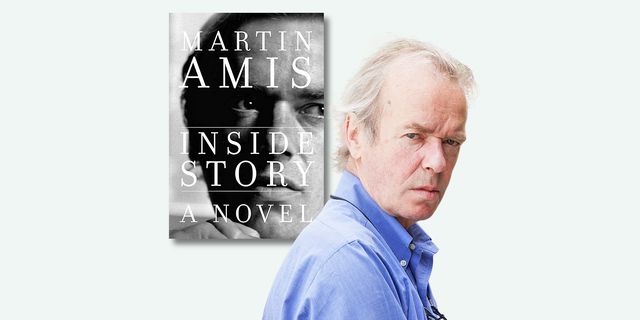

BOOKS OF THE YEAR

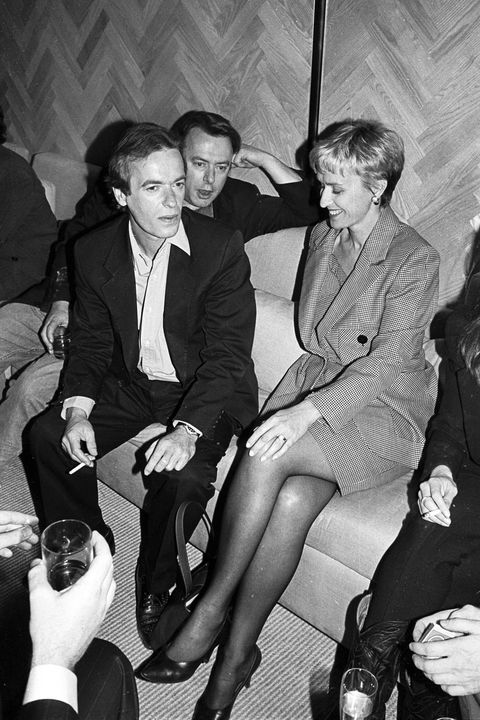

What Martin Amis Really Thinks About ... Everyone

Prior to the release of his latest novel, Inside Story, the literary agitator doesn't hold back about everyone from Tolstoy to Margaret Thatcher to the French.

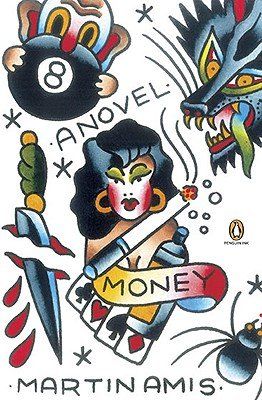

There's consistency to a Martin Amis novel. Whether it's Money, London Fields, or the dozen others, you can reliably expect a transgressive take on Western culture, peppered throughout with black wit. Plenty of smoking, a bit of sex, and deep pleasures on the level of the sentence. Ruminations on apocalypses global and personal. Amis' newest novel, Inside Story—also his longest—is something of a surprise, then, unlike anything Amis has written. It's unlike anything anyone has written.

There are autofictional portraits of his long friendships with Christopher Hitchens, Saul Bellow, and Philip Larkin, with moving accounts of their passing. There's a memoir of his affair with the ribald Phoebe Phelps, who may have seduced his father, the novelist Kingsley Amis—and who does not exist. There are interstitial chapters on writing fiction, with lines like, "Keep an eye on the suffixes; maintain a safe distance between words ending (say) with -ment, or -ness, or -ing; and the same goes for prefixes, for words beginning (say) with con-, or pre-, or ex-. Try it. You'll notices that the sentences feel more aerodynamic." Oh, and it's a study of 9/11. And Jewish statehood. And Trump.

Above all, Inside Story is the 71-year old writer's death-haunted ode to life, arriving at a time of pitched outrage and discrete mourning. Esquire spoke with Amis over Zoom a few weeks before the U.S. publication of his new novel. He dialed in from his vacation home on Long Island, where he has alternated with his residence in downtown Brooklyn.

Esquire: Inside Story is valedictory in the obvious ways—losing Hitchens in 2011, Bellow in 2005, Larkin in 1985—and also a form of goodbye to your own writing. Did you see it as a summation while you were working on it?

Martin Amis: A summation and, I suspected, a farewell. I don't think I'm going to write another long novel. But it sort of came upon me. It wasn't there at the beginning. But six years later it was clearer and clearer this wasn't going to go on forever. Then it did become very valedictory, especially that last section, the "Postludial" section. And full of regret. Because there are pains you have to go through when writing a novel. If I wrote a novel without that—where it was all flowing, from beginning to end—it would make me very suspicious. It has to have the admixture of pain. But otherwise it seems to me a hilariously enjoyable way of spending one's time. Assigning life to all these propositions, and (usually) dreaming up people, rather than taking them from life.

There is a bit of that in the novel. The Phoebe Phelps character is completely invented. I thought I needed the variation. There's something very limiting about writing about real people. I'm still in a permanent state of amazement that Saul Bellow managed to do it so successfully, in four of five of his novels, where people I know were dragooned into it. But as I say in the course of the book, his concentration of detail—he gets so much more out of a looking at a human face than I do or, you know, almost everyone else does.

I never suspected my subconscious was active when I was writing my early novels. But you do notice it when you come up against a difficulty. When I was younger, I used to just press on and give myself a terrible month trying to force myself past this difficulty. Usually what I ended up with was a chunk of pages that I eventually cut. Salman Rushdie talks about a novelist's bullshit detector, where you can sort of fool it for a bit, but it presses in on you eventually. But sometimes you come up against a difficulty—and if you're familiar with your subconscious—you just walk away from it. You may need to sleep on it, and you may need to sleep on it more than once. It's a waste of time to just batter at it. And if it comes, it comes. You're suddenly back at your desk without having felt any revelation or epiphany, but the difficulty is over. That is the closest to a magical experience that you will get when you're writing. Just leave it alone and let it resolve itself. That is the most joyful part of writing.

There was none of that with Inside Story. Except with the invented parts.

ESQ: You've written here and elsewhere about taking the aerial view of the novelist's career, whether it's Bellow's or Nabokov's…

MA: It's handy sometimes to think of writers in terms of their strike rate. Nabokov's is amazing: eighteen novels, perhaps twelve masterpieces. I can't think of any other writer who approaches that. Trollope perhaps.

ESQ: He wrote, what, thirty novels?

MA: Forty. But this is the killer: The Way We Live Now, which is half as long again as my recent novel, he wrote in six months.

ESQ: That's incredible.

MA: It really is incredible, when you think of the powers of organization needed to orchestrate that.

ESQ: Perhaps it comes down to brain chemistry. In twenty years, they'll find the chemical that helps a writer hold the novel structure in their head. And Trollope had a surfeit of it.

MA: Yes, exactly. In discussions of Updike and Anthony Burgess—who was also incredibly productive—they call it "pressure on the cortex." It is a sort of condition. And it's certainly what you begin to lose, the power to organize a long novel.

ESQ: Burgess said he had only one unfinished novel. Is that similar for you? Any half-finished projects over the years?

MA: A couple of wobbles. I abandoned a novella early on in my life. I very nearly abandoned Inside Story, or at least I had two or three goes at it and couldn't find a tone, or the right space, the right distance from what I was writing. This took six years. It does come down to energy. Energy of the most productive kind, the most channeled energy. It weakens as you get older. Of course, Trollope was dead by the time he was my age.

I wrote a memoir twenty years ago, and that came at twice the speed of normal fiction. Because there was nothing to make up. It's really humble transcription, rather than imagination. This turned out to be a sort of mixture. Scenes and events that really did take place, with a little soupçon of imagination. But having committed myself to just transcription [with Inside Story], I did need imaginative holidays from that. I seem to have got it with the Phoebe Phelps character.

ESQ: The novel has an embedded "How to Write Fiction" guide. I wondered how that came about.

MA: I wonder too. But that's part of the valedictory side of it. Having written so many novels and other books, it seems to me I've learned a few ground rules and guidelines. I've always been fascinated by how to modulate and use certain techniques.I used to say there's a useful separation that can be made between a writer's talent and a writer's genius. Every writer who's been published more than once or twice has a little bit of genius. No question in my mind that that's true. Talent is more about technique. Of course, you can't teach genius, but you can teach talent up to a point.

It also should be noted, my position as an extremely privileged observer of the literary life, which began before I was ten years old. I, having had this privilege, should pass it on in some form or other. It still strikes me as a fascinating, mysterious profession, with this magical element of creation. I ought to know, by now, a bit about it. I wanted to pass that along.

ESQ: How are you feeling as we head into the election?

MA: I've seen photographs of women in early and middle age sobbing as they pray for Trump. My imagination fails. I can't see anything positive to latch onto. It's a dreadful spectacle. His clinging to the idea that he's "super smart." I don't know anyone even of average intelligence who goes on about how smart they are. Doesn't come up, does it?

ESQ: It's like a terrible poker tell.

MA: Yes. I had a friend whose heart beat so heavily when he had a good hand you could feel it at the table.

ESQ: Every interview asks about your father, but it seems your late stepmother Elizabeth Jane Howard was also influential in your writing life.

MA: I had a terrific relationship with my father. Christopher Hitchens said it was the best father-son relationship he'd ever seen. I think there was a peculiar reason for fathers and sons not getting on in my generation, and it's very simple: the sexual revolution. The fathers were looking at their sons—and this was the case with Christopher—and they're thinking, "What was all this no sex before marriage?" They see their offspring going very much against that rule.

My father was an exception. His sex life was promiscuous, really got going after he got married. It was adultery. That was their sex life. It presupposes the married state. But as of 1970 suddenly it wasn't like that anymore.

Kingsley had that fight with his father, when his father found a letter from a married woman in one of Kingsley's suits. They had a huge row about that. It was pure envy on the part of the father. So he'd had that fight with his father, he wasn't going to have it with his son. And also any promiscuity excited my father. Though I never saw him being less than courteous to women. And it's not the case that someone said, "Did he make passes at your girlfriends"? No. I think he fancied one or two of them. But he certainly would not have taken it further than that.

So the deck was clear for my brother and I to have sex lives unfrowned on by my father or Jane. And it's different for daughters. But a permission was given, in the broadest sense. And that ensured a very close relationship with him. It was a good father-son relationship.

Also one of my greatest literary friendships. We talked about what I talk about in the book: technique, the subconscious. It's very interesting, because we wrote such similar sorts of novels. I always thought if he had been born a generation later, he would have written my novels. And if I'd been born a generation earlier, I would have written his novels.

ESQ: You've said if you had written The Old Devils [Kingsley Amis's Booker Prize-winning novel from 1986] in your sixties, you would have considered that quite a success. What are your feelings about Inside Story? Are you too close to it to think in those terms?

MA: It's an interesting question. When I finished it, I didn't dare to think about that. I would have said, as people like Trump and Chris Christie think it's worth saying, "It is what it is." I was trapped as a kind of helpless onlooker. Only now am I able to like it, when I pick it up. I'm never going to be able to read it straight through. There are bits that I read. It's all at a pretty high standard—that's as much as I allow myself to think.

ESQ: Blake Bailey's authorized biography of Philip Roth will be published this spring. Did that ever have interest for you? Granting an authorized biographer full access?

MA: Well, I did authorize a biography and instantly regretted it. It was nothing but trouble. That way vanity lies. It's better to have nothing to do with it at all. Don't engage any part of your mind in sprucing up your self-image. A waste of time.

ESQ: Would you retire like Roth?

MA: This is going to be the next big decision. I hope I go on as normal, more or less. Probably writing short stories rather than novels. There will come a day when you think what you're trying to do is actually not worth doing. Or so far off your better books…

ESQ: Your Rushdie bullshit detector will edge into the red.

MA: Something like that. Running out of fuel. I often think, how much of a tank has a writer got? That's what strikes me about Hilary Mantel. I met her decades ago, and I thought, big-tank writer. She's obviously got huge reservoirs of energy and expressiveness.

At the moment, what I dread more is just being wearied by describing things I've described before. Those annoying areas of human existence for which the vocabulary is limited. Describing someone laughing, for instance. There are only a few words for it. I'm not going to use guffawing, or chortle. There's only one good word for smiling, which is smiling. Leering is not bad. But I'm never going to use grinning. The vocabulary gets thin. And it's a chore to enliven it and de-banalize it. I can imagine getting weary of that. Otherwise it's joyous.

ESQ: No Clockwork Orange novel, with a new dialect or a devolved vocabulary?

MA: No, nothing experimental. I have no patience for anything experimental or obscure—above all, obscure. I have to know at all times exactly what's going on. It's why I've been having such an agonizing time trying to scale the great fortress of Faulkner. I'm very committed to the pleasure principle. You read literature to have a good time. Or why else would people go on doing it?

ESQ: We're simple creatures.

MA: There have been fads for difficulty, almost like a marching song, this idea that we like difficult novels. I thought that was Lionel Trilling who said that, but it wasn't. And it's not true. I don't think we do like difficult novels. We thought we did, for a bit. But we don't like them anymore.

ESQ: It can be an age thing. I was able to breeze through Gravity's Rainbow when I was twenty. Now not so much. I need it go down a little smoother.

MA: Pynchon's a good example, where you don't really know what's going on half the time. David Foster Wallace, too. I don't really read my juniors much. Occasionally I'll have a great time with one or another. Zadie Smith's NW, I thought, was terrific.

I think social realism is all there is. I'm all for diversity and variety. In principle, let them write difficult novels and experimental novels. I'm not going to read them anymore. You have a great tolerance for it when you're young. You feel proud of yourself. What is the average tolerance for Infinite Jest? Two hundred pages, in my case.

ESQ: Will there be another public intellectual like Hitchens? Zadie Smith could develop more and more into one. It's a short list. There's Ta-Nehisi Coates.

MA: He can be very funny, too. It is a short list. Quite narrow. There are very few people like Hitchens who can talk competently about politics, about literature, about history. That renaissance man or woman idea has shrunk, markedly. It's not something you set out to be, a public intellectual.

ESQ: Nor is there as much space for a dedicated contrarian.

MA: Christopher was a real contrarian. One of things I'm proud of is that friendship. We never had even the slightest froideur about disagreements. I think it's a good rule never to lose a friend over an argument. Never get into these sincerity contests: "I feel so strongly about this that I never want to see you again." Rubbish.

I disagreed with Hitchens violently over literary things as well as political things. But it never got to the point of raised voices. That's partly because real friendship is rare, particularly male friendship. My father lost a dozen really excellent friends over the Vietnam War, because he was a hawk. A ridiculous position to take. Let alone to lose friends over that.

Perhaps I had much firmer guard rails. Christopher fell out with other friends over politics. I thought, I'm not having that. You mustn't self-dramatize your righteousness or your sincerity. That never happened between him and me.

ESQ: Hitchens would have been heartened by the resurgence of socialism in the U.S.

MA: The first time I saw Christopher on American TV, he was up against someone who was very obviously a narcissist. He had bright green eyes and he was wearing a bright green suit of exactly the same hue. It was in the Reagan era, and this green-eyed monster said, "Would you describe yourself as a liberal?" Liberal then had the connotations of a leper. And Christopher said, "No, I'm not a liberal. I'm a socialist." That succeeded in shutting up the guy, in dumbfounding him. I admire Hitchens for saying that. It was so against the grain at that time.

I'm secure in my conviction that socialism doesn't work, because it goes against human nature. The idea of people acting out of social altruism is not part of human nature. It's an element in it, but it's not a guiding principle. I've always been a gradualist. Certainly there's a lot of ground the Democrats could usefully incorporate along socialistic lines. Get America past their phobia about it.

ESQ: You've said you're a dedicated gynocrat. Here we are with two male septuagenarians at the top of the ticket. There's Kamala Harris, which is progress. Are you feeling confident we'll elect a female president in 2024?

MA: In 2016, a Trump supporter said, "Trump might give us nuclear war, but anything's better than Hillary." When nuclear war is a happier outcome than the election of your first female president, you can tell something has gone wrong, and far back. There have now been about fifty or sixty heads of state who were women. Hillary Clinton, alas, tried to be a tough guy: "I would blow Iran off the map if they did that." Margaret Thatcher's another example of a brawny woman without obvious feminine qualities.

ESQ: Except to Hitchens, who thought she was a minx.

MA: Yeah. Angela Merkel, I met her briefly once. I was in Tony Blair's entourage so that I could write a piece about Blair. I thought, there's a woman leader who is leading like a woman. Not pretending to be just as tough as a man. I was in Germany in 2015 where she made the decision to allow the entry of a million immigrants from the Middle East. The slogan was wir schaffen das: "We can do it." Everyone thought it was going to destroy her politically. It weakened her, but she's still there. She grew up in the totalitarian heart of Germany, she knows how high the stakes can be. But she never lost that feminine clemency. I still very much admire her. Jacinda Ardern too, but the challenges in New Zealand are not the same as the largest economy in Europe. And with such an appalling history. I meant what I said about Germany's effort to get past that, to get out of that. I think we can expect great things from female leaders. But not yet in America. For some reason.

ESQ: There was a Guardian article recently saying that two-thirds of people age 18-39 didn't know six million Jews were killed in the Holocaust. There's a fear of this knowledge being lost. You note that Germany did a good job of looking inward and working through this history, and France didn't.

MA: I'm quite anti-French on some level. I can't bear the posturing of negativity, like with Sartre. It's a little hard on the French to say they never made any effort. It's paltry compared to Germany, sure. You can measure the German effort in that the young people want to talk about it. They want to take it on. I never got that feeling in France. Although, my second book about the Holocaust [The Zone of Interest], which came out in 2014, that was very well received in France and not at all well-received in Germany. The Germans somehow picked up the notion you can't be serious and funny at the same time. Every novel worth reading is funny and serious. Anyone who's any good is going to be funny. It's the nature of life. Life is funny.

ESQ: Geoff Dyer wrote that the older he gets, the more he just wants nonfiction. Have you seen changes in your own reading habits? Less fiction, more poetry?

MA: It's difficult to read poetry now. I used to read more poetry and prose when I was young. I'm certainly less interested in fiction as something to read. The trouble with poetry is that it stops the clock. It says, we're going to look at this moment and we're going to think about it. And one of the real truths of the 21st century, and earlier, is that history is speeding up. We're all on a sort of rollercoaster now. There are existential threats that weren't fully acknowledged not so long ago. We are sort of hurtling forward. It's more of a task to ask people to slow down. That's why the difficult novel is more or less doomed.

What I do is recite poetry to myself, from memory. My father knew all of major English verse by heart. And I know quite a bit. I also have a good memory for prose. I find I go over to check certain poems that are dear to me. And totally mysterious in its own way, the poetic art. My father and I always agreed poetry was a higher calling. I would always say there's a little bit of space between poetry and—lower down—fiction. Then an abyss before you get to drama. I think it's a great cosmic joke that Shakespeare was a poet, since he was the great universalist. He's the only playwright whose work has lasted far beyond his lifetime. After him, who's next on the list? Ibsen?

ESQ: Chekhov? Beckett?

MA: Racine?

ESQ: Moliere?

MA: In English poetry, there's wave after wave of genius. And in the novel, too. But drama has a pathetic legacy. Except for Shakespeare.

ESQ: Shakespeare's a good note to end on.

MA: Shakespeare will do fine. My father said once you can always tell a second-rate intellect by anyone who degrades Shakespeare, or downgrades him. When Tolstoy met Chekhov, he said, "I really love your stories. I would have been proud to have written 'The Lady with the Little Dog.' But as for your plays, they're even worse than Shakespeare." Crystalized stupidity.

No comments:

Post a Comment