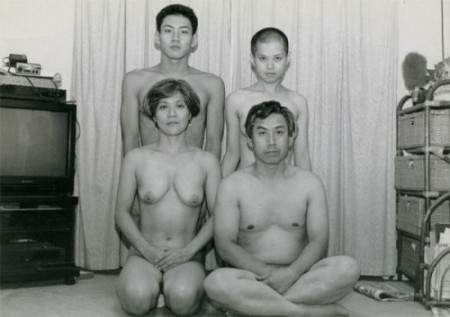

Yurie Nagashima, Kazoku, 1993

In a previous blog post, I wrote about the photographer Yurie Nagashima whose photographs of herself and her family in the nude instigated a dramatic shift in Japanese visual culture. After exhibiting her phenomenally successful Kazoku series in 1993, Nagashima continued to interrogate photographic subjects related to gender, sexuality, representation and the body.

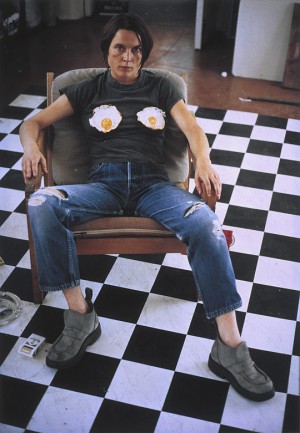

Yure Nagashima, Onion Boob and Sarah Lucas, Self-portrait with Fried Eggs, 1996

In one photograph, she holds an onion in front of her left breast while holding her t-shirt up by her teeth. This form of visual allegory and humorous photographic intervention locates Nagashima alongside artists such as Sarah Lucas who, in one photograph, placed two fried eggs in situ of her breasts. In the case of Lucas, the reference to female fertility and reproductive organs signified by the eggs is clear. In Nagashima’s case however, the onion is more difficult to locate since it does not immediately signify either the male or the female body. Instead, the onion might refer to the trope of perfectibility: the emphasis on aesthetic perfection of fruit and vegetable that is common in Japanese department stores. The perfect watermelon, the perfect carrot, the perfect onion, is, above all, determined by its symmetrical and even visual appearance. Nagashima’s photograph appears to question, even ridicule, this paradigm closely associated with consumerism and the representation of gender. Here, I am referring to consumerism in an economic sense but also consuming food as metaphor for consuming the female body. The onion thus functions as a pun on consuming and being consumed: in contrast to the soothing milk of the mother’s breast, Nagashima purposefully chooses a vegetable known not only for it’s acidic taste, but also, for causing tears. The unpeeling of the onion, and the allegorical pain associated with it, becomes the complete antithesis to the warmth associated with the mother.

Another photograph in which she has painted her breasts in the shape of two cartoon characters suggests that Nagashima’s preferred subject is her own body. Here, the body is not a neutral canvas or a corporeal ground zero, rather, the body functions as a potentially humorous even uncontrollable form explored by the camera. The physical act of taking a self-portrait is more closely located within the realm of performance art as Nagashima interrogates a corporeal and spatial interior by turning the camera on herself. In other words, the intervention takes places in Nagashima’s personal sphere via her body, while the camera acts as documentary device. Similar to the onion photograph, the cartoon characters serve as a visual pun that also acts to defamiliarize body parts. The cartoon characters have the effect of setting the photograph off from the classical iconography of the Nude and enabling it instead to act as asignifier for specific bodily functions. The defamiliarization of body parts also acts to desexualize the body as a whole. This visual methodology is perhaps most apparent in This Time, where Nagashima makes another direct gender specific reference to a bodily function. In his concept of the ‘grotesque body’, the literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin argued that references to bodily excrement can act as a powerful device to invert a hegemonic social order. The allegorical blood on the floor situates the body outside of stereotypical representations of the body in mass media, consumer culture or pornography, placing it instead within a discourse of necessity and privacy.

It is ironic that as much Nagashima explores narratives of private life in her photographs, she was herself in the meantime turned into a celebrity figure in Japan. For a period of time in the mid-1990s, newspapers, magazines, TV chat shows, and the so-called ‘wide shows’, relentlessly pursued Nagashima in hopes of featuring the up-and-coming artist in their programming. With the emergence of a number of women photographers in a relatively short time period, from 1993 until about 1996, critics referred to Nagashima as a leader of a ‘girl photography boom’. Nagashima fiercely sought to distance herself from this label and, in the process, became critical of the media attention that her work has provoked.

In as much Nagashima appears to engage in the pleasure of looking and being looked at in her photographic series Kazoku, in more recent photographs Nagashima’s gaze back to the spectator is noticeably absent. In one photograph, Nagashima’s back is literally turned towards the spectator. Viewed within the context of Nagashima’s resistance towards the increasing media attention, this gesture signifies her growing desire to be left unmediated. Even if this photograph relates to Nagashima turning away from the camera, from representation, from our gaze, she is still using her body to communicate this message. By performing to the camera, by deconstructing socially constructed gender identities, and by becoming object as much as subject of her photographs, the many bodies of Yurie Nagashima have reset the parameters of photographic discourse in her native Japan.

Please also read my post The Family Photos of Yurie Nagashima.

If you are interested in Japanese photography, please download my essay:

Marco Bohr (2011). ‘Are-Bure-Boke: Distortions in Late 1960s Japanese Cinema and Photography’. Dandelion Journal. Vol. 2, No. 2.

Marco Bohr (2011). ‘Are-Bure-Boke: Distortions in Late 1960s Japanese Cinema and Photography’. Dandelion Journal. Vol. 2, No. 2.

No comments:

Post a Comment