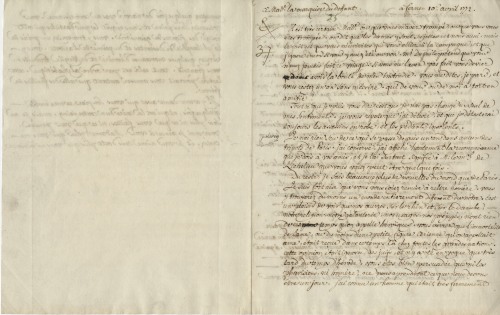

Letter from Voltaire to Madame Du Deffand, 1772

Francois Marie Arouet (21 November 1694 – 30 May 1778), better known by his nom de plume, Voltaire was a French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher. He was a polarizing figure whose personal indiscretions invited societal censure while his strong political positions and support of civil liberties put him at odds with the French authorities, resulting in two periods of imprisonment and a period of temporary exile. Voltaire tried his hand at nearly every literary form, and wrote over 20,000 letters. One of which is preserved in the Frances W. and H. Jack Lang Letter Collection.

The letter from Voltaire to his friend Marie Anne de Vichy-Chamrond, marquise du Deffand, reproches the lady for for not having written in some time. Madame du Deffand was know to be an intelligent woman, a friend of intellectuals and a patron of the arts. Voltaire goes on to offer his observations on the writings of Homer and on immortality. He suggests that Madame du Deffand have read to her (she was then blind) articles by Homer, Descartes, and Virgil and Ariosto’s poems in the Encyclopedia, edited by himself, Diderot and D’Alembert.

Voltaire, Francois Marie Arouet de. Letter, signed “v,” 2 ½ pages 4to. Ferney, April 10, 1772, to Madame Marie Du Deffand, Marquise de Vichy.

[Translated and transcribed.]

To Madame la Marquise Du Deffand at Ferney

April 10, 1772

It is quite certain, Madame, that either you have deceived me or else that you are in error. It is sad that ladies are subject to this and so are we. but the fact remains that you wrote you were going to the country, and that I am still unaware of whether you have been there or not. Mr. Dupuits claims that you never undertook the trip. If you have not done so you should be so kind to inform me of that fact. You tell me “I am leaving” and you remain a full year without writing me. Who then between you and me is guilty in our friendship?

All that I am able to tell you is that I have altered not one of my sentiments. I repeat that I have detested, and that I shall forever detest assassins of the robe, and insolent pedants.

I have no knowledge of what has been going on for the past year in any of the bawdy houses of Paris. I have kept, I have proclaimed loudly the gratitude I owe your friends and I have signified it particularly to M. the Marichal de Richelieu whom you may be seeing once in awhile.

Moreover I know more news from the North than from Paris.

I am greatly pleased that you have begun to reread Homer. You will find in him, at all events, a world entirely different from ours. It is a pleasure to see that our wars on the Rhine and on the Danube, our religion, our courtesy, our usages, our prejudices have nothing of what one may call heroic. You will see that the immortality of the soul, or at least the airy little form which one called soul, was accepted in those times in all the great nations.

This belief was unknown to the Jews and was in vogue only much later at the time of Herod. You are quite persuaded that neither the Pharisees nor Homer will teach us that which we must someday become. I know a man who was more ridiculous than to suppose an infinite being governing a finite being, and governing it very badly. He added that it was very impertinent to join the mortal to the immortal. He said that our feelings are as difficult to understand as our thoughts; that it is no more difficult for nature, or to the author of nature, to give thoughts to an animal on two feet called man than to give sentiments to an earthworm. He said that nature had so arranged things that we think by our head as we walk by our feet. He compared us to a musical instrument which, once broken, no longer renders a sound. He pretended that it is of the final evidence that man is like all other animals and all plants and perhaps like other things in the universe, made to exist and then to exist no more.

His opinion was that such an idea consoles one of all sorrows of life, because all these so called sorrows have been unavoidable. Therefore man having arrived at the age of Democritus would laugh as he did.

Consider, Madame, if you are for Democritus or for Heraclitus.

If you had wanted to have questions on the encyclopedia read to to you, you would have been able to see something of this philosophy even though it is a bit shrouded. You would have passed over those articles which would not have pleased you, and perhaps come across a few others which would have amused. Hardly had this work been printed that it became four editions even though it be little known in France. You would have found in it, at first hand, all those things you regret at times not knowing. You would pass painlessly without regret the few articles which demand geometric figurations. You would find a précis of Descartes’ philosophy and Ariosto’s poem. You would find a few pieces by Homer and by Virgil translated into French verse. All of that in alphabetical order. This reading could amuse you as much as FRERON’S leaflets.

There was a lady with whom you had supper, it seems to me, sometimes, and who is the mother of the co-signer but I no longer know what you are doing. Nor what you are thinking. As for me I think of you, Madame, more than you think; and I love you without a doubt more than you love me.

No comments:

Post a Comment