|

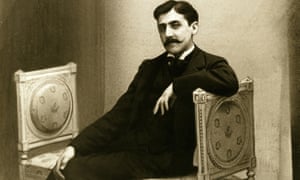

| Mysterious no more... Marcel Proust, photographed in the late 1890s. |

Lost Proust stories of homosexual love finally published

Written in the late 1890s but held back from publication, the nine tales in Le Mystérieux Correspondant are due out this autumn

Alison Flood Thuesday 8 August 2019

Nine lost stories by Marcel Proust, which the revered French author is believed to have kept private because of their “audacity”, are due to be published for the first time this autumn.

Touching on themes of homosexuality, the stories were written by Proust during the 1890s, when he was in his 20s and putting together the collection of poems and short stories that would become Plaisirs et les jours (Pleasures and Days). He decided not to include them.

In the 1950s, they were discovered by the late Proust specialist Bernard de Fallois, whose publishing house Editions de Fallois will publish them in French in October, 97 years after Proust’s death, under the title Le Mystérieux Correspondant (The Mysterious Correspondent).

The French publisher said the stories, which include a mix of fairytales, fantasy and dialogues with the dead, showed the source of Proust’s masterwork, À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time), which was published in seven volumes between 1913 and 1927.

“All of them remained secret, the writer never spoke of them,” said Éditions de Fallois.

“Proust is in his 20s, and most of these texts evoke the awareness of his homosexuality, in a darkly tragic way, that of a curse … In different ways, the young writer transposes, sometimes barely, the intimate diary he could not write.”

Proust never publicly acknowledged his homosexuality, going so far as to fight a duel with a reviewer who had suggested, accurately, that he was gay. “At the same time that Proust was eager to make love to other young men, he was equally determined to avoid the label ‘homosexual’,” writes Edmund White in his biography of the French novelist. “Years later he would tell André Gide that one could write about homosexuality even at great length, so long as one did not ascribe it to oneself. This bit of literary advice is coherent with Proust’s general closetedness – a secretiveness that was all the more absurd since everyone near him knew he was gay.”

Luc Fraisse, a professor at the University of Strasbourg, has annotated and edited the stories for the forthcoming volume, which runs to 176 pages and is intended to mark the centenary of Proust winning France’s most prestigious literary award, the Prix Goncourt, for À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs(Within a Budding Grove).

“A question arises from the start: why did Proust discard these texts from Pleasures, having mentioned them in the initial summary?” Fraisse writes. “Without doubt he considered that because of their audacity, they could have offended a social milieu where strong traditional morals prevailed.”

Fraisse said the dominant theme of the stories was the analysis of “the physical love so unjustly denied” that Proust writes of in À la recherche, “in terms that announce and foreshadow Sodome et Gomorrhe”, the fourth volume of the series in which the author tackles homosexual love.

“It’s therefore in part, under the veil of a transparent fiction, an intimate diary of the writer,” said Fraisse. “The awareness of homosexuality is experienced in an exclusively tragic way, as a curse. We don’t find, anywhere, those comic notes introduced here and there throughout In Search of Lost Time, which give the work all the colours of life, even in the darkest dramas.”

Nevertheless, Fraisse said that Proust had already, in the unpublished stories, found his “perfect mastery of expression”. “These unpublished pages don’t have the perfection of In Search of Lost Time, but they help us understand it better, but showing us what its beginning was,” he said.

An English translation has yet to be announced.

Proust died in 1922 at the age of 51, after pneumonia turned into bronchitis and then an abscess on the lungs. An obituary in the Guardian at the timenoted his “difficult and obscure” style, describing him as “a strange being”, “very pale, with burning black eyes, frail and short in stature”. But it acknowledged that “of all idols and masters of present-day literature in France he is most likely to have won a place which time will not take away”.

No comments:

Post a Comment