The Pacific Rim Divide of “Japan’s Modern Divide”

Note from the Editor: Photography exhibitions can have a significant influence on the course of future photographic work. As Eiko Aoki points out, both of the photographers she discusses were influenced by exhibitions they encountered. Once the temporal span of an exhibition has ended, its contents can continue to circulate, as part of a larger historical archive, in the form of a catalog. The exhibition “Japan’s Modern Divide” has a substantial catalog which includes writings by Judith Keller, Amanda Maddox, Ryuichi Kaneko, Kotaro Iizawa and Jonathan M. Reynolds, and translations of Yamamoto Kansuke poems by John Solt. In this form, the ideas generated by the exhibition can impact future work.

Exhibition Success in Los Angeles

If residents of Japan were to learn that in five months of 2013 more than three hundred sixty thousand people in Los Angeles went to see an exhibit featuring the work of two Japanese photographers, would they be surprised? Surprised or not, would they be able to name the photographers: perhaps Araki, Hosoe, Moriyama? Would they even have heard of the two?

This is the curious cultural schism that was exposed with the J. Paul Getty’s groundbreaking exhibit—“Japan’s Modern Divide: The Photographs of Hiroshi Hamaya and Kansuke Yamamoto”—that took the city by storm (visithttp://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/japans_moderndivide).

Put in a broader context, this exhibition came in the wake of several other, recent displays of Japan’s postwar art, especially the avant-garde, that have been organized in the United States, parts of Europe, and Japan since 2012. Among these is a major retrospective on the Gutai group, the radical collective that broke barriers of social life and art in the 1960s and 1970s; and one on Mono-ha, the group of artists who made large-scale sculptures using natural materials. Both got serious attention from Western museums and galleries.[1]

In a similar vein, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is now showing “Kitasono Katue: Surrealist Poet” (through December 1), featuring works by the avant-garde poet and graphic designer (1902–1978). In the sudden surge of interest in Japanese postwar art, that nation’s photography has been playing an integral part in the ongoing “discoveries.”

Particularly relevant in this boom was the Getty’s exhibition of the images of Hiroshi Hamaya and Kansuke Yamamoto (March 26–August 25, 2013). The two photographers hail from opposite ends of the artistic spectrum: Hiroshi Hamaya was a practitioner of social documentary photography; Kansuke Yamamoto was a driving force in the avant-garde movement, creating innovative photographs with an uncompromising spirit.

This article will focus on the dual phenomena of this exhibit’s unforeseen sensational reception in Los Angeles and, paradoxically, its almost complete neglect by the Japanese media.

Background

The show combines the seemingly mismatched figures of Hamaya and Yamamoto, but when looked at from the historical context of early-twentieth-century Japanese photography, it makes sense to juxtapose the extraordinary work of two artists who represent distinct trends during the era’s dramatic transformations.

The history of Japanese photography underwent a significant change in the 1930s. Up until the mid- to late 1920s, pictorialism, a soft-focused impressionistic style, prevailed. A reaction against the traditional pictorial-influenced movement that sought painterly scenic directions came with the rise of Shinkō Shashin (New Photography),[2] which was inspired particularly by concepts from the German New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit). The New Photography embraced the camera’s mechanical ability to create sharp and detailed images by using techniques such as extreme close-ups and an emphasis on perspective. Other pioneering techniques, photomontage and photogram, for example, were also introduced. Fueled by technical advances, the movement evolved into two opposing camps: one toward documentary photography and photojournalism, which focused on social realism, and the other pursuing experimental avant-garde practices that were strongly influenced by Western surrealism.

Hamaya and Yamamoto were products of their generation and emerged from this turbulent era of Japanese photography. Born during the Taishō era (1912–26), Hamaya (1915–1999) and Yamamoto (1914–1987) took opposite directions. Whereas Hamaya used a photojournalistic approach to document regional subjects and social issues, Yamamoto adopted experimental, avant-garde techniques to create innovative photographs, collages, and poems strongly influenced by European surrealism.

Japanese curators would probably not come up with the idea of putting these two photographers together because they tend to define artists and their works strictly within genre constraints. A parallel exhibit from a Japanese museum’s side might be to pair the Hungarian-born American photojournalist Robert Capa and the American surrealist Man Ray.

The result of placing the two photographers in their parallel chronological contexts was nevertheless a resounding success for the American audience. By reframing the history of mid-twentieth-century Japanese photography through Hamaya’s documentary style and Yamamoto’s surrealist viewpoint, the exhibit shed light on the development and characteristic features of Japanese photography.

Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, the wife and husband screenwriters, who have a formidable collection of vintage Japanese photography—including works by Hamaya and Yamamoto—were at the Getty exhibit opening. “Our first reaction [when we heard about the exhibit] was that it was an offbeat combination,” they wrote in an e-mail, “but we now understand that it is meant to represent two different and important approaches in Japanese photography—the realistic and the surrealistic.”[3]

The exhibit also provided a fresh perspective on the complexities of Japanese modern life, bridging the prewar, the war, and the postwar; the traditional and the modern; the urban and the rural; and the East and West as represented by Hamaya’s traditional bent and Yamamoto’s foreign influences.

Katz and Huyck expressed their satisfaction: “We were impressed by the scope of the exhibition. It [not only] presented a chronological survey of both photographers’ images, but also revealed each of the artists’ evolution and the unexpected directions their work would take over time,” they wrote. “We were surprised to see that Hamaya’s later work became more abstract and that Yamamoto’s photographs were often surrealistic views of real political concerns in Japanese society.”[4]

The Getty enjoys an international reputation for staging top-quality photographic exhibitions, but it came as a surprise that this large-scale show met with such undisputed acclaim. This is especially true when considering that Hiroshi Hamaya is not as well known as is the highly popular generation of Japanese photographers who followed him, such as Eikoh Hosoe, Daido Moriyama, and Hiroshi Sugimoto. As for Kansuke Yamamoto, he must be among the greatest unknown artists in Japan, and his work has been lingering in relative neglect for decades.

Judith Keller, senior curator of the museum’s department of photographs, suggested why the exhibition was so successful. “I think it’s partly a matter of it being photography,” she said. “Our photography shows here at the Getty regularly attract a very large audience. Also, I hope the popularity is a result of the quality of our photography shows as well as [this one] being an unusual show in that it consists of two people who we feel are very important to the history of Japanese photography. It is presenting not quite a retrospective but more of an in-depth view of each of them than has ever been shown anywhere.”[5]

Within the five months of its run, “Japan’s Modern Divide” attracted three hundred sixty thousand visitors. Back in 2001, when the solo show “Yamamoto Kansuke: Conveyor of the Impossible” was held at Tokyo Station Gallery, it had an audience of just nine thousand. The Getty’s exhibit—seen by forty times more people than the Japanese exhibit drew—is undoubtedly a huge step toward international mainstream recognition of Yamamoto’s work.

Two Styles

Hiroshi Hamaya, the son of a detective, was raised in Tokyo. After making aerial images for an aeronautical institute, he embraced photojournalism and became a freelance photographer. He spent his time strolling around Ginza’s back alleys and Asakusa, the center of Tokyo’s shitamachi (lower city) districts, taking photos of ordinary life and people, from street vendors and performers to the homeless. In 1939 he became interested in documenting traditional regional folklore and rituals that were on the brink of disappearing due to encroaching modernization. He chose Japan’s little-traveled west coast as a photographic destination, and over the next two decades recorded the daily lives and seasonal rituals of farmers and fishermen.

Fig. 3. Rice Harvesting, Yamagata Prefecture (1955), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Fig. 3. Rice Harvesting, Yamagata Prefecture (1955), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

For most contemporary Japanese citizens, especially the younger generation, Hamaya’s documentation of rural life on the back coast of Japan is more like a view of a foreign land than of a “Lost Japan” recalled with nostalgia. Interestingly, Hamaya himself felt and thought in a way how Japanese people feel today. Said Keller, during an interview, “At the time the pictures were made, it was not only Hamaya as a Japanese person who cared very much about the culture and also was avidly interested in this new field of ethnography, and it was also not only about recording the past. It was learning about something that was exotic for Hamaya.” She elaborated: “He talks about how peculiar it all seemed to him, but I think he made all the trips back to this remote area because he was fascinated by this Other culture, really. Because he had grown up in the middle of Tokyo—in Ueno—he was really a city boy. The back country was so entirely different from what he had grown up with.”[6] When the works of the two artists are juxtaposed, some of Hamaya’s images take on a surreal tone approaching Yamamoto’s sensibility.

Hamaya’s ethnographic projects, Yukiguni (Snow Country, 1956), followed by Ura Nihon (Japan’s Back Coast, 1957), were begun when Japan was heading for the Pacific War and were completed during the early postwar years. After the war, many photographers tried to capture the contrast between traditional Japan and its modernity, but Hamaya seemed intent on avoiding turning his lens on the modernized side of Japan. Instead, he chose to document the harsh life of rural agricultural and fishery communities in the remote provinces, initially staying away from the social issues of the postwar period.

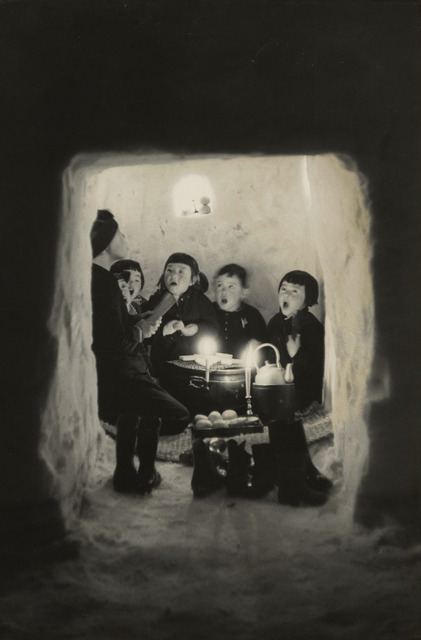

Fig. 4. Children Singing in a Snow Cave, Niigata Prefecture(1956), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Fig. 4. Children Singing in a Snow Cave, Niigata Prefecture(1956), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

In 1960, Hamaya covered the demonstration against renewing the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty (abbreviated Anpo in Japanese) from the perspective of the protesters by adopting an antigovernment stance. Ikari to Kanashimi no Kiroku (A Chronicle of Grief and Anger), the Anpo protest photo book, was published the same year. One of Hamaya’s Anpo protest pictures was picked up by the world news media and caught the attention of Magnum Photos, an international photographic cooperative.[7] Hamaya became the first Asian photographer to join the prestigious agency.

Fig. 5. The United States–Japan Security Treaty Protest, May 20 (1960), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Fig. 5. The United States–Japan Security Treaty Protest, May 20 (1960), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Fig. 6. The United States–Japan Security Treaty Protest, May 26 (1960), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Fig. 6. The United States–Japan Security Treaty Protest, May 26 (1960), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Although Hamaya gained international recognition by photographing the Anpo crisis extensively, he was disillusioned with the ineffectiveness of the protests and with politics in general, having witnessed the violent bursts of anger and hatred. He once again turned his attention to aerial photography, and recorded stunning vistas of nature in a number of places around the world. His career embraced ethnographic studies documenting rituals, the portraiture of artists, protest demonstrations, and nature without human interference.

Fig. 7. Yaichi Aizu, Poet, Calligrapher, and Japanese Art Critic(1947), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, Estate of Hiroshi Hamaya, Oiso, Japan.

Fig. 7. Yaichi Aizu, Poet, Calligrapher, and Japanese Art Critic(1947), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, Estate of Hiroshi Hamaya, Oiso, Japan. Fig. 8. Peaks of Takachiho Volcano, Kagoshima and Miyazaki Prefectures, Japan (1964), by Hiroshi Hamaya, cibachrome print, © Keisuke Katano, Estate of Hiroshi Hamaya, Oiso, Japan.

Fig. 8. Peaks of Takachiho Volcano, Kagoshima and Miyazaki Prefectures, Japan (1964), by Hiroshi Hamaya, cibachrome print, © Keisuke Katano, Estate of Hiroshi Hamaya, Oiso, Japan.

Kansuke Yamamoto was born in Nagoya. His father, Goro, owned a photo-supply shop and studio at a time when photography was practiced predominantly by the rich. Goro was also one of the founding members of Aiyū Shashin Kurabu (the Aiyū Photography Club),[8] a group of amateurs who advocated pictorialism. Yamamoto grew up surrounded by photography, but he was bored with pictorialism because of what he sensed was a lack of adequate stimulation. In 1933 he wrote in his dairy his impression of an exhibition held by the Aiyū Photography Club: “No works were unusual at all or showed anything progressive.”[9]

Nagoya had a thriving art-photography community in the 1930s, as the medium was transitioning to modernism. In 1931, “Doitsu Kokusai Idō Shashin-ten” (the German International Traveling Photography Exhibition)[10] was shown in both Tokyo and Osaka. It featured works by Man Ray, László Moholy-Nagy, and other pieces selected from “Film und Foto,” which had taken place in Stuttgart in 1929. The German exhibit had an immense influence on the New Photography movement in Japan.

In addition, in 1937 Shūzō Takiguchi[11] and Chirū Yamanaka[12] organized the seminal surrealism exhibition called “Kaigai Chōgenjitsushugi Sakuhinten” (Exhibition of Overseas Surrealist Works),[13] with the support of European surrealists such as André Breton and Paul Éluard. The show traveled to Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, Kyoto, and Kanazawa. As with the photo show in 1931, this exhibit introduced original works—mostly photographs—by Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, René Magritte, and Man Ray, among other surrealists, that most Japanese had seen only in magazines. This exhibition had a significant impact on Japanese artists, and it also left an indelible impression on the young Yamamoto.

As a teenager, Yamamoto was already developing an interest in both photography and poetry. From the beginning of his career, he drew artistic inspiration from surrealism, experimented with various photographic techniques, including collage and photomontage, and dabbled with painting and in three-dimensional forms. Amanda Maddox, assistant curator of the Getty Museum’s department of photographs, believes Yamamoto considered the relationship among his photographic, written, and three-dimensional works to be fluid.

“Yamamoto was not only a photographer but also a poet and many other things,” she said in an interview. “In the exhibit, you can see his paintings and three-dimensional work. He was a translator from French to Japanese, and I think it’s really important that he thought of everything as very interconnected and interrelated. You see excerpts from poems and you see texts incorporated into some of the images he makes. I think that is, in a way, how he is most original. He was someone who—throughout his career—thought about the relationship between so many different art forms and incorporated that idea into everything he did.”[14]

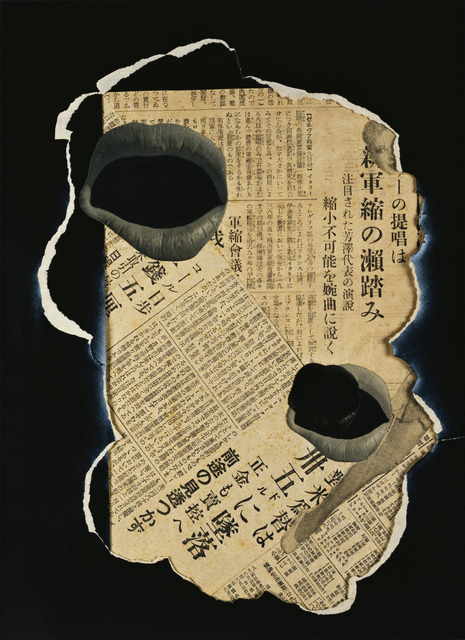

Fig. 9. The Developing Thought of a Human . . . Mist and Bedroom and(1932), by Kansuke Yamamoto, hand-colored photo collage, © Toshio Yamamoto, Nagoya City Art Museum.

Fig. 9. The Developing Thought of a Human . . . Mist and Bedroom and(1932), by Kansuke Yamamoto, hand-colored photo collage, © Toshio Yamamoto, Nagoya City Art Museum.

In 1931, at the tender age of seventeen, Yamamoto had already formed a photography group, Dokuritsu Shashin Kenkyūkai (Independent Photography Research Association).[15] The following year he created the hand-colored photo collage The Developing Thought of a Human . . . Mist and Bedroom and (1932), which combines newspaper clippings, three close-up images of lips, a woman’s leg, and a foreign woman’s face. Even as a teenager acquiring the skills to manipulate the methods of surrealism, Yamamoto was keenly aware of the movement’s potential as a vehicle for political and social commentary.

By the end of the decade, however, Japanese society was radically altered as a consequence of the nation’s accelerated militarization. With avant-garde and surrealist art often deemed subversive by the Special Higher Police (abbreviated Tokkō and referred to as the Thought Police), many avant-garde and surrealist artists, including Shūzō Takiguchi and Ichirō Fukuzawa,[16] were arrested by the Tokkō on suspicion of involvement in the international communist movement. Yamamoto also came under fire and was interrogated in 1939. As a result, he was forced to cease publication of his art-poetry journal Yoru no Funsui (Night’s Fountain; 1938–39).

Activities by Japanese surrealists were strictly curtailed and censored during wartime, and the movement lost its momentum. On the other hand, experimental techniques such as photomontage and collage from New Photography movement were enthusiastically embraced by photojournalists who worked for propaganda magazines, many of which were influenced by the aesthetics of Russian Constructivism and the Bauhaus.

The experience of wartime repression made a profound impression on Yamamoto but never quashed his rebellious spirit. Yamamoto’s work was especially original around the time he was being suppressed by the military government. Said Maddox: “I think that for Yamamoto a very important period in his career was right around the time he was censored, in 1938 and 1939, when he was creating poems and texts and including them in Yoru no Funsui and producing photographs at the same time. And when the Special Higher Police interrogated him and freed him only on the condition that he wouldn’t continue publishing the journal, I think that changed him,” she said. “It really motivated him to produce work with more of an edge and that had political undertones. Everything had to be under the surface—symbolism was buried in the work. Out of that particular experience there was an explosion of really interesting work, collages, still lifes, everything he did right around that time.”[17]

Yamamoto’s images are starkly original and sophisticated, but embedded within his aesthetically refined—and often mysterious—works lurks sharp social commentary. With his nonconformist attitude and indomitable spirit, he continued his photographic and poetic experimentation throughout his lifetime.

Manfred Heiting is internationally recognized for his photography books, and his encyclopedic collection was acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 2002 and 2004. In a recent e-mail, he summed up the appeal of the two photographers’ works: “They are in complete opposition in their visual translation/manifestation of Japanese life and—for me—represent a fundamental part of the Japanese expressing their view on themselves: very traditional, observing, and with a love for his people (Hamaya), while at the same time radical and experimental, in control of emotions and imagination (Yamamoto).” He goes on: “Hamaya enhances my understanding of the country, people, and tradition, and shows me in a convincing way where my love for Japan comes from. Yamamoto appeals very much to my Bauhaus training and interest in that period of German history and my love for surrealism, photomontage, and experimentation. It is not often that one sees images like his by a Japanese artist. This is the first time Yamamoto has been recognized in a major international museum show.”[18]

Seemingly Opposite Styles Can Overlap

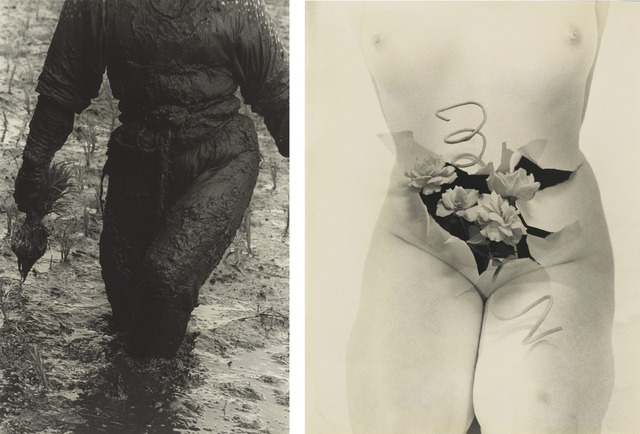

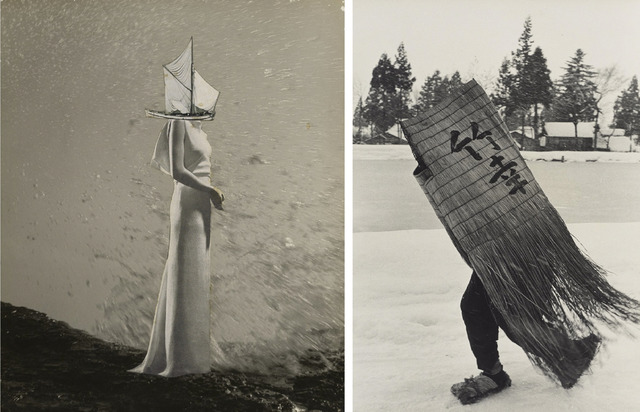

Fig. 10. (left) Woman Planting Rice, Toyama Prefecture (1955), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Fig. 11. (right) Cold Person (1956), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, from the collection of Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck.

Fig. 10. (left) Woman Planting Rice, Toyama Prefecture (1955), by Hiroshi Hamaya, gelatin silver print, © Keisuke Katano, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Fig. 11. (right) Cold Person (1956), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, from the collection of Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck.

Although their styles seem to be from opposite ends of the spectrum—Hamaya’s realism and Yamamoto’s surrealism—in fact they have the same roots. Hamaya did not delve too deeply into experimental photography, but he employed some of the same striking techniques from the New Photography movement. For example, his best-known photograph,Woman Planting Rice, Toyama Prefecture (1955), in which he has cropped out the subject’s head, he is using the same close-up technique as Yamamoto does in Cold Person (1956), the image of the torso of a naked woman with flowers protruding from her abdomen.

In 1941 Hamaya contributed to the state-run World War II propaganda magazine Front[19] (translated into fifteen languages and distributed worldwide), whose team could boast of some of the best photographers and designers. One of the powerful images he created for Front is of a Japanese tank corps rolling along an open field. The air is filled with hissing steam and the tension is palpable. Hamaya used photomontage—that is, combining several photographs into one—to make the small unit look like a massive destructive ground force.

When closely observing Hamaya’s photographs, on display chronologically at the exhibit, we notice that his later works of aerial photography, such as Delta Region, Hokkaido Prefecture, Japan (1963), seem to overlap with some of Yamamoto’s abstractions, such as Work (1959).

Fig. 12. Delta Region, Hokkaido Prefecture, Japan (1963), by Hiroshi Hamaya, cibachrome print, © Keisuke Katano, Estate of Hiroshi Hamaya, Oiso.

Fig. 12. Delta Region, Hokkaido Prefecture, Japan (1963), by Hiroshi Hamaya, cibachrome print, © Keisuke Katano, Estate of Hiroshi Hamaya, Oiso.

Jo Ann Callis, a Los Angeles-based artist and photographer whose avant-garde style of fabricated photographs has gained international recognition,[20] evaluates the technical abilities of the two men: “They are both superb technicians,” she wrote in an e-mail. “Using techniques that were available at the time, they were able to extend the boundaries of what is possible in photography.”[21]

Callis describes Hamaya and Yamamoto’s aesthetic from her viewpoint as a photographer. “I appreciate how Hamaya is obviously always aware of the formal aspects in his photography. His images reflect Japanese culture beautifully, but they are also consciously and aesthetically structured. As for Yamamoto,” she wrote, “I feel he’s a kindred spirit because my own photography has often been called surreal. Yamamoto does a lot of construction before he actually presses the shutter. This is how I’ve worked in many of my photographs. I also love his collages because it’s another way of bringing in disparate elements to twist reality and create new meaning.” She adds, “It’s an excellent example of how surrealism can provide a concrete and tightly constructed view of what exists in the artist’s and culture’s subconscious at a particular period of time.”[22]

Hamaya gained international acclaim for his documentation of the postwar Anpo protest movement, despite having maintained a pro-government stance while working at Front. Because of his affiliation with that magazine, he was able to evade censorship and keep his ethnographic project “Snow Country” going in Niigata Prefecture. He always chose innocuous and neutral subjects such as farmers, fishermen, and rural landscapes that were rather welcomed by the anti-Western government, which banned Western ideas as “dangerous thoughts.” He relied primarily on safe subjects in a nationalist context, whether or not his choices were made unconsciously.

Yamamoto, on the other hand, can be considered a political photographer just by having taken surreal photos, and he stood firm in disobedience when suffering from being deprived of his freedom of expression by the Tokkō. On a superficial level, Yamamoto developed various techniques to produce surreal and visionary works that encapsulate refined beauty, but his artworks can also be read as defiant political messages.

Yamamoto’s Unflagging Spirit and His Photographic Techniques

Because Western art-photography buffs are already to some extent familiar with Hiroshi Hamaya’s oeuvre, now I will concentrate on introducing the works of Kansuke Yamamoto, who is still relatively unknown.

Yamamoto’s rebellious spirit against the oppressive government of Japan during wartime started sometime in 1936 or 1937, before or around the outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese War, when he changed the characters of his given name. John Solt,[23] in his essay in the exhibit catalogue “Yamamoto Kansuke: Conveyer of the Impossible” (2001), noted that Yamamoto kept the sounds kan-suke but changed the two Chinese characters to “悍右,” thus altering the meaning from “Thinking Rescuer (or Enduring Rescuer)” to “Violent Right.”[24] In an interview with Solt, Yamamoto discussed his ordeal with the Tokkō. He claimed that he was subjected to questions such as “In this surreal poem of yours, what do you mean by the third line of the second stanza?” And “How does your surreal photography aid in Japan’s war effort?” Yamamoto recalled, “It was a frightening experience. I needed to evade their questions while not saying anything that the police might interpret as incriminating to me.”[25]

One single wrong step would have been enough to send him to jail for months of further interrogation or to die in a cell like other prisoners who suffered diseases and malnutrition. Yamamoto was released on the condition that he cease publication of Yoru no Funsui. Furthermore, by the end of 1939, Yamamoto became a solitary figure who dissociated himself from his photography clique. He had joined Nagoya Photo Avant-Garde in February 1939, but as soon as the group changed its name—fearing tight government censorship—to Nagoya Shashin Bunka Kyōkai (Nagoya Photography Culture Association),[26] Yamamoto severed ties to it. He described the breakup: “It was a time when we were condemned to the turmoil of war with us having no choice in the matter. A marriage of innovation and nationalism by means of photography. Is it even remotely possible? . . . That was the night when the Nagoya Photo Avant-Garde took its last breath.”[27]

Feeling a sense of stagnation in Japanese society and politics, Yamamoto expressed in his surrealist works a strong determination to fight for human dignity. He wrote in his diary, in 1938, “This one-sided and almost completely militarist nation oppresses academic and conscientious research. . . . When I think about it, I shudder with horror. This is not the answer for our nation.”[28] And in 1941 he wrote: “Artwork comes out of some disobedient spirit against ready-made things of society.”[29]

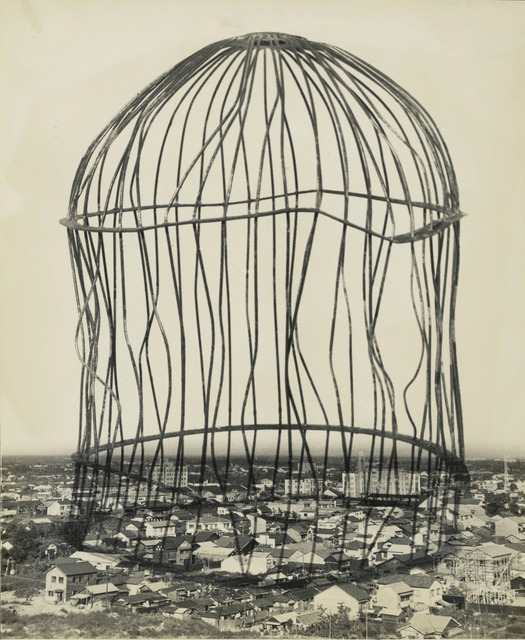

Fig. 13. Buddhist Temple’s Bird Cage (1940), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, private collection, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

Fig. 13. Buddhist Temple’s Bird Cage (1940), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, private collection, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. Fig. 14. Reminiscence (1953), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, Anne and David Ruderman.

Fig. 14. Reminiscence (1953), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, Anne and David Ruderman.

Yamamoto’s photography has some distinct features that make original, arresting images. He often incorporated ordinary daily items into his photographs. For example, Buddhist Temple’s Bird Cage (fig. 14) represents his political resistance: A birdcage can be seen as a prisonlike structure and the old-fashioned telephone within it can indicate the ability to speak freely. The temple in the title evokes Japan’s wartime military authority.

Yamamoto used these motifs as symbols, and called on the image of the cage repeatedly. In his 1953 collageReminiscence, he employs the cage motif superimposed over a city. The photo implies a memory of devastation or recalls the atomic bombing, and it may reflect his wartime experience, when the country was trapped in a gloomy political and social atmosphere. His use of the cage allows for multiple interpretations.

Fig. 15. Giving Birth to a Joke (1956), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, private collection, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

Fig. 15. Giving Birth to a Joke (1956), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, private collection, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. Fig. 16. Icarus’s Episode (1949), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, private collection, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

Fig. 16. Icarus’s Episode (1949), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, private collection, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

French surrealist works often feature powerful but disturbing imagery, occasionally with overtly grotesque mannerisms. The visual stimuli and eroticism in Yamamoto’s works are of a more subtle variety. Even critical viewers with a trained eye might miss his surreal tricks. For example, in Giving Birth to a Joke (fig. 15), two walls meet at the corner of a room and the viewer expects a vertical line going from a foot above the floor to the ceiling. There is no vertical extension of the line on the white wall, however, and one feels tricked, as if the white wall is flat or rounded while the wood at the bottom of the walls comes together at a ninety-degree angle.

In Icarus’s Episode (fig. 16), a woman seems to be wearing pointed shoes, but when you look closely at them, shrimp heads are sticking out from the toes. They are difficult to notice because the subdued shrimp heads are on a dark background. In the Greek myth, Icarus falls from the sky into the sea; in Yamamoto’s version, Icarus arrives at the sea bottom (in the form of a woman). His approach of connecting the shrimp shoes to the title is typical of his whimsical but evocative manner.

Yamamoto also showed originality in creating a non-French, surreal strand in his work when dealing with Japanese subject matter: a pile of futon mattresses installed in a field under a cloudy sky (fig. 17), numbered lockers in a public bathhouse (fig. 18), and a torn sliding paper screen door (Untitled, 1940), for example. (None of these three works was on display in the Getty exhibit.)

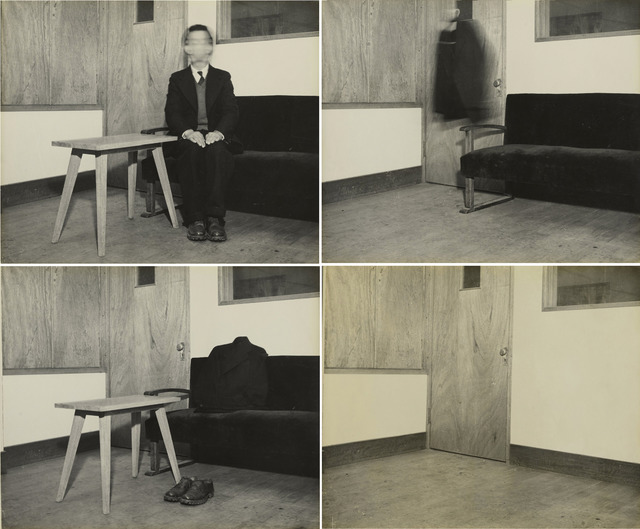

Fig. 19. My Thin-aired Room (1956), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, private collection, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

Fig. 19. My Thin-aired Room (1956), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, private collection, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

Yamamoto’s creative originality also lies in some of his series of photos, such as “My Thin-aired Room” (fig. 19) and “The Man Who Went Too Far” (1956). In the former, a sequence of four images depict a man gradually vanishing into thin air. Yamamoto’s photo story is based on Magritte’s painting L’Homme au journal” (Man with a Newspaper, 1928).

Magritte’s painting, too, consists of four parts: The first image shows a man with a newspaper; the other three are the same empty room with furniture. By means of photography, Yamamoto expresses a much thinner atmosphere than can Magritte’s heavy texture of oil painting. With a well-constructed plot, Yamamoto’s photo sequence is elegantly crafted, illustrating a refined knowledge of how to use surreal techniques.

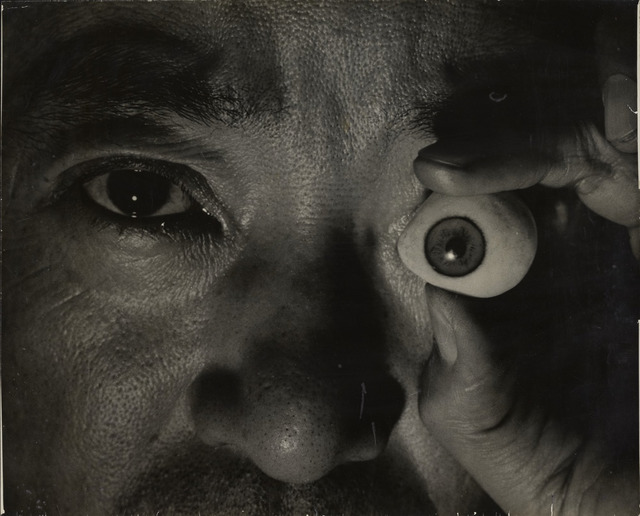

Fig. 20. Self-portrait (1940), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, private collection, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

Fig. 20. Self-portrait (1940), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, private collection, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

In her article in the exhibition catalog,[30] Amanda Maddox points out that Yamamoto’s close-up of a fig, from 1933, predates images by contemporary Japanese photographers such as Daido Moriyama, who uses the similar approach of shooting objects up close. She notes that decades after Yamamoto created Self-portrait (fig. 20), a close-up of one eye staring at the camera, with the eyelids of the other eye held open by his fingers (he’s actually holding an artificial eye over his left eye), Moriyama revisited the idea when he made Documentary 78 (’86.4 Setagaya-ku, Tokyo), in 1986. What Yamamoto was doing in the 1940s and early fifties made its way into what Japanese contemporary artists were doing in the 1960s, seventies, and even later. Yamamoto took a highly proactive role in shaping modern and contemporary Japanese photography, although the part he played has been barely acknowledged.

Yamamoto was a member of the poetry and arts coterie VOU Club (founded in 1935 by Katue Kitasono (1902–1978), himself a poet, graphic designer, and, after the war, photographer), from 1939 to 1978 (except during the Pacific War years). In its journal, called VOU, were the works of the group’s members, who contributed poems, photographs, and essays about art, music, and film. Kitasono and Yamamoto admired and respected each other’s work, but Kitasono—his senior by twelve years—occasionally offered Yamamoto tough advice. He sent Yamamoto a postcard, dated October 10, 1949, in which he wrote, “[I saw] your work at the Modern Art Exhibition. You keep holding on to a fascination with Man Ray’s ideas, and I felt greatly dissatisfied. You really need to contemplate a newer reality.”[31] After receiving this pep talk, Yamamoto shifted gears and vigorously pursued his own artistic path, and his originality blossomed.

Why Can’t Japanese Surrealism Be Original?

Japanese surrealism has long suffered from being labeled “derivative” or “imitative,” and even Japanese critics have ignored Japanese avant-garde or surreal works, considering them “fake” and inferior to Western surrealism. The Japanese have always been sensitive to Westerners’ estimations of them and, accordingly, their nation’s critics have hesitated to confer legitimacy on their surrealists until they are recognized in the West. In the exhibition catalogue Maddox writes that the relationship between French surrealists and Yamamoto was one between teachers and student, with surrealism the school.[32] Maddox mentions, too, that Yamamoto’s role was to be a translator and an interpreter who looked to surrealists abroad in order to produce works that expanded the visual lexicon of the movement in Japan.

Yamamoto was curious and interested in learning more about works by Magritte and Man Ray, among others, to understand more fully surrealism’s various dimensions, but he took no interest in slavishly aping others. Rather, he was intent on developing his own viewpoint within the genre.

As a point of comparison, let us briefly consider the case of Balthus (1908–2001), who spent the year 1926 traveling in Italy, where he made copies and sketches of frescoes by Piero della Francesca and other Renaissance masters. He was self-taught by copying the great painters of antiquity, such as the Renaissance maestro Piero and the French Baroque painter Nicolas Poussin. He was also struck by the nineteenth-century realists Gustave Courbet and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Although Balthus was heavily influenced by these artists, his creations were his own, starkly original works, and no one faults him for his debt to the past.

Yamamoto went through a similar process of self-education, in absorbing surrealist forms and achieving mastery of methods that would be important to his own work. When Balthus copied works by his European old masters, no one took him to task; when Yamamoto did the same thing by importing and referring to Western surrealism, suddenly he was labeled “derivative.” When a certain art form originates in Western Europe, is it then (subconsciously) assumed by Westerners to be their property?

In this regard, I remember an episode at a workshop at Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo, in 2010. One of the Japanese participants said, “I think the works of Japanese artists such as Harue Koga are imitations of French surrealism.” John Solt responded, “I think surrealism is a method, similar to the camera being a tool, and it is available to anyone, regardless of his culture of origin. For people to assert that surrealism is exclusively French and anyone else can achieve only a form of imitation is a chauvinistic concept. The French don’t own surrealism any more than they own photography because Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre invented the daguerreotype. What matters is what is expressed using the surrealist method.”

Along similar lines Majella Munro, in her effort to flatten the hierarchy of “core (France)-periphery (Japan)” and evoke a space in which participants could contribute on equal footing, introduces the idea of an “imagined community.”[33]

Not only did Yamamoto introduce his own powerful expression of surrealist aesthetics to a Japanese audience, but he also developed his own photographic and collage styles—occasionally composing images with positive and negative fragments—with a flair that has stood the test of time. His innovative and unconventional work with experimental strands contains eroticism, humor, and social and political commentary, and he never fails to endow the works with sophistication and elegance.

Fig. 21. Untitled (body floating over sand) (1938), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, Nagoya City Art Museum.

Fig. 21. Untitled (body floating over sand) (1938), by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, Nagoya City Art Museum.Photographers without Books Remain Nameless

Despite continually having created first-rate works, Yamamoto is yet to be held in high regard by the Japanese photo establishment. One of the reasons he remains relatively unknown is that he lacked the ambition to make a name for himself. He turned his back on commercial success partly because of his wealthy family background, but especially because of his tireless passion and efforts in pursuing nonconformist avant-garde forms of expression. His work was featured in outlets such as photo and poetry magazines and group exhibitions, especially as a member of the cutting-edge avant-garde magazine VOU, to which he regularly contributed his poetry and artwork. The thirty-one VOU group exhibitions provided opportunities to present his work publicly and connected it to the avant-garde Tokyo and regional art scenes.

Yamamoto also formed the photography group VIVI, in Nagoya in 1947, and that forum enabled him to stage local exhibitions. His own activity, however, was well known only within a small circle of artists and associates. Surprisingly, the Getty and Tokyo Station Gallery exhibition catalogues—both posthumous—are the only photo books of his work ever published.

Yamamoto “missed the boat” in the 1960s and beyond because he had no photo book. He sent a portfolio of his work to the up-and-coming photographer Shomei Tomatsu (1930–2012); the younger photographer dampened his enthusiasm by responding that a book of such photos would never sell.[34]

Manfred Heiting, the foremost collector of photography books, believes Yamamoto’s lack of recognition is related to the fact that no photo books or portfolios were published during his lifetime or even after his death. According to Heiting, “As far as I have learned, photo books have been the traditional medium in Japan for photographers and related artists. I can only speculate that Yamamoto was not at the center of the photography and contemporary art scene in the 1950s–1970s as were Hamaya, Ihei [Kimura], [Yoshio] Watanabe, Moriyama, Tomatsu, [Kishin] Shinoyama, [Nobuyoshi] Araki, Ikko [Narahara], [Shoji] Ueda, Hosoe, and all the other great photographers who have been publishing books early on or those who were rediscovered.” He goes on: “The ‘collecting’ of photographs has much more of a tradition in the history of European and American art, and in Japan it is a very different situation because of tradition, education—and lack of space. Only in the 1970s did the interest in photographic prints become more relevant to the Japanese themselves, and that occurred because of the rise of the market. Yamamoto did not have that ‘connection,’ but a Japanese museum, publisher or educator should not be dissuaded by that any longer.”[35]

The Pacific Rim Divide

The Getty’s “Japan Modern Divide” enjoyed a huge success on the American side of the Pacific Rim and took a landmark step toward visibility in the international mainstream art scene, while, ironically, the Japanese photographic establishment has been limping behind. Considering that (1) the Getty Museum is the richest in the world; (2) this is the first time Japanese photographers have been featured at the Getty; (3) and three hundred and sixty thousand people have viewed the exhibit, it has received relatively scant notice in the Japanese media. There have been two citations as of this writing—one in the Japanese edition of Vogue (February 2013) and the other in the Mainichi Shimbun (August 19, 2013), with a passing notation (“Oh by the way, there’s a Japanese exhibit at the Getty”) in an article titled “Salad Bowl in the USA,” mostly about the Union Bank in Los Angeles. The Mainichi article is emblematic of the current state of the Japanese media’s inability to recognize newsworthiness with any discernment. Even when they don’t ignore, they trivialize. In today’s age of simultaneity and instantaneity, the relative ignoring of the exhibit deserves closer examination.

As a point of comparison, a much smaller but also significant exhibit at the Getty that featured the Rubens depiction of the first Korean portrayed in a Western oil painting[36] was attended by not only the Korean community in Los Angeles but also apparently even by Korean President Park Geun-hye, who was accompanied by a retinue of official cars and her entourage to see the two-room exhibition.

It is wonderful that a head of state—one of the busiest in the world—cared enough about her country’s culture to take time out to enjoy the exhibit. Not only have Japanese political figures not shown up at “Japan’s Modern Divide,” but the media have also been a community asleep at the wheel.

Trying to understand possible reasons behind the neglect, I posed that question to Yusaku Hosoya, head of Yagisha, an independent photo-book publishing firm based in Tokyo, who also writes for photo and camera magazines. Hosoya believes that the Japanese media—including newspapers and magazines—are appeasing readers rather than informing and educating them. “The Japanese media are losing their function . . . and shrinking to accommodate the taste of the audience,” he told me. “The traditional flow of information from mass media to the public has been altered and now it is the public’s turn to control the media by disseminating information on its own.”[37]

Incidentally, when a journalist friend contacted the Japan Times, an English-language daily newspaper, and offered to write an article about the Hamaya-Yamamoto show at the Getty, the offer was declined because the paper is interested only in domestic art events. It seems that even the Japan Times has tunnel vision. Perhaps the inability of the Japanese media to disseminate high-quality, cutting-edge information is helping to spur the demise of print media.

Japan has a long tradition, since the late nineteenth century, of overseas collectors and critics discovering and evaluating Japanese art. Tenshin Okakura aided Ernest Fenollosa in educating both Americans and Japanese about the value of Japanese classical art. Brahmin Bostonians brought back treasures from Japan (and China). Examples are ukiyo-e,Raymond Bushell’s scholarship on netsuke, and Joe Price’s discovery of Itō Jakuchū. If this penchant for Westerners occasionally to discover Japanese artists persists, perhaps Hiroshi Hamaya and especially Kansuke Yamamoto will be better appreciated in their own country.

I asked the opinion of one of the few people to have seen all three Kansuke Yamamoto exhibits,[38] Tetsuya Taguchi, dean of the Faculty of Culture and Information Science at Doshisha University, in Kyoto. Taguchi commented on the Getty show: “I was lucky enough to be given another opportunity to witness Yamamoto’s works at one of the major museums in North America. What struck me was that US viewers seemed to be enjoying this Japanese avant-garde artist’s works with a relish as if they were cosmopolitan, contemporary photos.”[39]

In Taguchi’s estimation, Kansuke Yamamoto’s work is still ahead of the curve. “It is next to impossible for me to imagine how Yamamoto was able to maintain his artistic credo under the fascist regime in the early 1930s through the mid-1940s,” he said. “A lot of Japanese, including myself, are now starting to understand what Yamamoto was attempting. Liberated minds and imaginative eyes can see in his subtly manipulated photos a drama, perhaps even focusing on the movement of materials on a molecular level. In our postmodern era, we communicate by images at the expense of language. Who could think of that when Yamamoto was most active?”

Conclusion

The 2001 solo show at the Tokyo Station Gallery was favorably mentioned and reviewed by members of the media such as the Japanese TV broadcaster NHK, and attracted many visitors. After the show, however, neither art galleries nor publishers of art books picked up his work, and consequently the momentum fizzled. The next cycle was twelve years later, when the Getty curators showed his work for the first time in the West—a breakthrough discovery that is already percolating within the worldwide photography community.

One reason for the Japanese neglect may be that photography is a relatively new art form and avid attention to it has been a relatively recent phenomenon. Crucially, there has been in Japan no art market for fine-art photography or contemporary art. The contemporary-art market has gained some energy in the past five years, but the market in Japan is still fairly small. This does not mean that the quality of Japanese art photography is poor or even mediocre. Private collectors and major art museums in the United States have quietly been purchasing Japanese photography as an “undervalued stock” when compared to the works produced around the same time by established Western photographers and to paintings by European masters.

The Getty’s department of photography purchased and also received donations of photographs from Japan, China, and Korea. In recent years the focus of its collection is turning more toward Asia. Notes Judith Keller: “In China and Korea, photography is a relatively new field. Japan, however, has a very strong and old tradition and history of great photography being produced. Asia is an area that we are learning about and that we want to give more attention to.”[40]

Scant interest has been paid to Japan’s prewar and postwar avant-garde art in the West. The recent acclamation surrounding the shows of the postwar groups Mono-ha and Gutai, however, as well as of the Hamaya/Yamamoto exhibit at the Getty seems to have created a critical mass, perhaps even a “boom,” in the subfield of Japanese art within the present-day American art scene. A number of great Japanese surrealist and avant-garde artists are becoming recognized and reevaluated in both Japan and the United States, sometimes the latter outpacing the former.

The Getty Museum’s “Japan Modern Divide” may serve as a new divide, further defining the relevance of Hamaya and Yamamoto to Japanese photography, the importing of an export.

Kansuke Yamamoto was questioned in 1939 by the Thought Police and asked how his surrealist photographs were aiding the country. He was stumped for an answer and feared for his safety. Now he could reply that his avant-garde art plays the role of a cultural bridge on the US side of the Pacific Rim whereas the Japanese side only half-heartedly takes notice.

Eiko Aoki is a freelance journalist and researcher covering Pacific Rim arts and specializing in photography. She was a translator for the sports section of the Asahi Shimbun (a Japanese-language daily newspaper). Later she became an art and culture writer for the Japanese edition of the International Herald Tribune (now the New York Times). Her bilingual work has appeared in Kyoto Journal, LACMA, Sei’en, and elsewhere. She lives in Kyoto, where she co-edits the Kenneth Rexroth Reader (in Japanese) and writes her popular blog, http://artthrob.exblog.jp.

Notes

- The Guggenheim Museum mounted the major exhibition “Gutai: Splendid Playground” (February 15–May 8, 2013) and the Museum of Modern Art presented “Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde” (November 18, 2012–February 25, 2013). The Los Angeles–based gallery Blum & Poe made a quick move to introduce major works of Mono-ha in “Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha” (February 25–April 14, 2012), which traveled to the Gladstone Gallery, New York City (June 22–August 3, 2012).

- The author talked with Judith Keller, senior curator of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s department of photographs, and Amanda Maddox, assistant curator of the same department, in the exhibition galleries on June 11, 2013. The transcription of the interview is available in the fall 2013 issue of Kyoto Journal, a fee-based online magazine.

- Shūzō Takiguchi (1903–1979) was an influential poet, art critic, and artist who was instrumental in introducing surrealism to Japan in the 1920s through his writings and translations. In 1937 he organized the seminal surrealist exhibition in Japan with the support of European surrealists. In 1940, Takiguchi—quicker than any Westerner—wrote the first monograph on Joan Miró. Takiguchi’s main artworks are the series of decalcomania he created around 1960.

- Front was the state-run World War II propaganda magazine published by Tōhō-sha, which was established in 1941. The magazine lasted for only ten issues, however, from 1942 to 1945. The magazine was produced with the highest-quality paper, ink, and equipment. Front artists often adopted photomontage to manipulate size, scale, and perspective to make the military force look as powerful as possible.

- Jo Ann Callis: Woman Twirling is the catalogue of an exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum from March 31 to August 9, 2009. The volume, comprising fifty-five color and fifteen black-and-white works that range from 1974 to 2005, constitutes the first book-length treatment of Callis’s work since 1989. http://shop.getty.edu/products/jo-ann-callis-978-0892369560

- John Solt is a poet, translator, and independent scholar. He is an authority on Kitasono Katue’s artworks and poetry and wrote the definitive critical biography of him, Shredding the Tapestry of Meaning (the Japanese translation was published in 2010). In 2001, Solt co-curated the exhibition “Yamamoto Kansuke: Conveyor of the Impossible” at Tokyo Station Gallery and wrote an article for the catalogue, “Perception, Misperception, Nonperception.”http://209.172.130.121/solt-kansuke2.html

- Majella Munro, Communicating Vessels: The Surrealist Movement in Japan, 1925–70 (UK: Enzo 2012), 20. Munro credits Benedict Anderson’s work on nationalism for the insight. http://enzoarts.com/communicating-vessels/

- “Looking East: Rubens’s Encounter with Asia” at the Getty Museum (March 5–June 9, 2013).http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/looking_east/

- (1) The 1988 solo show “Yamamoto Kansuke” was held at Imagination Market Q & P in Ginza, Tokyo, April 11–23. (2) The 2001 solo show “Yamamoto Kansuke: Conveyor of the Impossible” was held at Tokyo Station Gallery August 22–September 24. (3) The Getty Museum’s 2013 exhibition “Japan’s Modern Divide.”

No comments:

Post a Comment